Exhibitions

2017-2 MOMAT Collection

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors, Gallery 4

The collection exhibition from November 14, 2017 – May 27, 2018

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection! In this ongoing series of exhibitions, we present trends in modern and contemporary Japanese art from the 20th century to the present including references to international connections.

The “Highlights” section (Room 1, 4th floor) is filled with a selection of masterpieces from the museum collection. The displays in Rooms 2 to 12 are arranged in more or less chronological order. Since the items in each room are based on a particular theme, such as “The Sun, Me, and Women” and “The Great Kanto Earthquake,” we hope that you will enjoy comparing them. Considering the historical background of the works should also make for an enjoyable viewing experience. Other rooms contain themes related to the Kumagai Morikazu exhibition (Dec. 1–March 21) and the Yokoyama Taikan exhibition (April 13–May 27), both held on the first floor.

In Room 9 (3rd floor), we present an exhibit on Robert Frank, one of America’s preeminent photographers, featuring a group of recently acquired works, and in Gallery 4 (2nd floor), an exhibit titled “Refugees.”

In addition, “Spring Festival in MOMAT” will be held in the spring of 2018 to coincide with cherry-blossom season. Among the works awaiting you there will be Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring (on view from March 20 to May 27).

We hope that you enjoy the many and varied pleasures of the MOMAT Collection.

translated by Christopher Stephens

Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 14 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as Important Cultural Properties. These include nine Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, four oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro , Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Yasuda Yukihiko,Camp at Kisegawa, 1940/41 (Exhibit Date: January 16 – March 18, 2018)

- Yorozu Tetsugoro, Nude Beauty , 1912 (Exhibit Date: Feburary 20 – May 27, 2018)

- Kawai Gyokudo, Parting Spring, 1916 (Exhibit Date: March 20 – May 27, 2018)

- Hishida Shunso, Bodhisattva Kenshu, 1907 (Exhibit Date: March 20 – May 27, 2018)

- Please visit the Important Cultural Property section Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F (Fourth floor)

Room 1 Highlights * This section presents a consolidation of splendid works from the collection, with a focus on Master Pieces.

Room 2– 5 1900s-1940s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

A Room With A View

Reference Corner

Room 1 Highlights

The MOMAT Collection, drawn from the museum’s holdings, consists of over 200 works displayed over a 3,000-square meter area. To start off the exhibition, we present the “Highlights” section, consisting of some of the collection’s most essential works, including Important Cultural Properties. For the walls of this newly established space (part of a 2012 effort to renovate the collection galleries), we have selected navy blue to create a more beautiful contrast with the works. And to eliminate the glare of glass cases, we have chosen mat black for the floor.

In the Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) section, divided into three exhibition periods, we present Hirafuku Hyakusui’s Rough Coast and Kayama Matazo’s Cranes, both of which combine realistically rendered birds with decorative elements (on view until Jan. 14); Yasuda Yukihiko’s Camp at Kisegawa (Important Cultural Property; on view from Jan. 16 to March 18), which depicts the first meeting in 20 years between Minamoto no Yoritomo and Minamoto no Yoshitsune; and Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring, a richly poetic celebration of cherry blossoms (Important Cultural Property; on view from March 20 to May 27).

Meanwhile, in the Western-style painting section, we present Harada Naojiro’s Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon (also an Important Cultural Property) as well as a group of important works by Koide Narashige, Sakamoto Hanjiro, Suda Kunitaro, Yasui Sotaro, and Umehara Ryuzaburo, who were deeply aware of differences between the East and West and of realism, and devoted themselves to producing Japanese-style oil paintings. The display also includes recent acquisitions by the European painters Cézanne and Matisse.

Room 2 Before and After the Bunten Exhibition

Following the inauguration of the Meiji government in the late 19th century, Japan established a variety of cultural concepts and systems that were based on a Western model. It was during this period that painting also came to be divided into two categories. The term “yo-ga” (Western-style painting) was used to refer to oil painting, which had its roots in the West, while “Nihon-ga” (Japanese-style painting) denoted any painting that made use of time-honored and traditional Japanese techniques. This genre division was further reinforced at a government level with the opening in 1907 of the Bunten exhibition, an annual event sponsored by the Ministry of Education that consisted of three divisions: Western-style painting, Japanese-style painting, and sculpture.

Here, we feature works from around the time of the first Bunten exhibition, primarily depicting the human figure. Asakura Fumio’s The Grave Keeper is a statue of an ordinary man, not a god, a Buddha, or a legendary figure from history. Nakamura Fusetsu was a constant presence at the Bunten, frequently serving as a judge from the first exhibition onward, and also continually showing work there. He distanced himself from the “new school” led by Kuroda Seiki, adopting a style based on traditional French painting, and producing imposing historical paintings that depicted East Asian subjects.

Here, in conjunction with the museum’s spring festival, Nihon-ga paintings include Kikuchi Hobun’s Fine Rain on Mt. Yoshino, and yo-ga include Fujishima Takeji’s Perfume.

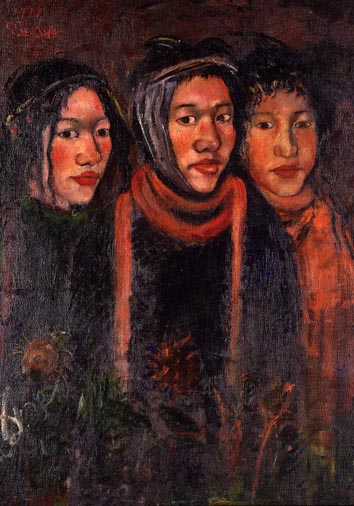

Room 3 Art in the 1910s: The Sun, Me, and Women

“I am searching for absolute freedom in the art world. Thus, I am attempting to recognize the infinite authority of the artist’s Persoenlichkeit [personality]…. Even if someone painted a green sun, I would not criticize them.” This is a passage from “Green Sun,” an essay written by Takamura Kotaro in 1910. Extolling an absolute way of seeing and feeling that would even allow an artist to alter the nature of the outside world, the text heralds the start of Taisho Democracy.

The artists behind these movements were fanatical about Post-Impressionist painters like Van Gogh and Gauguin. They had also discovered the power of self-expression. In this room we present art from the Taisho Era (1912–1926) with the themes of “the sun,” “self-portraits,” and “women as muses.” All are motifs that aptly represent features of art of this period, and here we may recall that the 1911 inaugural issue of the magazine Seito (Bluestocking) contained an article beginning with the phrase “In the beginning, woman was the sun” a quotation from women’s liberation activist Hiratsuka Raicho. This is because all of the creators of these artistic paeans to “personality” and “freedom” were male.

Room 4 September 1, 1923

A massive earthquake of magnitude 7.9 struck the Kanto region at 11:58 AM on September 1, 1923. The damage caused by fires was much greater than that caused by collapsing buildings, and a fire that broke out immediately after the earthquake devastated the center of Tokyo. It is said that 900,000 people were affected, 105,000 people died or went missing, 110,000 buildings collapsed, and 210,000 buildings burned to the ground (figures approximate).

This Great Kanto Earthquake, which destroyed Japan’s capital, had an impact comparable to the devastation of European cities in World War I, and transformed Japanese society in many ways. In art, it marked a decisive line between works of the Taisho Era (1912–1926), which celebrated individuality and freedom, and those of the prewar era, characterized by themes of the city, machines, and the masses.

Here, we present watercolors by Sogame Hirotaro, who documented the scene immediately after the disaster, and prints depicting Tokyo rapidly emerging from the ruins to transform into a modern city.

Room 5 Art from the Mid–1920s to the Late 1930s: The Machine and the Märchen (Fairytale)

Here we introduce two very different “worlds” that artists encountered during the period of reconstruction after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

First is the world of the machine. During the 1920s and 1930s, with the progress of technology accompanying modernization, a new aesthetic appreciation of machines arose. However, while machinery was an object of admiration, it played an ambivalent role as human beings seemed to become mere cogs in some machine, gradually stripped of their humanity. Akutagawa Ryunosuke wrote the novel, Haguruma (Spinning Gears) in 1927, while in 1930 Yokomitsu Riichi published Kikai (Machine), including the following passage: “There are invisible machines constantly watching over us, measuring and gauging us at all times and moving us along predetermined paths.”

The other world is that of Märchen (fairytales). In 1924, Miyazawa Kenji published The Restaurant of Many Orders. Set in the ideal village of Ihatove, the allegorical fable featuring anthropomorphized animals and humans seems at first to have little direct relevance to reality. However, for Miyazawa, the Märchen format was a very realistic means of expressing and realizing his vision, that of the salvation (or deconstruction) of our world.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building

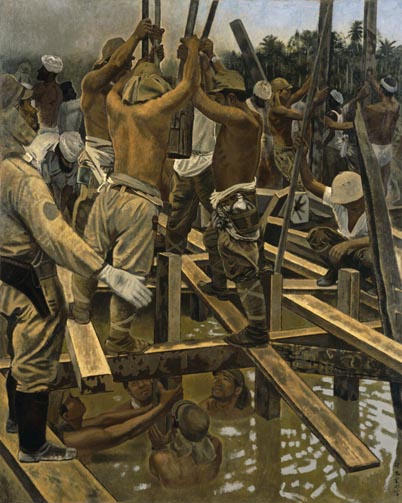

Room 6 Southward

During World War II in the Pacific, the Japanese Army and Navy commissioned War Record Paintings and dispatched painters to the front lines to produce them. Fujita Tsuguharu, Inokuma Genichiro and many other painters took these commissions, some going to China and others to the South Pacific. This room focuses on works by painters with southern destinations. While they were commissioned to paint the war for documentary purposes, the painters seem to be interested in the natural landscape, quite different from that of Japan.

As the war turned ever more disadvantageous for Japan, it became too risky for painters to journey to the front lines, so they assembled previous sketches, photographs, and accounts from soldiers and used their imaginations. At this point the works could probably no longer be called “war record paintings,” but in fact with all war paintings it is difficult to separate fact from fiction. By contrast, the picture postcards young painter Asahara Kiyotaka sent his new bride from Burma (present-day Myanmar), where he was stationed as a private, are tiny yet conveys a convincing reality. Asahara went missing not long after sending these postcards.

Room 7 Two Avant-Gardes

“Avant-garde” was originally a military term meaning “advance guard,” the army corps that ventured out ahead of the rest of the army to reconnoiter. It came to be used in a revolutionary political sense, and then around the 1930s, came to refer to innovative art movements pioneering new forms of expression. In Japan such movements were suppressed during the wartime period.

After the war, artists who once again took up avant-garde art divided into two camps, those purely pursuing new forms of visual expression, and those who sought to transform society through such new modes of expression. Yamashita Kikuji and others belonging to the latter group created works delivering strong messages, which reconfigured the complex postwar social circumstances from a critical standpoint while incorporating elements of the fantastic. The same period is also characterized by interdisciplinary collaborations, with artists and writers working together to explore new creative avenues. Well-known examples are the groups Yoru-no-kai (The Night Society) founded by Okamoto Taro and Hanada Kiyoteru, and Abe Kobo and Katsuragawa Hiroshi’s Seiki (Century).

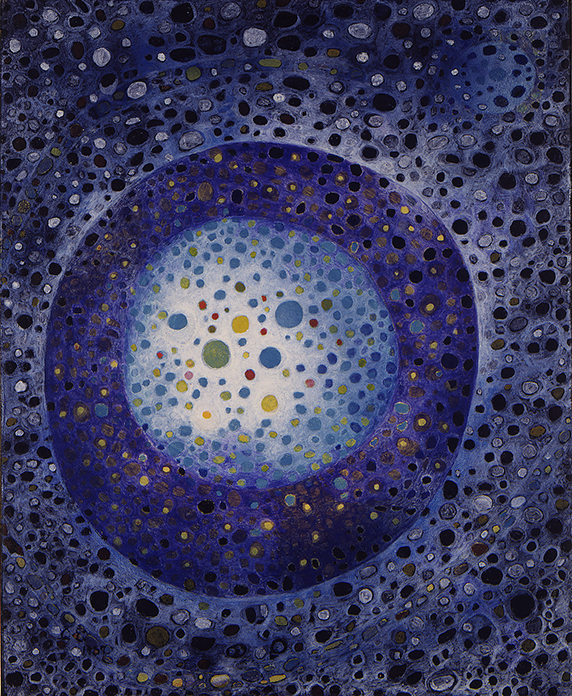

Room 8 Art of Life and Death

A retrospective of the work of Kumagai Morikazu will be held from December 1, 2017 to March 21, 2018 on the first floor of the museum. As the subtitle The Joy of Life indicates, his work turns a gaze full of wonder on life itself, but the artist also witnessed a great many deaths. This room explores this contradiction by bringing together postwar works dealing with themes of life and death.

Life and death are both deeply personal experiences, and the most universal themes. In representational painting, life is often symbolized with mother-and-child images and death with corpses or skeletons, but in abstract painting it is represented with more primal imagery. For this reason, images of life and death can appear almost indistinguishable, as in the work of Nambata Tatsuoki. On a fundamental level, it can indeed be difficult to distinguish between life – the emergence of form from formlessness – and death, the reverse process. Because the afterlife is invisible, these themes drove the painters to tackle the most essential challenge of art, to render visible that which cannot be seen.

Room 9 Robert Frank, The Lines of My Hand (Exhibit Date: November 14, 2017 – January 14, 2018)

MOMAT has newly acquired 145 works by Robert Frank formerly owned by Motomura Kazuhiko (1933–2014), head of Yugensha, which published books of Frank’s photos in Japan. Frank was one of the most important photographers of the late 20th century, and the works, including some of his most important pieces, are exhibited here in three periods, each featuring different pieces.

In this first period, we present works from The Lines of My Hand, published by Motomura in 1972. This book was produced after Motomura proposed the creation of a new photo book to Frank, who had primarily switched to making films after the success of the photo book The Americans (published in France in 1958 and the US in 1959), which established his reputation. An anecdote relates that Motomura, a Frank devotee since seeing The Americans, traveled to New York in 1970 to the photographer and request his cooperation, craving for his new works . The book design was by Sugiura Kohei. The Lines of My Hand, structured as an autobiographical work featuring a wide range of photographs from the dawn of his career through the early 1970s, played a major role in shifting Frank focus from film back to photography again.

Room 9 – 2 Robert Frank, The Lines of My Hand (Exhibit Date: January 16 – March 18, 2018)

In this period, we present works from “Flower is Paris,” the first chapter of Flower is… (1987), which was the second book published by Motomura following The Lines of My Hand (1972). These photos were taken when Switzerland-born Frank, who had moved to the US, returned to Europe and was living from 1949 to 1951 in Paris, where he was fascinated by people selling and buying flowers on the street and photographed them on an ongoing basis. Flower is…, which begins with this beautiful series, is dedicated to Andrea, the photographer’s daughter who died in an airplane crash in 1974.

Room 9 – 3 Robert Frank, The Lines of My Hand (Exhibit Date: March 20, 2017 -May 27, 2018)

The third section consists primarily of works from “Mabou is Waiting,” the third chapter of the 1987 photo book Flower is … Since 1969, Frank has had a house in Mabou in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and has been based there as well as in New York. Many of the photos in The Lines of My Hand (1972) and Flower is… (1987), published by Motomura, were provided by Frank in a state that was ready for publication, and Motomura was never asked to return them. The two remained lifetime friends and Frank repeatedly gave Motomura more works [during their visits to one another]. Frank inscribed several of the works shown here with dedications that testify to the bond between the two.

Room 10 120-year Anniversary of the Nihon Bijutsuin

In conjunction with Yokoyama Taikan: The 150th Anniversary of His birth (April 13–May 27, 2018), held on the first floor, in this room we showcase the Nihon Bijutsuin (the Japan Art Institute), one of the main places Taikan was active.

The Nihon Bijutsuin was primarily founded by Okakura Kakuzo (or Okakura Tenshin, 1863–1913), a Meiji-era (1868–1912) thinker who was dismissed as the head of Tokyo School of Fine Arts 120 years ago, in 1898. Since then, the Institute has relocated to a rural area (1906), temporarily suspended its activities (1908), resumed them (1914), and been incorporated as a foundation (1958), but its activities continue to this day.

Respecting the East Asian classics while striving for innovation – this policy of the Nihon Bijutsuin has gone unchanged since its founding. The artists belonging to it conducted independent research, and sometimes created techniques and trends that the leaders did not expect. These include Meiji-era Moro-tai (lit., “unclear form”) and the detailed rendering of the Taisho Era (1912–1926). Another major feature of the Institute was respect for individualistic artists such as Ogawa Usen and Kataoka Tamako.Please enjoy these major works by artists who played leading roles at the Nihon Bijutsuin, and the diversity of expression they brought to the world of modern Japanese painting.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Room13(Gallery 4)

* A space of about 250 square meters. This gallery offers cutting-edge thematic exhibitions from the Museum Collection, and special exhibitions featuring photographs or design.

Room 11 Lee Ufan, The Art of Margins

Yokoyama Taikan, the focus of the retrospective on the first floor (April 13–May 27, 2018),was one of the preeminent Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) painters. When someone asks, “What are the distinctive features of Nihon-ga?”, many of us would probably say the “beauty of the margins.” Thus, we have decided to present a special exhibit on Lee Ufan, the artist who wrote a book called The Art of Margins. It is interesting to note that a margin can be created simply by painting a dot on the canvas. In other words, some type of action is necessary, and a margin emerges after the action is performed. The ex-post-facto nature of margins makes it clear that they cannot be controlled, and in as much as Lee sees this quality as the essence of art, his art is extremely contemporary.

Room 12 Uncertain Photographs: Japanese Photography of the 2000s

In this section, we present the works of four Japanese photographers that were produced in the 2000s. Suzuki Risaku shoots the mountain in southern France that were famously depicted in Cézanne’s paintings. Homma Takashi questions our expectations of portrait photography.By capturing the surface of the water in the foreground, Narahashi Asako upends the focus and the subject depicted in her works. Kitano Ken creates his photographs by shooting each member of a given group separately and then printing all of the pictures together. All of these works can be seen as an attempt to question certainty or uncertainty through the use of the photographic medium. The 2000s was also an era that saw the rapid spread of digital photography. Though it might seem as if Kitano’s pictures were created digitally, they are actually multiple exposures made with a physical negative shot on 35mm film.

Event

Takashi Homma Artist talk

Takashi Homma New Documentary Movie

First, jay comes.

Artist talk (15 min.) & Film screening (225 min.)

- Date

-

Saturday, March 24, 2018

- Time

-

Doors open 14:45

Talk 15:15-15:30

Screening 15:30 -19:15

(Museum is open until 20:00 on the day.) - Location

-

Lecture hall, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

- Free admission, no reservation required, 160 seats.

About the Exhibition

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors, Gallery 4

- Date

-

November 14, 2017 – May 27, 2018

- Time

-

10:00-17:00 (10:00 – 20:00 on Fridays and Saturdays)

*Last admission is 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

※Closed on Mondays (except January 8, February 12, March 26, April 2, 30, 2018) and December 28, 2017 – January 1 and January 9, February 13,2018

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)*The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more.

*All prices include tax.

*Free for high school students, under 18, seniors( 65 and over ), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

* Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission ( a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free ).

*Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

*Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID. - Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 pm on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Free Admission Days

-

Collection Gallery

Free on November 15, December 3, 2017, January 2, 7, February 4, 23, March 4, April 1, May 6, 18, 2018 - Organized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo