Exhibitions

2021-2 MOMAT Collection

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

The collection exhibition from October 5, 2021 to February 13, 2022

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection! In this exhibition, we introduce currents in Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day, along with a variety of works from other countries.

Room 1 on the 4th floor, in which viewers can enjoy an assortment of masterworks selected from the museum collection, has been recast as “Highlights, Newly Indexed,” featuring a lineup of outstanding art as always, but arranged with a somewhat different approach. Room 3 presents works by painters associated with the influential journal Shirakaba, in which Yanagi Muneyoshi (Soetsu), founder of the Mingei movement, was a key participant, in conjunction with the exhibition 100 Years of Mingei: The Folk Crafts Movement on view on the 1st floor from October 26. In Rooms 7 and 8 on the 3rd floor, we focus on postwar artists whose practice straddles boundaries between painting and graphic design. Meanwhile, in Room 11 on the 2nd floor, we are pleased to present a new edition of the video A Pottery Produced by Five Potters at Once (Silent Attempt) directed by Tanaka Koki (2013), with Japanese sign language and captions. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo produced it in 2021 in an endeavor to broaden opportunities for art appreciation, and it is viewable for free online for a period of one year.

Once again this term, we invite you to enjoy a wide range of selections from the MOMAT Collection at your leisure.

translated by Christopher Stephens

Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 15 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as Important Cultural Properties. These include nine Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Wada Sanzo, South Wind, 1907

- Yorozu Tetsugoro, Nude Beauty, 1912

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915

- Please visit the Important Cultural Property section Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

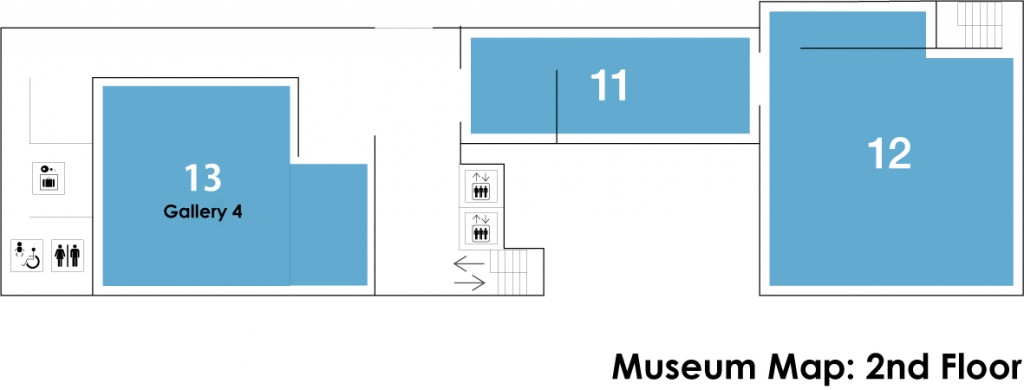

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F (Fourth floor)

Room 1 Highlights * This section presents a consolidation of splendid works from the collection, with a focus on Master Pieces.

Room 2– 5 1900s-1940s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

A Room With A View

Reference Corner is currently out of service.

Room 1 Highlights, Newly Indexed

Room 1 is where we always present some of the museum’s most prized masterworks, but this term we are taking a somewhat different approach. We aim to make the room an introductory microcosm of our collection, keeping the following two criteria in mind when selecting works. One is to have the room serve as an index for the entirety of the MOMAT Collection selections exhibited this term. Rooms 2 through 12 feature works organized with a specific theme for each room. As a preview, several works related to these themes are featured in Room 1. At the end of the commentary we have added a guide to related rooms, so viewers can go on to see the rooms that interest them for further in-depth viewing.

The other criterion is to showcase the breadth of our entire collection. The oldest works in our collection are photographs from the 1840s, and the newest are Western paintings (entrusted to the museum) and prints from 2020. In Room 1, works produced over more than 130 years from the 1880s to 2019 are on view, with Nihon-ga (modern Japanese-style paintings) in glass cases in increments of about 25 years, and framed works on the dark blue walls in increments of about 15 years. Recently, our contemporary art holdings have been progressively enriched as well.

Room 2 East and West, Collision and Fusion

The room before this one contains Harada Naojiro’s Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon. Its mode of Japanese Western-style painting, using a Western technique (oil painting) to depict an East Asian Buddhist subject, may seem incongruous today, but it is precisely this incongruity that conveys the first stirrings of an important new movement. Amid the wave of Westernization swiftly sweeping the nation since the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate in the mid-19th century, artists sought to forge an intrinsically Japanese painting style while incorporating techniques from the West. This can be called the dawn of modernism in Japanese art.

During an era of conflicting currents of European influence and Japanese nativist ideals, the Bunten exhibition (sponsored by the Ministry of Education) was established in 1907, modeled on the official salons of France. The Bunten, which established the categories of Nihon-ga (modern Japanese-stylenpainting), Yo-ga (Japanese Western-style painting), and sculpture, stabilized the development of styles and formats in Japanese art. With the exception of the works of Kume Keiichiro, everything in this room was originally exhibited at the Bunten. In Wada Sanzo’s idealized (Western-style) rendering of the human figure, the realism of Kume’s (Western-style) depiction of color in shadows, Kosugi Misei (Houan)’s (East Asian-style) curtailment of oiliness of the painting surface, and Wada Eisaku’s serene (East Asian-style) composition featuring stark contrast between foreground and the distant background, we see the process of Japanese and Western styles clashing and then colliding, blending, and finally harmoniously fusing.

Room 3 Irrepressible Freiheit: Shirakaba and Youth

In this section, in conjunction with the exhibition 100 Years of Mingei on view on the 1st floor from October 26, we primarily present works related to the Shirakaba group, which was closely affiliated with the Mingei (folk crafts) movement. The literary magazine Shirakaba, launched in 1910 by Yanagi Muneyoshi (Soetsu) and others, contained forward-looking discourse that encouraged originality, and was an inspiration to young artists. Takamura Kotaro’s treatise A Green Sun, published the same year as Shirakaba’s establishment, vividly conveyed the mood of the day: “I seek absolute Freiheit [German for ‘freedom’] in the art world.” Even if someone paints a green sun, you can’t say it is wrong. This was not only a declaration of reverence for individuality, but also an affirmation of introspection (as the sun indeed glows green when the eyes are closed), and a paean to life itself.

The sculptures of Ogiwara Morie, which undulate as if imbued with the romantic yearnings of their creator, and the intense palette of Yorozu Tetsugoro, a provocateur to the previous generation, can be said to embody this era. Shirakaba actively presented modern art from the West in its pages, and had a direct, formative influence on the styles of its day. The viewer will notice that styles have changed dramatically from the mildness of the previous room. Cezanne’s stripped-down deconstruction of landscape, Van Gogh’s passionate brushwork, and Rodin’s sculptural rendering of muscular tension are all currents flowing through these works.

Room 4 Life Carved in Wood: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints

In the late Meiji (1868–1912) and Taisho (1912–1926) eras, amid increasingly modern perceptions of the self and originality in art stimulated by the introduction of new artistic movements from the West, there was rising momentum toward establishing hanga (Japanese printmaking) as not merely a duplicative technology but a full-fledged art form in its own right. In the context of advances in printing technologies and a backlash against the division of labor in ukiyo-e printmaking, the practice of sosaku hanga (creative prints) was championed. This entailed a single artist completing every step of the process, from the original drawing through the printing of the finished product, and the Nihon Sosaku Hanga Kyokai (Japan Creative Print Association) was formed in 1918. Woodblock printmaking, involving the direct carving of wood blocks, played a central role. In this we can see the spirit of emphasis on hand-crafting crucial to Mingei (folk crafts). Munakata Shiko was a woodblock printmaker closely involved in the Mingei movement. While early sosaku hanga tended to draw directly on the artist’s inner life and emotions, there was a subsequent move toward exploration of the intrinsic properties of the woodcut medium, including simple forms, stark black and white contrasts, and forceful lines, and a wide range of highly original works were produced.

Room 5 Under Paris Skies

A popular chanson by Hubert Giraud contains the lyrics “Stranger beware, there’s love in the air, under Paris skies…” but according to Henri Rousseau, there was also a goddess in the Paris skies who led artists onward. Beckoned by the goddess’s bugle, artists gathered at galleries with their works in hand. Open salons where artists could exhibit their work without undergoing screenings meant respect for the unique character of each artist. This mentality came to influence Japanese artists around 1910, and an enormous number of Japanese artists, seeking the world capital of art, set sail for Paris, especially during the interwar period. They painted Paris scenes from wide-ranging perspectives, but when we look over their works in the MOMAT collection, we see fewer tourist attractions and spectacular views than works that shed light on the overlooked and neglected: back streets, lonely cafés, blue-collar workers. For those coming to live in Paris as foreigners from a faraway land, these may have seemed like quite sympathetic subjects.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s

From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 A Turbulent Era

This room brings together diverse depictions of the human figure dating from 1937, when the Second Sino-Japanese War began, through 1949 after the end of World War II. Strictly speaking, AI-MITSU’s Landscape with an Eye may not be a human figure, but the eye in this painting certainly makes an impression. Whose is this disembodied eye, and what is it seeing? As you move through the room, you may notice its similarity to the urgent gaze of Aso Saburo’s Self-Portrait. So, could the eye in Landscape with an Eye be AI-MITSU’s own? However, a look at his own Self-Portrait painted just before going off to war reveals eyes that make a completely different impression.

These painters seem to have captured on canvas the presences of irreplaceable people close to them during these turbulent years. Aso repeatedly portrayed his wife and young daughter, and Wakita Kazu’s Children in the Studio depicts his two sons. When he painted it, he was just about to depart for the Philippines on an army commission to produce war record paintings. What was going through his mind as he worked on this painting?

Room 7 Fine Art and Advertising Art, Part I

Japan Advertising Art Club (Nissenbi) was founded in 1951 as the nation’s first professional organization of graphic designers. Reading texts written by the association’s members at the time of its establishment, one does not encounter the now-common loan word dezain (design), but rather the term senden bijutsu (advertising art). These writings convey the sense that they were dissatisfied with the lack of independence characterizing advertising art as a field, and sought to place value on artistic quality and authorship.

Some members of Nissenbi were also active in fine art circles. For example, Hayakawa Yoshio and Yamashiro Ryuichi were members of the Democrato Artists Association, led by EI-KYU, and similarities in their styles can be seen. Yamaguchi Masaki, a designer for Yamaha pianos and a Sankyo camera, also exhibited abstract paintings. It is apparent that the boundary between art and design was not as clearly defined as it is today.

Room 8 Fine Art and Advertising Art, Part II

The process of abstraction in art and design isolates and gives shape to certain elements and properties of objects. Artists and designers communicate with viewers by skillfully modulating the degree of abstraction in their works. For example, in advertising posters, an appropriate degree of abstraction may make it easier to communicate information. In painting and sculpture, sometimes avoiding realistic depictions more effectively conveys sensory images.

In the 1950s and 1960s, abstraction often featured loose, curving forms. These organic morphologies, somehow reminiscent of living things, are described as biomorphic, and their influence was also seen in furniture design.

In this section, please enjoy comparing the paintings and sculptures of Sugai Kumi, Koiso Ryohei, and Kitadai Shozo with posters these artists designed. Koiso belonged to the association Shinseisaku, and Kitadai was a member Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop). Works by some of their associates are also exhibited.

Room 9 Ishimoto Yasuhiro: Leaves, Cans, Clouds and Snow Steps

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the photographer Ishimoto Yasuhiro’s birth, we present a special exhibit of four series dealing with ephemeral things, which he produced between the late 1980s and the mid-90s.

The series began with images of rain-washed, decaying fallen leaves on the pavement, and a leaflet for a solo exhibition featuring two of them, Clouds and Snow Steps, quoted a passage from the medieval Japanese text Hojoki (The Ten-Foot Square Hut): “The flow of the river is ceaseless and its water is never the same. The bubbles that float in the pools, now vanishing, now forming, are not of long duration: so in the world are man and his dwellings.”

These series take the passage of time as their subject, and were later collected with several other series into a photobook, Moment (published in 2004).

Ishimoto was known as a true modernist who studied at the IIT Institute of Design (known as the New Bauhaus) in Chicago, but in these series he awakened to a quintessentially Japanese sense of time as a looping spiral, and is said to have realized this Japanese sensibility was alive and well within him.

Room 10 Seeing Sounds (First half: October 5–December 5, 2021)

(Exhibit Dates: October 5–December 5, 2021)

When we look at a picture, our minds rely on information obtained through the eyes, such as color, shape, and composition. However, his does not mean the visual arts are wholly unrelated to sound. On the contrary, expressing invisible sound in visible form has long been a vital concern for many painters.

Wassily Kandinsky and Hans Richter applied the structure of music – in which melody and rhythm are generated simply by combining sounds – to painting. Rather than using colors and forms to represent something from the world around, they sought to create a new mode of expression in which colors and forms themselves purely resonate on the canvas.

In the room farthest in the rear we present works, primarily Japanese paintings and prints, that seem to convey sounds. The artist’s accomplishments lie in their ability to render things invisible to the eye, dealing not only with musical themes but also with random noise occurring in the course of everyday life and the sounds of animals. Listen: can you hear a symphony of sounds in the quiet gallery? Relax your eyes and ears, and savor sounds that only you can hear.

Room 10 The Mecha Aesthetic (Second half: December 7, 2021–February 13, 2022)

(Exhibit Dates: December 7, 2021–February 13, 2022)

The 1920s and 30s was an era of rapid modernization, when urban culture flourished and a new appreciation of the beauty of machines was growing. In Leaning Woman, Yorozu Tetsugoro dismantled the human body into components, as if it were a machine, and reconstituted it by combining them with geometric shapes. He was clearly influenced by Cubism, pioneered by Picasso and Braque in France, but the work also conveys a particular vision that equates people and machines.

Meanwhile, what was occurring in the world of Nihon-ga (modern Japanese-style painting) at the time? Telescopes and cameras were among the motifs that heralded the arrival of a new era, and the hardness and heft of metal contrasted with and complemented the pale, youthful skin and suppleness of female figures. After World War II, members of the Pan-Real Art Association such as Mikami Makoto and Hoshino Shingo pursued Nihon-ga that grappled with reality, not in the sense of realistic painting, but in the sense of depicting the truths of present-day society. Their works present vistas of the imagination in which plants and animals appear barely suffused with life while machines seem to possess a will of their own, and the biological and mechanical are fused.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Gallery 4 presents 100 Years of Mingei, a Folk Crafts Movement during this period.

* A space of about 250 square meters. This gallery offers cutting-edge thematic exhibitions from the Museum Collection, and special exhibitions featuring photographs or design.

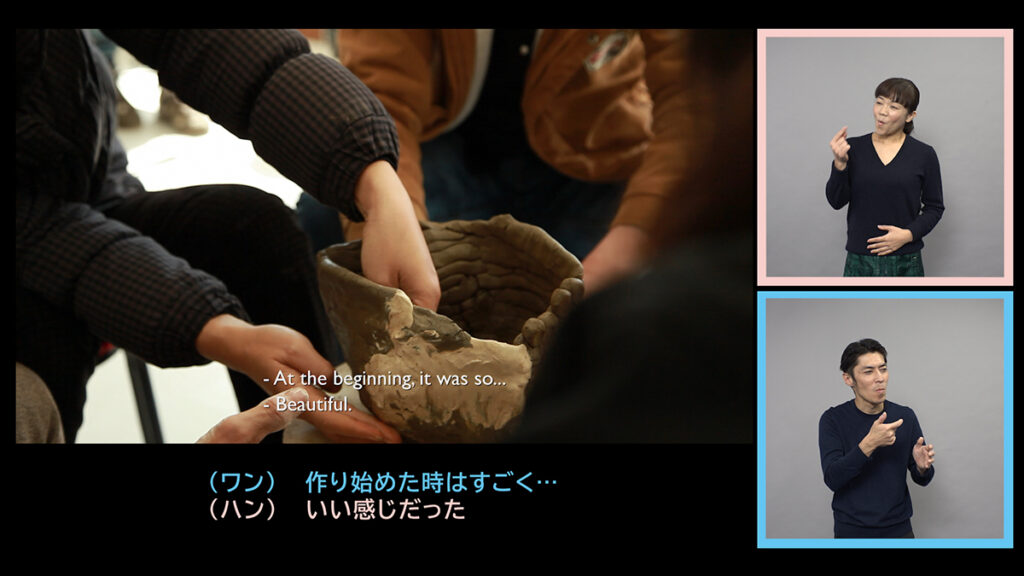

Room 11 Working Together

In recent years, video works have been shown more frequently at museums, but few are accompanied by captioning or sign-language videos, and for the deaf and hard of hearing, there are significant obstacles to watching video works. In 2021, the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo secured the cooperation of the artist Tanaka Koki in producing a new edition of his video A Pottery Produced by Five Potters at Once (Silent Attempt) (2013), part of the museum’s collection, with Japanese sign language and subtitles, in an endeavor to broaden opportunities for art appreciation. The theme of this work is “collaboration” among people of different origins, circumstances, genders, and mentalities, and this edition with sign language and captions was also a collaboration in which people in different positions – the artist, deaf individuals, and museum staff – came together to create a single work. At times it can be difficult for multiple people to share a single goal, but this process is also a first step toward understanding other people from other walks of life.

In this room we present works related to collaboration, alongside this new edition of the video intended for appreciation by a wider audience.

Room 12 Territory of the Modern(ism)

In this room we present works that, with one exception, date from the 1960s through the late 1980s. The word “modern” in The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, which opened in 1952, has been translated from English and other European languages into Japanese in different ways at different times, with varying nuances such as “of the modern era,” “contemporary,” “recent,” and “current.” The most common Japanese word for “modern” is kindai, also in this museum’s name, and during the museum-building boom of the 1970s and 1980s, museums with this appellation were constructed all throughout Japan. Both the construction boom and the craze(?) for giving museums names including “modern” came to a close around the end of the 1980s. This was surely related to the collapse of the economic bubble, and to the extensive discourse on postmodernism during the 1980s.

“Has the modern era already ended?” “Where is the line between modern and contemporary?” “Do museum names even matter?” These are serious questions facing “museums of modern art,” which have continued handling art of the present day since the 1990s. With the above concerns in mind, we decided to make the end of the 1980s, which marked a turning point for the “modern,” the cutoff point for this exhibit, while also hoping to share these concerns with you, the viewer.

About the Exhibition

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

October 5, 2021–February 13, 2022

- Time

-

10:00-17:00 (Fridays and Saturdays open until 20:00)

*Last admission : 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

Mondays (except January 10, 2022), from December 27 to January 1, 2022 and January 11, 2022

- Ticket

-

Advance ticket is recommended to avoid lines forming at the entrance.

Online purchase: 【e-tix】

Tickets can be purchased on site at the ticket counters, subject to their availability. - Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)

*The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

*Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

*Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

*Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID. - Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 17:00 on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Organized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo