Exhibitions

2021-1 MOMAT Collection Special

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

The collection exhibition from May 25 to September 26, 2021

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection! We are pleased to present a special exhibition, in conjunction with the Olympic and Paralympic Games, which traces the course of modern and contemporary Japanese art through works from the museum’s collection.

After centuries of isolation during the Edo Period (1603-1868), Japan opened its doors to the world, and aspects of Western culture were introduced to the nation with incredible rapidity, art being among them. From then to now, Japanese artists have explored their own identities, moving back and forth between admiration for the West and alignment with the nation’s own traditions. Some have turned their eyes to the realities of rapidly modernizing Japanese society, while creating art that asks questions on a personal level. This exhibition follows the arc of this history, presenting approximately 250 works including eight Important Cultural Properties, with some of the works shown in the first term (May 25-July 18) replaced by others during the second term (July 20-September 26). Also, we invite you to enjoy the exhibit in Gallery 4 on the second floor, which explores developments in steel sculpture with David Smith’s Circle IV, purchased in 2017, as a particular highlight.

translated by Christopher Stephens

Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 15 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as Important Cultural Properties. These include nine Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- May 25–September 26

-

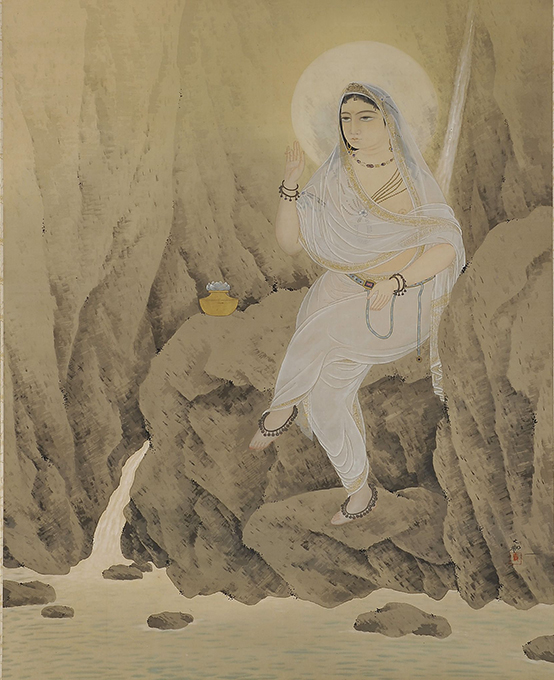

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Wada Sanzo, South Wind, 1907

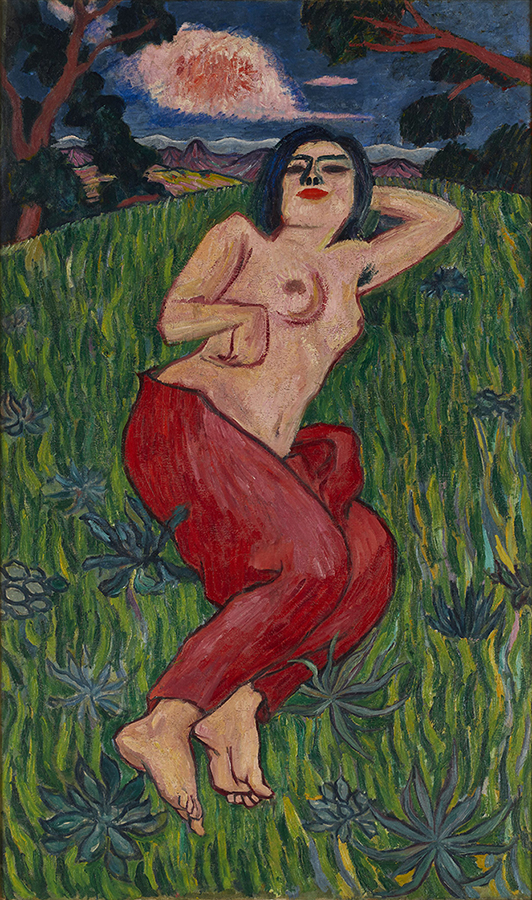

- Yorozu Tetsugoro, Nude Beauty, 1912

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915

- Nakamura Tsune, Portrait of Vasilii Yaroshenko, 1920

- Yokoyama Taikan, Metempsychosis, 1923

- First half: May 25–July 18

-

- Tsuchida Bakusen, Serving Girl in a Spa, 1918

- Second half: July 20–September 26

-

- Yasuda Yukihiko, Camp at Kisegawa, 1940/41

- Please visit the Important Cultural Property section Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

- Yasuda Yukihiko, Camp at Kisegawa, 1940/41

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F (Fourth floor)

Room 1 Highlights * This section presents a consolidation of splendid works from the collection, with a focus on Master Pieces.

Room 2– 5 1900s-1940s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

A Room With A View

Reference Corner is currently out of service.

Room 1 Traditional Painting in the Modern Era

Exhibited in this room are some classic works of Nihonga dating from the Meiji Era (1868-1912) through the early prewar years of the Showa Era (1926-1989). After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the term Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) came to be used as a general term for painting that adhered to the traditional usage of nikawa (animal-derived glue) as a vehicle for pigment, to distinguish it from the increasingly common yoga (Western-style painting), i.e. oil painting, which had roots in the West. In light of these origins one might say that the raison d’être of Nihonga was to carry on tradition, but in fact from its earliest days Nihonga painters were already seeking new modes that corresponded to the changing times. This is visible in a work such as Nio [Buddhist guardian] Seizing an Evil Spirit (on view July 20 – September 26) by Kano Hogai, an artist active in the 1880s who endeavored to improve traditional painting under the guidance of Ernest Fenollosa, who had come to Japan from the United States. In the works shown in this room we can see modern interpretations of Japanese (or East Asian) traditions, such as flatness and decorative elements. At the same time the influence of Western art cannot be overlooked, and is manifest in more vivid palettes and different ways of handling light.

Room 2 Art of the Meiji Era

During the Meiji Era (1868-1912), Japanese artists were learning about “art” (as in fine art, or art for art’s sake) from the West, and seeking to make it their own. For example, they studied and sought to master Western oil painting’s techniques of shading and perspective, intended for realistic depiction of three-dimensional objects, which was not found two-dimensional traditional Japanese painting. In Harada Naojiro’s Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, we see a combination of East Asian themes and Western-style rendering.

It was not only technical aspects that were being studied but also various systems related to art, such as art’s role in society and the structure of exhibitions where people appreciate works of art. The establishment of a modern “art world” in Japan, modeled on that of the West, can be roughly dated to 1907. This was the year the Bunten (Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition) first took place, with entries accepted in the three categories of Nihonga, Western-style painting, and sculpture. Wada Sanzo’s South Wind won the top prize in the Western-style painting category at that first exhibition.

Room 3 Focus on Yorozu Tetsugoro and Kishida Ryusei

The Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition (Bunten), first held in 1907, provided artists with opportunities to earn public acclaim, but it also created a framework of values that defined the conventions of the day. At the same time, during this period there was a growing tendency to respect artists’ individuality and freedom to look beyond the boundaries of convention. This was exemplified by the sculptor Takamura Kotaro, who published the text A Green Sun in 1910. Takamura formed the artist group Fusain-kai in 1912 with Yorozu Tetsugoro and Kishida Ryusei, and they produced works that diverged from the Bunten’s value system. Yorozu’s graduation work for the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, Nude Beauty, is a seminal work embodying this trend, in which we see not only the influence of Vincent van Gogh but also a manifestation of the artist’s inner, individual life. Kishida Ryusei was also influenced by Van Gogh early on, but went on to adopt a more direct approach to his subjects, and developed his own mode of realism in works such as Road Cut through a Hill.

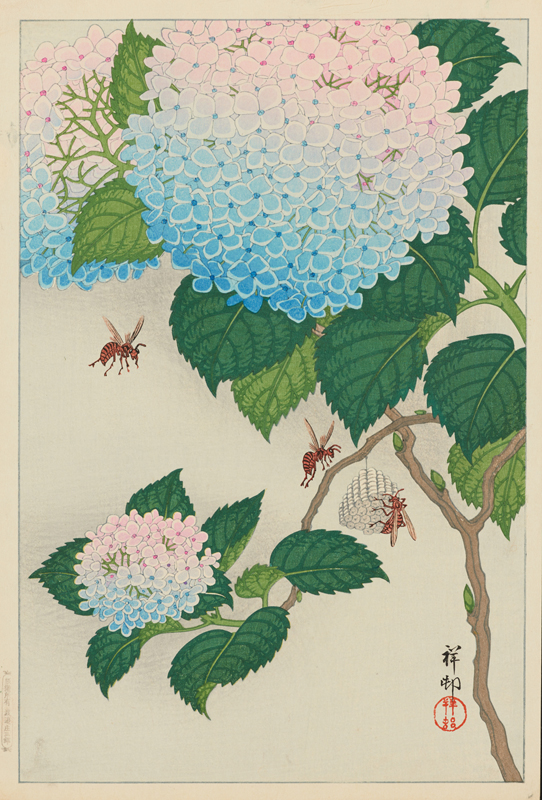

Room 4 Ohara Koson (Shoson)

(Exhibit Dates: May 25–July 18)

Ukiyo-e, popular with city dwellers during the Edo Period (1603-1868), gradually declined from the Meiji Era (1868-1912) onward as new printing techniques from the West, such as lithography and photography, made inroads in Japan. However, there was also a contingent of printmakers that aimed to revitalize the traditions of ukiyo-e. It grew increasingly prominent during the Taisho Era (1912-1926) and came to be known as the Shin-hanga (new prints) movement, producing many works that were exported and prized overseas. Among the best-known figures are Hashiguchi Goyo and Ito Shinsui, who specialized in bijinga (lit. “pictures of beautiful women”), and landscape printmaker Kawase Hasui, but this exhibit focuses on Ohara Koson (a.k.a. Shoson), known for his works in the flower-and-bird genre. He began as a Nihonga (modern Japanese-style painting) artist and went by the name Koson, but in 1926 he adopted the name Shoson and went on to gain popularity with a large number of flower-and-bird prints both realistic and decorative in character, produced at the Shin-hanga printmaking studio Watanabe Hangaten. Thereafter he was largely forgotten in Japan, but there are large collections of his works in the Netherlands and the US, and recently he has been enjoying a critical reappraisal in his home country as well. The MOMAT collection contains works formerly belonging to ukiyo-e scholar Fujikake Shizuya, and here we present 32 of them, divided into a first and a second term.

Room 5 Nakamura Tsune and His Circle

The Taisho Era (1912-1926) was characterized by veneration of artists’ individuality, and in this the role of people who supported them cannot be overlooked. Soma Aizo and Kokko, a husband and wife who opened the bakery Nakamura-ya in 1901, were lovers of art, and after they moved their business to Shinjuku in 1909 it became a gathering place for many artists including Ogiwara Morie, Tobari Kogan, Nakamura Tsune, Nakahara Teijiro, and Yanagi Keisuke. Ogiwara, who had studied under Auguste Rodin, secretly harbored feelings for Soma Kokko which he sublimated in works such as Priest Mongaku and Woman, while Nakamura Tsune felt similarly toward the Somas’ cherished daughter Toshiko, but this only resulted in heartbreak, which he gave metaphorical expression in the wind-tossed trees of Landscape, Island Oshima Toshiko subsequently married Rash Behari Bose, an Indian independence activist in exile from his home country, and Nakamura Tsune portrayed Vasili Eroshenko, a poet and musician who had come to Japan from Russia, examples of the international quality of the Nakamura-ya scene.

Another noteworthy fact is that, as it happened, all the artists represented in this room died relatively young. One could say that their all-too-short lifetimes were fully consumed with the passionate pursuit of art.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s

From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 Umehara Ryuzaburo and Yasui Sotaro

Umehara Ryuzaburo and Yasui Sotaro followed similar trajectories in many ways: both were born in Kyoto in 1888, were students of Asai Chu before studying abroad in France, and after returning to Japan explored the essence of Japanese art, coming to be recognized as two giants of Japanese oil painting from the 1930s onward and simultaneously receiving the Order of Culture in 1952. However, there were significant differences in the artistic directions they pursued. Viewing the works from their time abroad, it is evident that Umehara was strongly influenced by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Yasui by Paul Cézanne and Camille Pissarro. After returning to Japan, Umehara pursued his own distinctive experimentation primarily in terms of color, and Yasui in terms of form. Umehara began adding traditional Japanese mineral pigments to oil paint in the mid-1930s, producing vibrant colors that are particularly notable in his works depicting Beijing. Meanwhile, Yasui applied his extraordinary draftsmanship skills to lively portraits, exemplified by Portrait of Chin-Jung, featuring exaggerated and stylized forms, and to lush landscapes such as Oirase Stream. While their explorations took them in different directions, the works of both artists convey a never-ending pursuit of the question: “What does innately Japanese oil painting look like?”

Room 7 Fujita Tsuguharu

Many of the modern Japanese oil painters whose works we have seen thus far admired, and were influenced by, the art of the West while also exploring their own identities. Fujita, meanwhile, was probably the first Japanese oil painter to achieve a successful career in the West by actively deploying characteristics of Japanese art. He moved to France in 1913 and continued developing his signature style during World War I, arriving in the 1920s at delicate portrayals of women with smooth, white porcelain-like skin and extremely fine outlines produced with the very thin brushes of Nihonga (Japanese-style painting). These were highly lauded in the Parisian art world. He subsequently returned to Japan during World War II and produced War Record Paintings in a manner reminiscent of Western historical painting. In his great stylistic versatility, we see an artist who knew exactly what his audience was seeking. Postwar, he was criticized for his complicity in the war and went back to Paris again, never to return to Japan, but he nonetheless remains a crucial figure in any consideration of the relationship between modern Japanese art and the West.

Room 8 Gutai and Art Informel

The Gutai Art Association was formed in Osaka in 1954, with Yoshihara Jiro as its leader. Based on Yoshihara’s dictum “Do what no one has done before,” its members ventured boldly beyond the established boundaries of art. Shiraga Kazuo painted with his feet, Motonaga Sadamasa poured paint on diagonally positioned canvases, Tanaka Atsuko made a dress of colored light bulbs and tubes, Kanayama Akira painted using remote-controlled toy cars, and Murakami Saburo staged performances in which he burst through large sheets of paper stretched across a series of frames. The group’s uncompromisingly forward-thinking practices have increasingly won international acclaim in recent years.

The work of the Gutai artists bore relation to the abstract painting movement known as Art Informel, which flourished mainly in France in the late 1950s. Imai Toshimitsu and other Japanese artists studying abroad in Paris also took part in this movement, and the evolution of Imai’s work is of particular interest. The rough brushstrokes that characterized his work when he first aligned himself with the movement gradually became more refined, and Japanese elements were added. We can also see Japanese elements, in the context of abstraction, in the works of Tabuchi Yasukazu and Sugai Kumi, also active in Paris around the same time.

Room 9 Tomiyama Haruo and Linguistic Sense Today (First half: May 25–July 18)

What was Tokyo like in 1964, when the Olympics were last held here? “Linguistic Sense Today,” a series of photographs and essays that ran in the Asahi Journal in 1964 and 1965, was a vivid portrayal of Japanese society, then enjoying dramatic economic growth but showing various signs of strain and imbalance due to the frenetic pace of this growth. Rather than being harshly critical, however, the photographs are imbued with an ironic sense of humor. The title of each photo consists of two kanji characters, but the titles are not based on the photos, rather the reverse. The series consisted of texts accompanied by photographs, and the writers of the texts (including Abe Kobo and Oe Kenzaburo) selected kanji compounds that reflected some aspect of the social situation each week, which were presented as themes for the in-house photographers. They then went out into the streets to find fitting subject matter before the deadline, with the single most spot-on photo selected for publication that week. Of the 68 articles in the series, 42 featured photographs by Tomiyama Haruo, who compellingly captured the mid-sixties scene in a manner that feels no less fresh and contemporary today.

Room 9 Takanashi Yutaka, Otsukaresama (Second half: July 20–September 26)

What was Tokyo like in 1964, when the Olympics were last held here? It was during this period that television rapidly became commonplace in ordinary households, precisely because people wanted to enjoy the Olympics at home, and the emergence of TV led to the rise of TV personalities. Otsukaresama is a series of portraits by Takanashi Yutaka of popular personalities of the day, which was serialized in Camera Mainichi over the course of a year, and for which he won a prize for emerging photographers from the Japan Photo Critics Association.

Takanashi saw on-camera celebrities as people behind “masks” that enabled viewers to have vicarious experiences through them, and believed that by analyzing those masks, it was possible to understand the tastes and social conditions of the people at that time. The neutral white backgrounds of the photographs emphasize the qualities of the televised performances for which these stars were known.

Room 10 Yokoyama Taikan and Takeuchi Seiho (First half: May 25–July 18)

(Exhibit Dates: May 25–July 18)

(Exhibit Dates: May 25–July 18)

During the term from May 25 to July 18, the area in the rear of Room 10 will feature the works of Yokoyama Taikan and Takeuchi Seiho. The two were viewed as masters of equivalent stature, referred to collectively as “Taikan in the east [i.e. Tokyo] and Seiho in the west [i.e. Kyoto],” and both received the Order of Culture in its first year, 1937, for their significant roles in the advancement of modern Nihonga (Japanese-style painting). Taikan was inspired by his teacher Okakura Kakuzo (Tenshin) to render air and light in a manner related to Western painting, and contributed to development of the blurred, outline-free morotai style. Meanwhile, Seiho sought to break free of artistic conventions by applying Western-style observation of nature to the traditional sketching practices of the Maruyama-Shijo School. While these two artists followed different paths, they both sought to bring Japanese painting into a new era by re-examining the traditions of Japan (or East Asia) while engaging with Western perspectives.

The area toward the front of Room 10 features Higashiyama Kaii, one of the most prominent figures in postwar Nihonga. His practice was to begin with sketches of actual views from life, but to build these into solid and concise compositions free of unnecessary detail, resulting in lyrical landscape paintings that would resonate with any Japanese viewer as depictions of the country’s primordial scenery.

Room 10 Kayama Matazo (Second half: July 20–September 26)

During the term from July 20 to September 26, the area in the rear of Room 10 will feature the works of Kayama Matazo. After Japan’s 1945 defeat in World War II, rejection of prewar culture led to a backlash against all manner of traditions. Kayama, whose painting career began in this context, belonged to a group of Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) practitioners who aimed to create new Japanese painting rooted in globalism, and exhibited animal paintings influenced by the cave paintings of Lascaux and by Pablo Picasso. However, he subsequently rediscovered the classical painting of Japan (East Asia) and his style underwent dramatic change. Works referencing Yamato-e (classical Japanese painting) and the Rinpa School, such as Waves in Spring and Autumn, or those influenced by Chinese ink wash painting such as Snowy Landscape in the Northern Song Manner, emerged from his novel reinterpretations of Japanese and East Asian traditions.

Room 10 Higashiyama Kaii (May 25–September 26)

The area toward the front of Room 10 features Higashiyama Kaii, one of the most prominent figures in postwar Nihonga. His practice was to begin with sketches of actual scenery from life, but to build these into solid and concise compositions free of unnecessary detail, resulting in lyrical landscape paintings that would resonate with any Japanese viewer as depictions of the country’s primordial scenery.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Gallery 4

* A space of about 250 square meters. This gallery offers cutting-edge thematic exhibitions from the Museum Collection, and special exhibitions featuring photographs or design.

The Challenges and Joys of Steel: David Smith’s Circle IV and Other Sculpture (June 18-September 26, 2021)

Room 11 Contemporary Craft Perspectives

In this room we present ceramics, metalwork, and lacquerware (in other words, works categorized as crafts according to this museum’s classifications) from the 1970s to the 2000s, drawn from the collection of the National Crafts Museum, which moved to Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture last October. They include pieces by Kuriki Tatsusuke and Hashimoto Masayuki, which resemble soft amorphous cells, and those by Araki Takako, Akiyama Yo, and Kofushiwaki Tsukasa, which evoke the passage of time in the manner of ancient, weathered artifacts. Some may wonder: can these really be called crafts? However, they are certainly made with sophisticated techniques displaying a high level of “craftsmanship.”

It is valid to say that in the decorative arts, clay, metal, or lacquer are more than the media used and are fundamental to the essence of the works. While the crafts of the early postwar period were characterized by tremendous enthusiasm for grappling directly with materials, the works shown here can be said to relativize relationships between the specific physical properties of materials and the artists who engage with them, and in these pieces we see a more distanced and objective creative process that appears to explore the very boundaries of the creative act. Contemporary crafts have developed in a way that illuminates these boundaries from the perspective of expanding them.

Room 12 Art of the Past 30 Years

So far, we have traced the history of modern Japanese art over the course of approximately 130 years. In this room, we present contemporary works from 1990 and later. Surveying the state of the world over the last three decades, we see that the Cold War came to a close only to have other conflicts over ethnicity and religion come to the forefront. Here in Japan, society has undergone a series of shocks including catastrophic earthquakes. Meanwhile, the development of information technology enabling instantaneous knowledge of global events has drastically changed the way we think about and perceive the world. In this era where information freely travels across national borders, the category of “Japanese art” may no longer even make sense, but nonetheless, art that addresses the realities of Japan’s society today should still be described as “contemporary Japanese art.” The artists featured here look intently at the world around them and powerfully represent what they see there, or ask questions of viewers that cause us to see the world in new ways.

About the Exhibition

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

May 25June 1–September 26, 2021 - Time

-

10:00-17:00 (Fridays and Saturdays open until 20:00)

*Last admission : 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

Mondays (except July 26, August 2, 9, 30 and September 20, 2021), June 17, August 10 and September 21, 2021

- Ticket

-

Advance ticket is recommended to avoid lines forming at the entrance.

Online purchase: 【e-tix】

Tickets can be purchased on site at the ticket counters, subject to their availability. - Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)

*The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

*Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

*Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

*Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID. - Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 17:00 on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Organized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo