Exhibitions

MOMAT Collection(2025.2.11–6.15)

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

Highlights

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection!

To introduce some features of the museum’s exhibitions of works from the collection: First, its scale is one of the largest in Japan, displaying approximately 200 works each term from the museum’s holdings of over 13,000 works acquired since its opening in 1952. Also, it is one of the foremost exhibitions in Japan, tracing the arc of Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day through a series of 13 rooms, each with its own specific theme.

Some highlights of the current term are as follows. In Room 5 on the fourth floor, we present 100 Years of Surrealism, showcasing one of the most significant movements in 20th-century art through a selection of works from both Japan and abroad. During the first term, Room 10 on the third floor presents Spring Festival, with a lineup of works depicting spring flowers. In the second term, the same room will feature works by Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) painters who transcend meticulous rendering to probe deeper meanings. And in Gallery 4 on the second floor, Feminism and the Moving Image explores the works of female artists who addressed issues surrounding gender-related imbalances.

Once again this term, we are pleased to offer an extensive selection of works from the MOMAT Collection for your enjoyment.

Translated by Christopher Stephens

National Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection contains 18 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as National Important Cultural Properties. These include twelve Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following National Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Room1 Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Room10 Kawai Gyokudo, Parting Spring, 1916 (Exhibit Dates: February 11–April 13, 2025)

- Room10 Murakami Kagaku, Kiyohime at the Hidaka River, 1919 (Exhibit Dates: April 15–June15, 2025)

About the Sections

4F (Fourth floor)

A Room With a View

Located on the top floor of the museum, the rest area is furnished with Bertoia chairs, which can be compared to masterpieces of chair design. Please relax by the bright window. The large windows offer panoramic views of the greenery of the Imperial Palace and the Marunouchi skyline.

Information Section

Located in the introductory area, the Information Section presents a chronology of the MOMAT’s history, along with related materials. The materials on display are constantly being changed, so don’t miss them. The section also provides information on exhibitions at other museums that include works on loan from our museum, as well as a system for searching for works in our collection.

Room 1–5 1880s–1940s

From the Middle of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room1 Highlights

The MOMAT Collection exhibition of works from our permanent holdings features more than 200 items in a 3,000-square-meter space. The “Highlights” section of this exhibition features highly prized works of modern and contemporary art that showcase the strengths of our collection.

In the Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) area, during the first term (February 11–April 13) we present works by Kobayashi Kokei, Tsuchida Bakusen, and Suzuki Kimiko that evoke the arrival of spring. The second term (April 15–June 15) features works by Kawabata Ryushi that are a perfect fit for the season of fresh greenery.

Many of the Nihon-ga works featured here are quite decorative, with motifs such as kimono patterns and stylized plants. Similarly, in the oil painting section, we have brought together works in which figurative subjects are rendered decoratively, as well as those in which decorative elements develop toward the abstract. Please note the connections and contrasts between adjacent works as you enjoy these highlights from the museum’s collection.

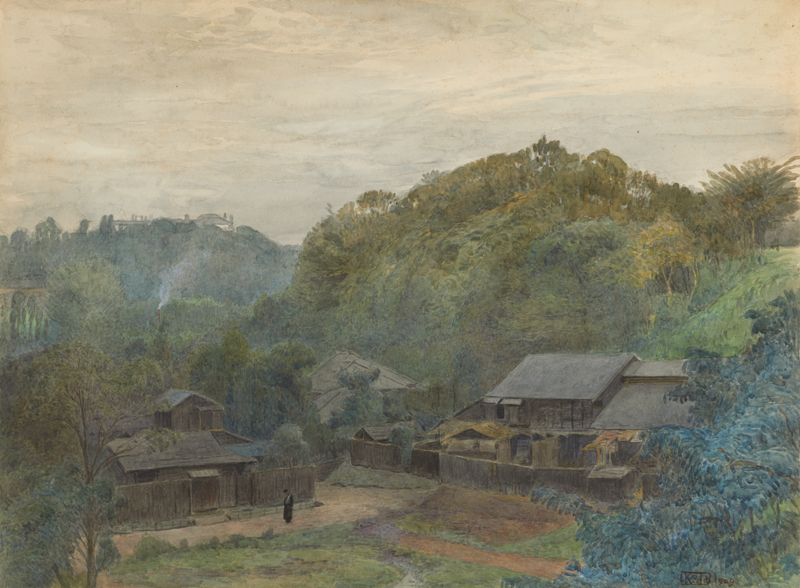

Room2 Discovery of Landscape

Last year, the museum received a generous donation of six watercolor paintings by Oda Kazuma.

In conjunction with their unveiling, Room 2 is dedicated to landscape paintings primarily from late in the Meiji era (1868–1912).

Traditionally, Japanese paintings and ukiyo-e prints of landscapes adhered to conceptualized and stylized images of scenery. However, in the late 19th century, the introduction of Western painting techniques and travel literature popularized a modern view of nature that involved depicting real scenes as they are. Artists began to travel around on their own and “discover” landscapes that were as yet unnamed. Under these circumstances, the introductory watercolor manual Handbook of Watercolor Paintings by Oshita Tojiro, published in 1901, became a bestseller, and watercolor painting was widely embraced by the general public as well. Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) also began to feature realistic landscapes based on in-person observation.

Oda, known for his prints of urban scenes, took up watercolor painting early in his career under the influence of his predecessors. His paintings primarily focus on natural landscapes around Tokyo, but works such as Near Takadanobaba hint at the interest in urban landscape that would characterize his later prints.

Room3 Lyricism and Decadence

Early in the Taisho era (1912–1926), the painter Hada Teruo, who had moved from Kyoto to Tokyo, wrote in his diary about his close friend Tobari Kogan: “When he came to see my first exhibition in Tokyo, we found ourselves chatting and laughing, and since then he, the romanticist, and I, the decadent one, have become oddly close.” The references to romanticism and decadence in Hada’s recollection capture the mood of the times in which they lived. Both men were devotees of the Asakusa area. At that time, Asakusa was home to a vibrant entertainment district beneath the observation tower Ryounkaku, commonly known as Asakusa Junikai (junikai indicating the building’s twelve stories, which made it extremely tall for the time). This was the liveliest district in Tokyo, bustling with theaters large and small, troupes of acrobats, and cinemas, and the painters felt a profound connection with the marginalized denizens of this community and depict them. However, after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 caused the collapse of Ryounkaku, there was a migration to new entertainment districts such as Ginza and Shinjuku. Here we present works that not only convey the shifting fortunes of Tokyo’s amusement quarters, but also embody the lyricism and decadence that characterize the Taisho era.

Room4 Shapes of Modernism: Sculptures from the 1920s and 1930s

In Japan, the 1920s and 1930s, between the end of World War I and the outbreak of World War II, were a time when artists engaged in wide-ranging explorations without being confined by traditional aesthetic standards. In sculpture, there was a notable departure from Rodin-inspired expressions of emotion and vitality in favor of bold distortions and simplified forms.

This era was also characterized by the implementation of urban planning policies in 1920 in major cities such as Osaka and Tokyo. Urbanization progressed rapidly, aided by reconstruction efforts following the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Western influences permeated everyday life, and culture was increasingly democratized. In tandem with this modern urban culture, there emerged diverse forms of sculpture that intersected with architecture, crafts, and design. This trend is exemplified by the works of Yo Kanji and Ogishima Yasuji, who were active in Kozosha (Construction Group) and championed practical applications of their art under the slogan “socialization of sculpture.”

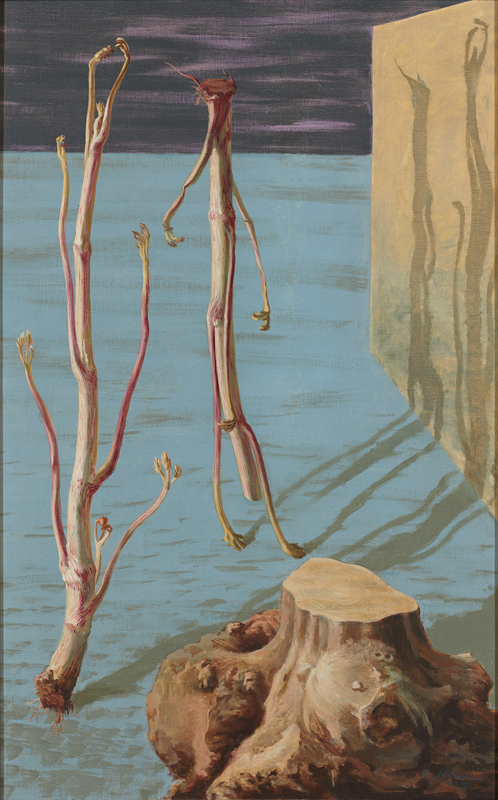

Room5 Surrealism 100th Anniversary

This year marks the centenary of publication of the Surrealist Manifesto by French poet André Breton (1896–1966). Surrealism, one of the 20th century’s major artistic movements, eschewed rationality and explored the realms of the irrational and the unconscious. With roots in the Dada movement that emerged during World War I, Paris-based Surrealism soared to international prominence and influenced various art forms over the course of many years. In Japan, the Surrealism and its ideas were introduced early on by the critic and poet Takiguchi Shuzo (1903–1979) and the Western-style painter Fukuzawa Ichiro (1898–1992), among others. During World War II, some Surrealists persecuted by the Nazi regime fled to the US, where they continued their activities and impacted postwar American art. This room traces Surrealism’s path and its spread to Japan and the US, beginning with works by prominent Surrealists Max Ernst (1891–1976), and Yves Tanguy (1900–1955), alongside various historical materials.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s–1960s From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 Painting the Other

In war, there is always an “other side.” During wartime, how do people perceive others from enemy nations? During World War II, Japanese artists produced paintings that were intended to bolster war morale and were shown at various exhibitions. In the War Record Paintings housed in this museum, the enemy is often conspicuously absent, and the focus is on valiant depictions of Japanese soldiers in battle. Such portrayals effectively render the suffering and wounded bodies of enemy combatants invisible. However, there are exceptions, and some War Record Paintings depict military personnel from the Allied forces, including the US, the UK, and Netherlands.

By portraying scenes of the defeat of these “Western powers,” artists sought to affirm the superiority of Japanese forces. Nuances of composition, character portrayal, and color usage in the works in this room reveal the artists’ endeavors to differentiate the two sides. After the war, the Japanese military’s acts of brutality, persecution, and inhumane treatment of prisoners were adjudicated as war crimes at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (also known as the Tokyo Trial) and the Class B and C War Crimes Trial. While aspects of these works undoubtedly appear inappropriate from today’s perspective, we exhibit them to illustrate how Japanese artists during wartime portrayed the military forces of the Allied countries.

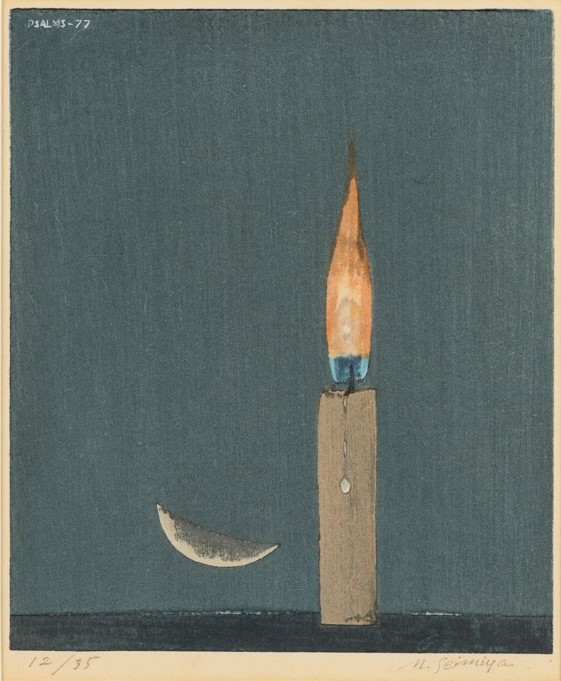

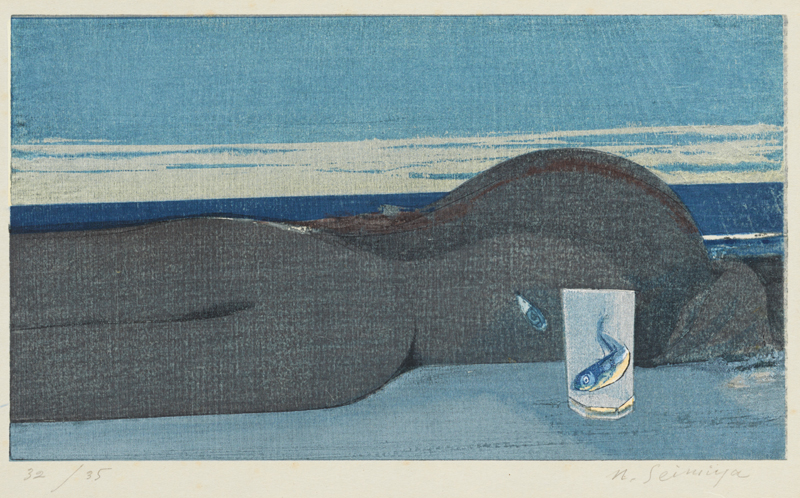

Room7 Seimiya Naobumi

Seimiya Naobumi, one of Japan’s foremost woodblock printmakers, began working in the medium in the 1950s. After postwar reconstruction, and amid Japan’s period of rapid economic growth, use of experimental print techniques was widespread. However, Seimiya distanced himself from these trends, pursuing delicate woodblock prints brimming with a feeling of transparency. For the artist, printmaking was not merely a duplicative technology.

For each individual print, he carefully adjusted the colors and printing pressure, and the spirit of dedication with which he printed each layer comes through in the work. His richly poetic and introspective images continue to captivate many viewers.

In this room, alongside Seimiya’s important works from the 1970s which we acquired last year, we present works by his contemporary and close friend Komai Tetsuro, his great admirer Oka Shikanosuke, and long-standing associates Wakita Kazu and Nomiyama Gyoji. Please enjoy these alongside great works by Paul Klee, Ben Nicholson, and Onchi Koshiro, who all significantly influenced Seimiya.

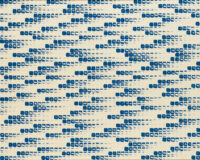

Room8 Effects of Repetition

Before coming here from Room 7, did you have the chance to see Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #769 (1994) in the “Room to Consider the Building”? That work is characterized by rhythms generated through repetition and slight shifting of geometric shapes, creating effects like those of minimal music. In connection with LeWitt’s work, Room 8 features works from the 1960s and 1970s with repetitive structures.

During these decades, works emerged that challenged traditional frameworks of painting as a means of imagistic expression by filling the entire surface with repetitions of the same pattern. While systematic repetition conveys an inorganic impression, closer examination of slight deviations and differences evokes the physicality of the artist engaged in these repeated actions.

In printmaking, the adaptation of silkscreen (originally a commercial technique) to fine art led to works that reiterated the same images. These works, which interrogate the very process of how we perceive, align closely with the deluge of images in the information-saturated society of their time.

Room9 Suda Issei, Fushi Kaden (February 11–April 13, 2025)

Fushi Kaden is a series that was irregularly serialized in eight parts in Camera Mainichi magazine between December 1975 and December 1977. In 1978, it was compiled in a photo book. It is known as the work that established Suda Issei’s reputation, including his receiving the Photographic Society of Japan Awards Newcomer’s Award in 1976 while the series was in progress.

The scenes of traditional festivals that appear prominently throughout the works were shot in various parts of Japan, including the Kanto, Hokuriku, and Tohoku regions. In other words, this is also a photographic record of Suda’s journey. Both journeys and festivals lie outside the usual bounds of time and space. Does this mean the world depicted in Fushi Kaden is an extraordinary realm of space-time? In fact, the photographer stated that from his earliest years, his subject was consistently “the ordinary.” He wrote in the photo book Ningen no Kioku (Human Memories), “The most humdrum scenes of everyday life are, for me, brimming over with tensions.” Whether traveling or at home in his own neighborhood, he sought out and responded to the same kinds of scenes and captured them on film.

The title in drawn from Fushi Kaden (which has a range of translations including “Transmission of the Flower of Performance”), an early 15th-century treatise on Noh theater by the actor and theorist Zeami.

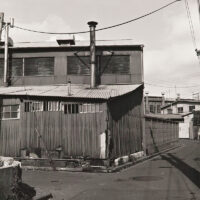

Room9 Watanabe Kanendo, Streets Already Seen (April 15–June 15, 2025)

Streets Already Seen was first released in 1980 in a book of the same title, comprising a novel by Kanai Mieko and photographs by Watanabe Kanendo. The following year, Watanabe held a solo exhibition of these works and won the Kimura Ihei Award.

This work, primarily shot in Tokyo and its suburbs, represents a departure from the dramatized feel of Watanabe’s earlier works, adhering to quiet, matter-of-fact depiction of material things. Nonetheless, the urban scenes he captured are imbued with an enigmatic quality.

The novelist Abe Kobo, one of the judges for the Kimura Ihei Award, commented: “Every scene is strangely overcharged, as if sparks would prick one’s eyeballs if the works were viewed too closely. While the physiology of observing the ordinary is nonchalantly maintained, his camera clearly captures the cracks and holes through which the extraordinary seeps.”

The title itself is enigmatic. Does “already seen” imply that the photographer himself has seen these scenes before, or that wherever the lens is directed, it captures something that someone has “seen before”? With regard to this series, Watanabe acknowledged the influence of Eugène Atget, who continually photographed the streets of Paris in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Room 10 Arp’s Studio /Spring Festival (February 11–April 13, 2025)

Photo:Rüdiger Lubricht, Worpswede

©Stiftung Jean Arp und Sophie Taeuber-Arp e.V.

In the area at the front, we present plasters made in the process of sculpting by Jean (Hans) Arp (1886–1966). Born in Strasbourg, France, and active in Paris and Switzerland from the early 20th century onward, Arp is known for sculptures with biomorphic forms occupying a liminal space between abstract and figurative. Here, we trace the evolution of these sculptural forms through the plasters that were a crucial stage in Arp’s exploration of new forms.

In the room at the rear, we are pleased to bring you our annual Spring Festival, for which we have brought together a number of works featuring flowers to mark the season. We hope you relax and enjoy spring while seated on Kenmochi Isamu’s rattan stools and Seike Kiyoshi’s mobile tatami mats. Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring (Important Cultural Property), a frequent staple of the Spring Festival, is exhibited in this room. It depicts cherry blossoms along the waterside swiftly scattering in a scene that recalls Chidorigafuchi (a famous cherry blossom site, walking distance from here). Over 40 types of cherry trees are also on view in Atomi Gyokushi’s Scroll of Cherry Blossoms, and some of these may also be found among the many varieties blooming along the street in front of the museum.

Room10 Arp’s Studio /Beyond the Visible (April 15–June 15, 2025)

Photo:Rüdiger Lubricht, Worpswede

©Stiftung Jean Arp und Sophie Taeuber-Arp e.V.

In the area at the front, we present plasters made in the process of sculpting by Jean (Hans) Arp (1886–1966). Born in Strasbourg, France, and active in Paris and Switzerland from the early 20th century onward, Arp is known for sculptures with biomorphic forms occupying a liminal space between abstract and figurative. Here, we trace the evolution of these sculptural forms through the plasters that were a crucial stage in Arp’s exploration of new forms.

In the rear area with glass cases are works from our collection by three Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) painters: Hayami Gyoshu, Murakami Kagaku, and Tokuoka Shinsen. Theseartists all pursued highly detailed realism for a time during the Taisho era (1912–1926). They strove to capture the essence of transcendent presence within the bounds of reality, and after moving away from precise figurative rendering, adopted alternative methods of symbolic representation. Their endeavors can be seen as coinciding with the mentality, prevalent in the1910s, of seeking elemental mystery within the physical realm.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11–12 1970s–2020s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Room11 (Im)balance

In 2022, the museum carried out conservation work on Endo Toshikatsu’s Trieb–Modernity–Body. We have compiled a report on the project, and in conjunction with this, here we present works that relate to the distinctive use of water in Endo’s sculpture.

It is common practice for museums to prohibit food and beverages, and this is to prevent the risk of mold and pests that could interfere with conservation of the artworks. To preserve balance over the long term, museums remove elements that cause imbalance. However, the ever-changing natural landscape, water, and other fluids have always been a source of inspiration for artists, and many artists embrace the challenge of inducing unstable movement within their works while maintaining an appearance of stillness. The works shown in this room, all notable manifestations of this intent, are by Anthony Caro, who creates the impression of iron sliding off its pedestal; Ikemura Leiko and Maruyama Naofumi, painters who make extensive use of staining techniques; and Endo Toshikatsu, who employs water itself as a material. The pursuit of instability at times pushes the boundaries of the museum’s basic policy of handling only stable works and materials.

Room12 Artists and Dark Tourism

The works presented here date from the 1990s or later. Surveying works from the 1990s in particular, one finds that many deal with dark aspects of society, and war is a frequent subject. It was a time marked by a series of major events that profoundly impacted global society: the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the outbreak of the Gulf War and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the widespread adoption of the internet. In Japan, notable events included the transition from the Showa to the Heisei era in 1989, the bursting of the economic bubble in the early 1990s, and the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and Tokyo subway sarin attack in 1995. Artists’ shared concerns with dark themes can be viewed as a response to, or manifestation of, a general apocalyptic mood pervading society. However, their perspectives were not necessarily pessimistic. As indicated by the popularity of the term “postmodern” at the time, there was also a sense of hope that these upheavals could provide opportunities to move beyond conventional views of modern history that presumed linear forward progress. It was also a time when Japanese artists who boldly incorporated elements of toys and animation began gaining high international acclaim.

Hours & Admissions

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

February 11–June15, 2025

- Closed

-

Mondays (except February 24, March 31, May 5), February 25, May 7

- Time

-

10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 p.m.)

- Last admission: 30 minutes before closing.

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)- The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

- Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

- Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

- Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

- Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

- Including the admission fee for Feminism and the Moving Image (Gallery 4)

- Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Free Admission Day

-

May 18 (International Museum Day)

- Organaized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo