展覧

2014-6 MOMAT Collection

Date

-Location

Art Museum Collection Gallery

Highlights

Important Cultural Property

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection! This edition of the exhibit places a special emphasis on two points: 1. a group of masterpieces that are sure to delight any fan of Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting), and 2. a series of works related to the Kataoka Tamako exhibition (April 7–May 17) on the first floor.

Room 1 (4th floor): In the Highlight corner, we present Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring(Important Cultural Property) as a poetic celebration of spring. The luxuriant painting, Tsuchida Bakusen’s Maiko in a Garden, familiar to many from the postage stamp, can also be enjoyed here. And next door in Room 2, be sure to have a look at Kaburaki Kiyokata’s Portrait of Sanyutei Encho (Important Cultural Property).

Room 10 (3rd floor): In the Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) section, we feature works by female artists. Here you’ll find a lineup that includes Uemura Shoen’s Mother and Child(Important Cultural Property), Ogura Yuki’s Bathing Women, and After Bathing. Can you find any similarities between the women’s works?

Room 11 (2nd floor): Kataoka Tamako once said, “Paintings have to be bad.” With this sentiment in mind, we present a group of works by artists such as Kusama Yayoi and Jean Dubuffet that are so unique that they transcend any conscious effort to look good.

Important Cultural Properties on display

1890 (Long time loan;coll. Gokokuji Temple)

The collection at the main building of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo now has thirteen pieces that are designated as Important Cultural Properties by the Japanese government, comprising eight Japanese-style paintings, four oil paintings and one sculpture.

The following Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890 (Long time loan;coll. Gokokuji Temple)

- Yorozu Tetsugoro, Nude Beauty, 1912

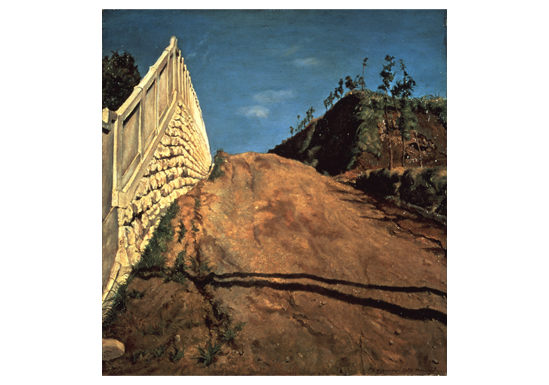

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915

- Kawai Gyokudo, Parting Spring , 1916

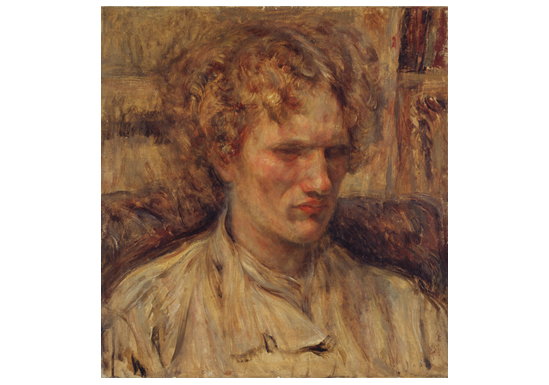

- Nakamura Tsune, Portrait of Vasilii Yaroshenko , 1920

- Kaburaki Kiyokata, Portrait of San’yutei Encho , 1930

- Uemura Shoen , Mother and Child , 1934

Please visit the Important Cultural Property section Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

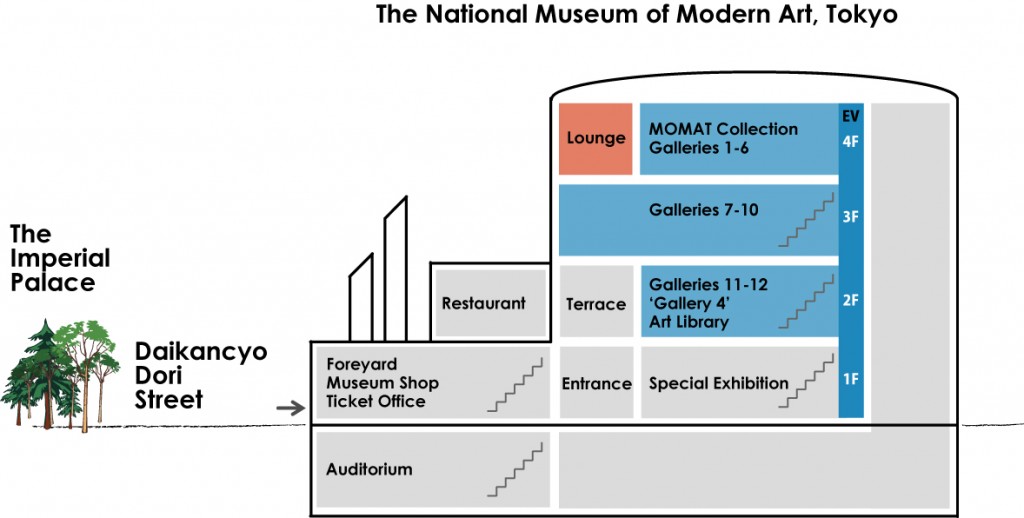

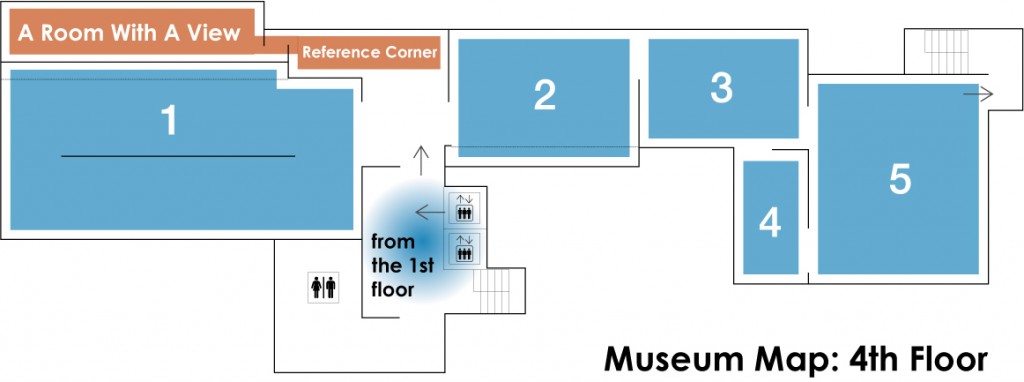

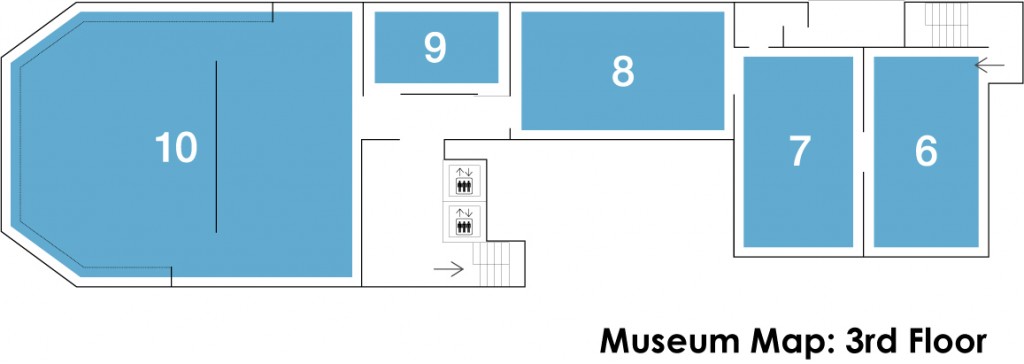

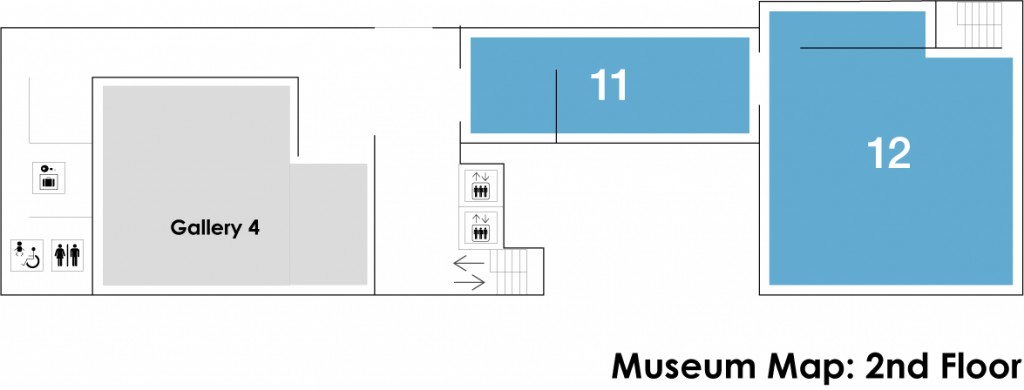

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section below make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation A Room With a View is on the fourth floor.

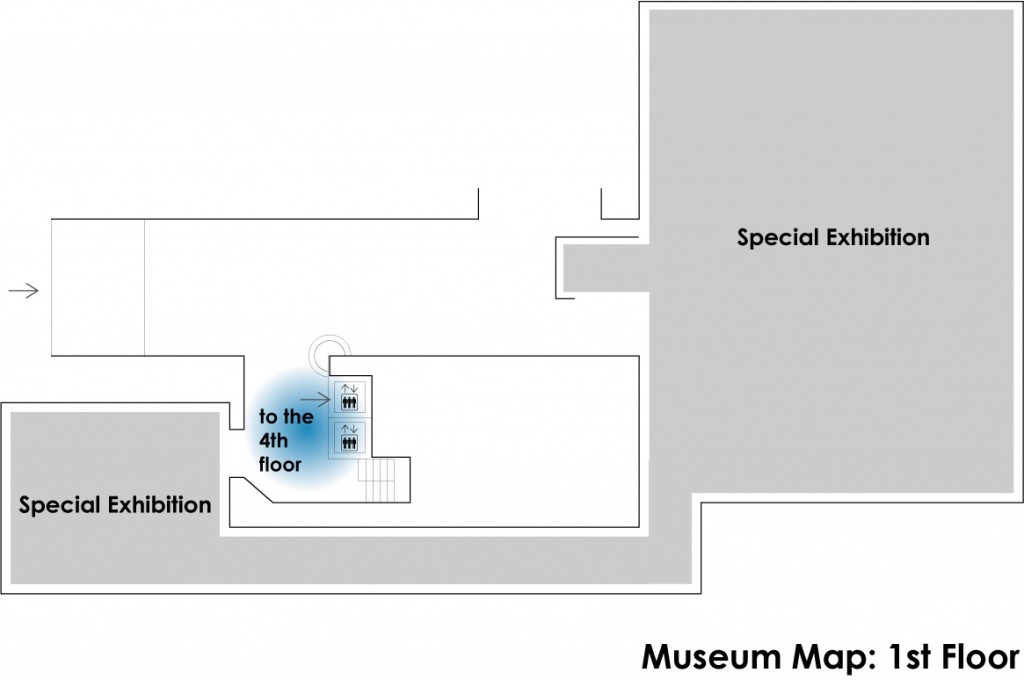

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

Room 1 Highlights * This section presents a consolidation of splendid works from the collection, with a focus on Master Pieces.

Room 2– 5 1900s-1940s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

A Room With A View

Reference Corner

Room 1 Highlight

Over 200 works are lined up in this 3,000-square-meter space — these extravagant conditions are the selling point of the MOMAT Collection. But in recent years, we have received an increasing number of comments like, “They’re so many things here, I’m not sure what to see!” and “All I want to do is have a quick look at the famous works in a short period of time!” Thus, in conjunction with the gallery renovation that was completed in 2012, we have created this “Highlights” corner to allow visitors to enjoy a consolidation of splendid works from the collection, with a focus on Important Cultural Properties. For the walls, we have selected navy blue to make the works stand out more beautifully. And to eliminate the glare of glass cases, we have opted for a mat black for the floor to help viewers concentrate on the displays.

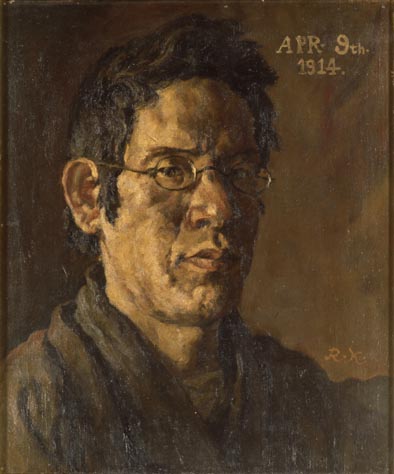

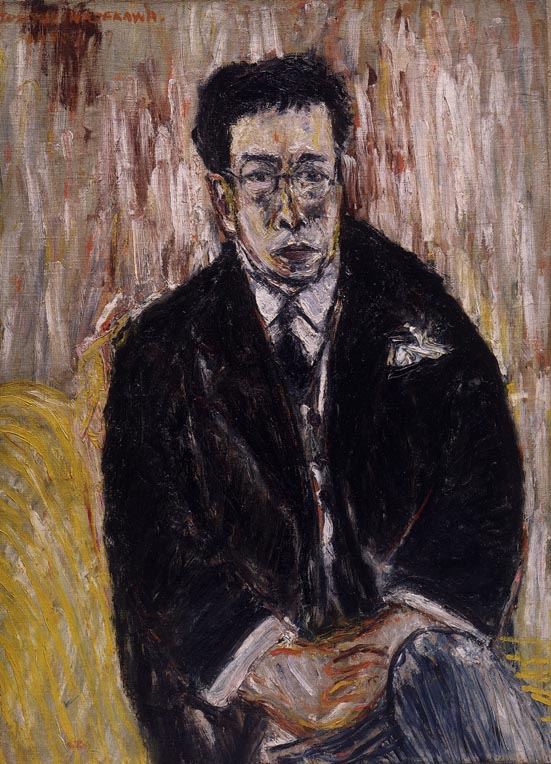

In this exhibit, we present Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring, an Important Cultural Property consisting of a pair of large, six-fold screens depicting a scene of swirling cherry blossoms in Nagatoro, as an example of a Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) that is perfect for spring. Enjoy the changing landscape as you move from one end to the other. Tsuchida Bakusen’sMaiko in a Garden, boasting an elaborate structure made up of a garden scene and a maiko(apprentice geisha), makes a return appearance to the museum for the first time in two years. Along with Important Cultural Properties by Nakamura Tsune and Kishida Ryusei, there are other notable oil paintings by Sekine Shoji and Saeki Yuzo, both of whom died remarkably young. There are also sculptures, whose plaster models have been designated as Important Cultural Properties, by Shinkai Taketaro and Ogiwara Morie.

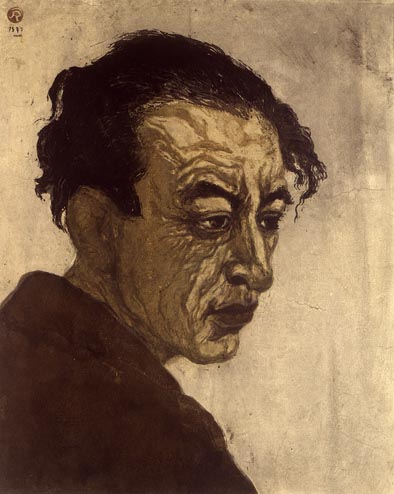

Room 2 Myriad Faces

In conjunction with the Kataoka Tamako exhibition (April 7–May 17), we present a group of works related to the theme of “portraiture.” Kataoka is known for her Tsuragamae (facial expression) series, in which she depicted figures from various historical periods. In this room, we find a prominent group of people including Sanyutei Encho, a comic storyteller from the Meiji era, the poet Hagiwara Sakutaro, the composer Gustav Mahler’s wife Alma, and the artists Kishida Ryusei, Bernard Leach, Saeki Yuzo, and Yasui Sotaro. One might begin by comparing the two portraits of Hagiwara, one by the printmaker Onchi Koshiro and the other by the sculptor Funakoshi Yasutake; or by comparing the differences between Saeki’s self-portrait and his life mask (a plaster cast made of his face while he was still alive). Also, the image of Sanyutei Encho that Kaburaki Kiyokata painted from memory seems different from the one in the photograph. Various differences between the people making the images and the methods used to make them, whether painting, print, sculpture, or photography, create different impressions of the same person. Which one is closest to the actual person? Or more than that, is it even possible to capture a constantly changing, living being in a static form like painting or sculpture?

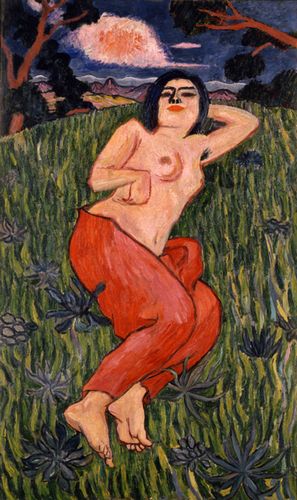

Room 3 Yorozu Tetsugoro Spirit

Yorozu Tetsugoro’s Nude Beauty is a familiar presence in the MOMAT Collection. But there are probably many viewers who have not had a chance to see the painting in a wider context. Thus, in this exhibit, we present all of the related works housed in the museum: seven oil paintings, three drawings, and two prints (including one deposited work). From Nude Beauty, an early effort, to the late work Nude, Resting Her Chin on Her Hand (Yorozu died young at 42), we can trace a single continuous flow.

One notable aspect is the changes in the three nudes. The strong impression created by the nostril and underarm hair in Nude Beauty belies one of the earliest examples of van Gogh’s influence in Japan. Five years later, Yorozu utterly transformed his style in Leaning Woman, featuring a nude figure that resembles a robot. This is one of the earliest Japanese works that displays the influence of Cubism, the movement associated with Picasso and Braque. In the last work, Nude, Resting Her Chin on Her Hand, the woman is placed in a provocative setting, sitting in front of a gold folding screen with her hair in the traditional Shimada-mage style of a Japanese bride. With beautiful black eyes, Yorozu had a calm appearance. But he actually possessed an uncontrollably rebellious spirit, constantly changing his style and betraying expectations.

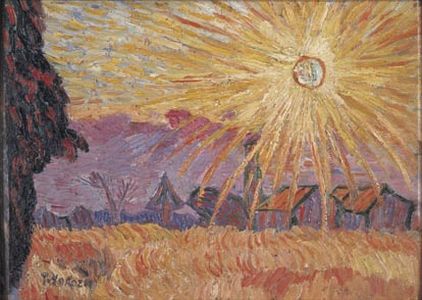

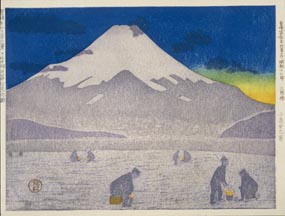

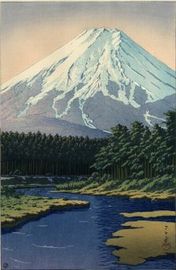

Room 4 Mt. Fuji

In conjunction with the Kataoka Tamako exhibition, we present a group of prints dealing with the theme of Mt. Fuji, which Kataoka returned to many times throughout her career. The image of Mt. Fuji is commonly associated with ukiyo-e prints from the Edo Period, but there was also an artist making works of this kind in 1939. The novelist Dazai Osamu wrote, “Hiroshige’s pictures of Fuji have 85 degrees. […] Hokusai’s almost all have a vertical angle of 30 degrees. […] But the real Fuji has obtuse angles and a dull expanse. […] It is by no means an outstanding, slender, tall mountain.” Also dating from the early Showa Period, works by Kawase Hasui, such as View of Mt. Fuji from Oshino and The Town of Yoshida in Clear Weather after Snow, minutely express the complex folds of the mountain while realistically conveying its mass. By placing the mountain beyond the roofs of houses and power lines, Koizumi Kishio incorporates the familiar form of Mt. Fuji into ordinary landscapes in the seriesThirty-six Views of Fuji, the Holy Mountain. Kawase traveled extensively, and Koizumi had an opportunity to climb Mt. Fuji. They began to make new images of the mountain based on the experience. Just as Dazai suggested, there are many different ways of expressing Mt. Fuji that diverge from the images in ukiyo-e prints.

Room 5 Comparing Umehara, Yasui, and Hasekawa

To a certain generation in Japan, Umehara Ryuzaburo (1888–1986), Yasui Sotaro (1888–1955), and Hasekawa Toshiyuki (1891–1940) are well-known painters. But that increases the potential for preconceptions about them. By placing the works side-by-side around the space, we hope to rediscover the special characteristics of each artist.

For example, both Yasui and Umehara made pictures of women clad in Chinese dresses. In comparing the two, we find that while Yasui attempted to create a complex spatial expression with the woman’s body as the central point, Umehara concentrated on depicting the woman’s character. And in comparing Yasui’s landscape paintings, we find that while they vary in terms of texture and depth, they are similar in that there are often trees in the foreground slightly obstructing our view. And though at the outset Umehara’s portraits were reminiscent of various artistic trends, after World War II it became obvious that he had attained his own unique style. Then there is Hasekawa. In his case, rather than evolving as the years passed, his brushwork seems to change with each subject.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building

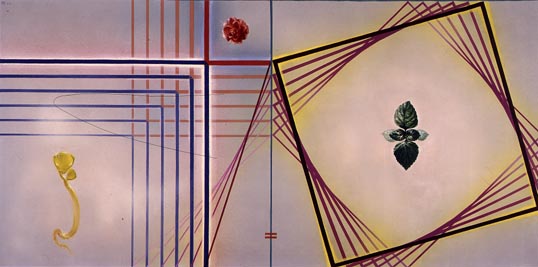

Room 6 Kitawaki Noboru: Between Chaos and Order

Most of us have probably had the experience of seeing a landscape or a person’s face in a rock, cloud or a spot on the wall. This type of accidental form discovered in an object is known as a “chance image.” Kitawaki Noboru (1901–1951) carved out a unique body of work in the mid-’30s by assimilating Surrealistic methods. At the core of his imaginative practice was a constant emphasis on “surprise” prompted by chance images. After first inspiring thePhysiognomical Series, a collection of “faces” concealed in a variety of ordinary objects and scenes, this concept gradually led Kitawaki in a different direction, in which he visualized the laws and underlying sense of order concealed in nature and society. As well as concrete images, Kitawaki adopted diagrammatic expressions to convey various concepts in his paintings.

These diagrammatic works provide us with some insight into the artist’s attitudes toward society at a time when the Sino-Japanese War was bogging down. In other words, by discovering a crystalline order by means of a rational method, Kitawaki attempted to transcend the extremely limiting and unstable nature of reality. To achieve this, he relied on models of plant growth and change, mathematics, and the Chinese I Ching. (Book of Changes).

Room 7 Butterflies Fly Away, Cats Play

With the enactment of the National General Mobilization Law in 1938, all Japanese citizens were compelled to aid in the war effort. Artists too were gradually forced to depict war-related themes. Some of these works, which are now generally referred to as “war paintings,” were known at the time as “operation-record paintings.” This makes it sound as if they were accurate records of each mission. But in fact, the paintings, larger in size and richer in color than a photograph, were expected to play a special role by expressing the conflict as something dramatic and sublime. Incidentally, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant said that the “sublime” was not especially related to beauty or ugliness but instead referred to the sensation that arose when a person is faced with something so overwhelming as to seem life-threatening. With this in mind, the “sublime” quality of these war paintings is not merely beautiful but often reveals something horrible. These works, with an inherent sense of shock prompted by such appalling scenes, captivated millions of viewers in countless exhibitions. In this display, we present Cats, a work by Fujita Tsuguharu that was made around the same time as his war paintings, andButterfly, which was also made during the war by the artist Aimitsu, who was sent to the front and died of an illness in Shanghai. Using the forms of non-human living creatures, both works seem to depict covert ideas.

Room 8 “Art is an explosion!”

Many viewers will recognize this famous exclamation by Okamoto Taro. The phrase itself comes from a TV commercial that was broadcast in 1981. But its spirit underlies Okamoto’s entire career. Rather than suggesting something destructive, Okamoto’s intention was to reject conventions and free the spirit. In other words, he was suggesting that art should call rules into question and uproot our values. Of course, Okamoto did not hold the patent on this notion. For example, in this room, focusing primarily on works from the 1950 and ’60s, we also present a work by Kayama Matazo. Having absorbed the methods of Picasso and Rousseau, the artist tried to incorporate then into Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting). There are also works by Domoto Hisao and Imai Toshimitsu, who hurled themselves into the Art Informel movement, designed to revolutionize pictorial space, by unifying the gesture of painting with the materiality of paint. We also present some sketches by the sculptor Yamamoto Toyoichi. To study how to depict mass, Kataoka Tamako, whose work is being shown in a special exhibition on the first floor, studied drawing with Yamamoto in the 1950s. In order to overcome her own limitations, Kataoka attempted to incorporate the accomplishments of other genres.

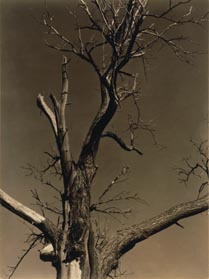

Room 9 Gazing at Plants and Vegetation

To coincide with this season, in which plants sprout and flowers bloom, we present a number of works dealing with vegetation. Each photographer’s interest varies along the form of the plants in the photograph – some emphasize details, others abstract forms, and still others turn their attention to vegetation and focus on the relationship between the plants and the space. As is often the case in Karl Blossfeldt’s works, he captures his subject close-up, and the form of the plant, enlarged to look much bigger than actual size, exudes a sense of artistry and vitality.

In contrast, Yamamura Gasho and Miyoshi Kozo capture both the vegetation and the surroundings in their photographs, emphasizing the relationship between plants and making individual plants stand out in each space, whether in a natural environment or a room. The photographers’ gazes are based on their interest in how environmental aspects such as water, light, the sky, and the earth, in which vegetation grows, appear in the works.

Room 10 Japanese Female Artists

In conjunction with the Kataoka Tamako exhibition, currently underway on the first floor, we present a group of works created almost entirely by Japanese female artists. The conditions we used to select the works are as follows: 1. the artist had to be dead; 2. they had to have continued working until the end of their lives; 3. the works had to be ones which were not scheduled to be used in an exhibition or loaned to another museum any time soon; and 4. the works had to be in satisfactory condition. In other words, the works were chosen in a fairly mechanical manner, and as you will see, they all deal with subjects such as women, children, mothers and children, and flowers. From the gender perspective, this bias in subject matter is a rather serious problem. From this, we can imagine that social pressure to behave “womanly” tended to force female artists to choose specific motifs. Perhaps the problem is exacerbated by the fact that the museum’s collection was originally subject to government approval, as the works were acquired by the Ministry of Education.

“The objective of art is ultimately down to the individual. Unless you are a woman, it is impossible to detect tenderness, gracefulness, and gentleness, and women must use their delicate sensibility and careful attention to understand themselves first, and then act faithfully to themselves and their careers.”

––Kanzaki Kenichi, “The Way of Women,” Toei, vol. 12, no. 3, March 1936.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Gallery 4 * A space of about 250 square meters. This gallery offers cutting-edge thematic exhibitions from the Museum Collection, and special exhibitions featuring photographs or design.

Room 11 “Paintings have to be bad.”

When Kataoka Tamako (1905–2008), whose work is featured in the Kataoka Tamakoexhibition, running from April 7 to May 17 on the first floor, was teaching at university she apparently said, “Paintings have to be bad.” By this, she may have meant that it was pointless to try and show people how good you were at drawing or painting. Instead, it was necessary to move beyond that point and reach a unique approach to lines, shapes, colors, structure, and content that was apt to be seen by others as inept. With this in mind, we have selected a group of works that look “bad.” Komatsu Hitoshi painted the landscape that was visible from his house over and over again. Kusama Yayoi incorporated wavering polka dots and nets, which arise out of visual hallucinations and oppression, into her paintings. Jean Dubuffet had a long interest in work by children and the disabled. And Iwasaki Hajin was known as an unconventional artist-monk. In looking at these artists’ works, we realize that the definition of “bad” is quite expansive. Some sketches by Takayama Tatsuo, are also impressive for their unique playfulness.

Room 12 “This Giant Junkyard Where Everything Falls Apart and Rots”

The title is a quote from Takamatsu Jiro (1936–1998), an artist who began his career in the 1960s. Like Takamatsu, the majority of the artists represented in this exhibit were born in the 1930s. As elementary or junior-high school students, this generation saw Japan’s defeat in the war and watched as the values that their parents had worked to build were destroyed before their very eyes. As university students or workers, they saw the country enter an unprecedented period of economic growth and confronted a sense of emptiness in regard to the true nature of things as a new peaceful society began to overflow with material objects. With this background in mind, we can clearly identify several features of works from this generation. There is, for example, a deliberate effort to create work that defies the framework of “painting” and “sculpture” as defined by the previous generation. Some artists used mass-produced items like syringes and plastic dolls, and huge quantities of waste as materials. And there is also a distinct effort to devise methods of encountering the world using things that people would not normally see, such as the inner lining of a glove and the instant that a person’s hand makes contact with a ball or stick. Like a child asking “Why?” about every single thing, these artists’ works were made to review and revise the rules made by the previous generation from scratch.

About the Exhibition

- Location

-

Art Museum Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- 会期

-

March 7, 2015 – May 17, 2015

- Time

-

10:00 – 18:00

*Last admission is 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

Closed on Mondays (except March 23, 30, April 6 and May 4)

- Admission

-

Adults ¥430 (220)

College and university students ¥130 (70)

*Including the admission fee for MOMAT Collection and /Osaka Expo ’70 Design Project.

*The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more.

*All prices include tax.

*Free for high school students, under 18, seniors(65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

*Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Member’s Card admits two persons free).

*Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge. - Free Admission Days

-

*Collection Gallery and Gallery 4 only

Free on April 5, May 3 and May 17 - Organized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo