Exhibitions

Feminism and the Moving Image (2024.9.3–12.22)

Date

-Location

Gallery 4 (2nd floor)

About

In the 1960s and 1970s, the media landscape drastically changed with the pervasive adoption of television and the emergence of video cameras, leading artists to integrate these new technologies into their work. Meanwhile, social activism gained momentum around the world, with major protest campaigns including such as the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements in the US. During this era, feminism emerged in the US as a mass movement with broad support, challenging the prevailing male-dominated social structure as an increasing number of women called for equality both in the workplace and at home. This environment spurred female artists to articulate the challenges and injustices they faced. In contrast to the predetermined subjects and forms of traditional painting, video was a relatively open and underexplored medium that proved effective in challenging societal norms and the one-sided portrayals common in the mass media. This exhibit showcases the development of moving-image works from the 1970s to today, presenting several key terms to aid appreciation of the works.

Key Term 1: The Mass Media and Images

In the 1960s and 1970s, TV came to fully pervade society, particularly in developed nations. Images distributed via the mass media significantly shaped perceptions of gender, i.e. socially and culturally constructed differences between the sexes. The media often propagated stereotypical gender roles, with women depicted as selfless and subservient housewives or mothers, and portrayals of masculinity and femininity reinforced and valorized heterosexuality.

Amid the hegemony of the mass media, video art emerged, capitalizing on video’s ability to directly appropriate and reconfigure the visuals and formats of TV programs, and thereby critically addressing problematic issues lurking beneath the media’s stereotypical imagery. For example, Martha Rosler parodied televised cooking shows to critique unpaid domestic labor and the patriarchy. Meanwhile, Dara Birnbaum spotlighted the objectification of women in the media by isolating scenes of female heroes in transformation, stripping these scenes of narrative content to show how they cater to the male gaze.

Key Term 2: The Personal

While 8mm and 16mm films require developing and printing after shooting, video does not require such processes. The immediacy of video led to the widespread staging of live performances that are shown on the spot as they are shot, as well as improvisatory filming practices. Video’s minimal gap between generation and completion of images allowed artists to engage with their images while shooting, resulting in works that incorporated everyday subjects and personal elements.

At the time when Martha Rosler produced Semiotics of the Kitchen, televised cooking shows featuring female chefs were popular in the US, and Rosler’s critique of the framing of cooking as “women’s work” may have been a minority viewpoint. Nonetheless, this work continues to resonate across national borders and eras. Idemitsu Mako’s Housewives and a Day records the chats of four women about how they spent the previous day, from waking up to going to bed. While their names are unknown and their faces unseen, their words point to the broader context of housewives’ circumstances, expanding their stories from personal anecdotes to broader social realities. A medium that directly conveys individual voices, video also serves to question societal norms.

Key Term 3: The Body and Identity

In the 1960s and 1970s, there was growing interest in the body in the arts, notably with the rise of performance art. Artists working with video explored the theme of the body extensively. Lynda Benglis and Joan Jonas filmed themselves and simultaneously displayed the footage on monitors, juxtaposing their physical bodies with their recorded images to underscore discrepancies between their actual selves and the mediated images. This approach suggested a departure from, or disruption of, conventional media portrayals of the “observed female body.”

From the 1970s onward, as daily life became saturated with countless disembodied images, art seeking to resurrect the realities of the body emerged. Having studied under the performance artist Marina Abramović, Shiota Chiharu created the video piece Bathroom focusing on her own identity. Shiota covered herself with mud, using the organic material in a performance intended to reconnect with raw somatic sensation amid the artificiality of urban life.

Key Term 4: Dialogue

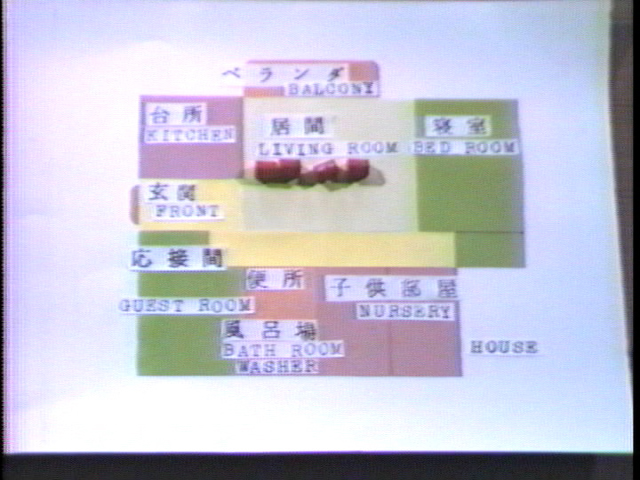

The medium of video introduced a verbal element absent from painting, sculpture, or photography. In Idemitsu Mako’s Housewives and a Day, four housewives gather around a h ouse’s floor plan and neighborhood maps discuss their daily routines. While there are four different people present, the scope and patterns of their behavior are astonishingly similar. In Love Condition by Endo Mai and Momose Aya, the two artists knead clay while engaging in a dialogue about “ideal genitalia.” Their differences of opinion and agreements lead to one twist and turn after another. Notably, in both of these works, dialogue unfolds not as a scripted scenario, but as spontaneous “chatting” including digressions, cross-talk, and laughter. Meanwhile, in Kimsooja’s A Needle Woman there is no spoken conversation, but we see a woman standing straight and immobile like a needle amid the hubbub of a city. Silent interactions between the woman and passersby who notice and gaze at her seem to represent unspoken dialogue between differing entities.

Hours & Admissions

- Location

-

Art Museum Gallery 4

- Date

-

September 3–December 22, 2024

- Closed

-

Mondays (except September 16, September 23, October 14, November 4) , September 17, September 24, October 15, November 5

- Time

-

10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 p.m.)

- Temporarily open on December 16 (10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.)

- Last admission: 30 minutes before closing.

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (¥400)

College and university students ¥250 (¥200)- The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

- Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holders.

- Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

- Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

- Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

- Including the admission fee for MOMAT Collection (4-2F).

- Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Free Admission Day

-

November 3 (Culture Day)

- Organaized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo