Exhibitions

MOMAT Collection(2023.3.17–5.14)

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

The collection exhibition from October 12, 2022 to February 5, 2023

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection! The museum opened on December 1, 1952, and will celebrate its 70th anniversary during the current term (October 12, 2022 – February 5, 2023).

To briefly introduce some features of the museum’s exhibitions of works from the collection: First, its scale is one of the largest in Japan, displaying approximately 200 works from the museum’s holdings of over 13,000 works collected over the course of 70 years. Furthermore, it is the only exhibition of its kind in Japan, tracing the arc of Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day through a series of 12 rooms, each with its own specific theme.

A highlight of this term is Playback: The Abstraction and Fantasy Exhibition (1953–1954), on view in Rooms 7 and 8 on the 3rd floor on the occasion of the museum’s 70th anniversary. It is a challenging project that utilizes VR and other technologies to recreate an exhibition that marked the museum’s first anniversary. Also on the 3rd floor, in Room 9, is Gifts, which showcases distinctive works donated during the museum’s 70-year history of art acquisitions.

Our hope is that as you view the exhibition, you will sense the depth and breadth of the museum’s 70 years of activities, as well as the ways in which art has evolved over the past century.

Translated by Christopher Stephens

Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 15 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as Important Cultural Properties. These include nine Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Wada Sanzo, South Wind, 1907

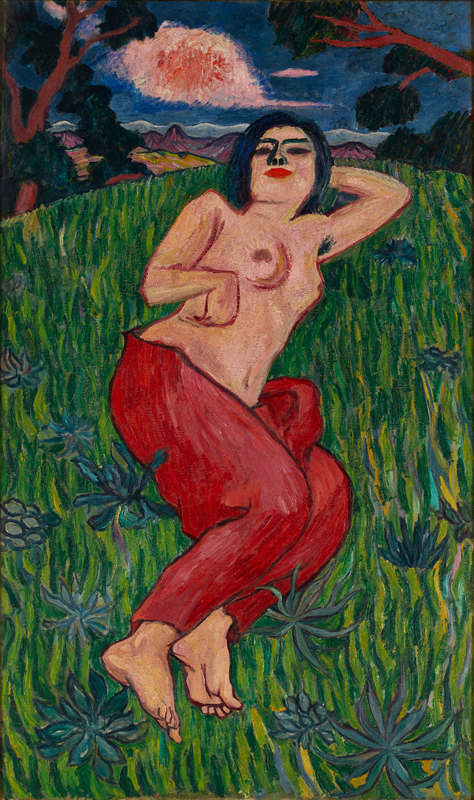

- Yorozu Tetsugoro, Nude Beauty, 1912

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915

- Please visit the Important Cultural Property section Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F (Fourth floor)

Room 1– 5 1880s-1940s

From the Middle of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

A Room With A View

Reference Corner is currently out of service.

Room 1 Where Do We Draw the Line?

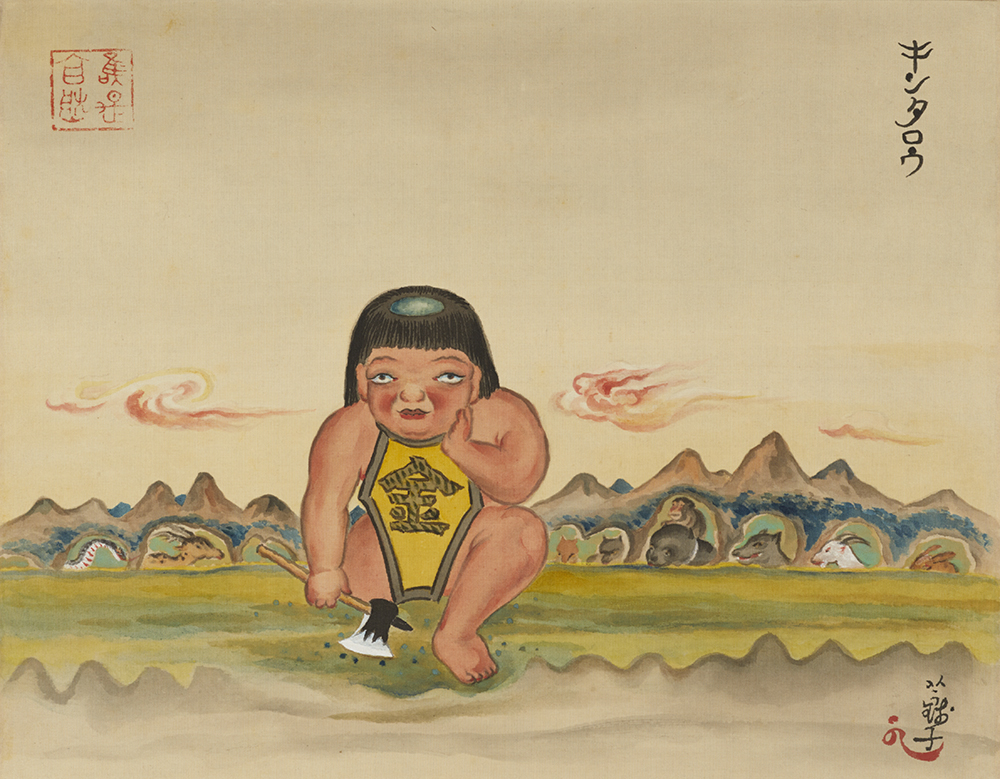

Room 1 is usually dedicated to “Highlights,” works that are representative of the museum’s collection, but for this term we have incorporated, like the other rooms, into a program that traces the evolution of modern and contemporary art in Japan. In this room, which kicks off the historical overview, we present works produced from the mid-1880s through the early 1910s.

This approximately 30-year period began about 20 years after the end of the Edo Period (1603–1868). These years saw the state of Japanese art change drastically. At the time, many artists sought to bring Japanese art into a new era by combining European standards and homegrown originality in a balanced manner. How should the two be blended? The search for answers plunged them into an all-encompassing process of trial and error. In the results we see the old and the new, confusion of subject matter, mismatch of subject and style, and as-yet-unmastered technique. To present-day viewers who are familiar with subsequent “modern-looking” modern art, their endeavors can be both bizarre and intriguing, but where do we draw the line between that time and our own? With this question in mind, please enjoy this journey into the formation of modern art in Japan.

Room 2 Stargazers

The title “Stargazers” can also refer not only to people gazing up at the night sky, but also to astronomers or astrologers.

For us, this title has dual significance. First, it refers to the expanding self-awareness and ambition of individual artists, as if he or she were seeking to become a star. To this end, it is best if they engage with truths that only they can see, and are as personal as possible in subject matter and style. In the 1910s and 1920s, the vision of art conveyed by magazines such as Shirakaba (White Birch) swiftly turned the young people of the time toward self-expression. Artists such as Sekine Shoji and Kaita Murayama were truly the stars of that era.

Another implication of the title is that of celestial bodies as subjects. In the works of Kishida Ryusei, Yorozu Tetsugoro, and Kawabata Ryushi (on view through December 4), the earth and the sun are represented as mysterious sources energy that generates life. Also, art as self-expression was the foundation for the avant-garde Expressionist and Futurist movements that emerged in Europe, and some of the works of Otake Chikuha (on view from December 6), who was inspired by Futurism, are on the theme of space and heavenly bodies.

Room 3 Deconstruction and Reconstruction

The period between the two world wars was one when new art forms that sought to transcend established concepts and frameworks emerged one after another. For example, many works endeavored to deconstruct and reconstruct images by fragmenting and transforming the subjects and rendering them abstract, or by incorporating fragments of materials that originally had a different function, such as newspaper or wallpaper, into the picture (examples can be seen in works by Murayama Tomoyoshi and Kurt Schwitters). Meanwhile, another intriguing aspect of this period was a growing concern with the primitive and universal, a yearning for simplicity and primitiveness, and the rediscovery of classical antiquity, which appears on the surface to be opposed to the avant-garde impulse (as in the works of Fernand Léger and Togo Seiji).

Underlying these explorations, the depth of the wounds inflicted on the world by World War I and mounting anxiety about the next war can be glimpsed. This room introduces works from the interwar period by artists who, while responding sensitively to art movements such as Cubism and Surrealism, sought to establish their own modes of expression.

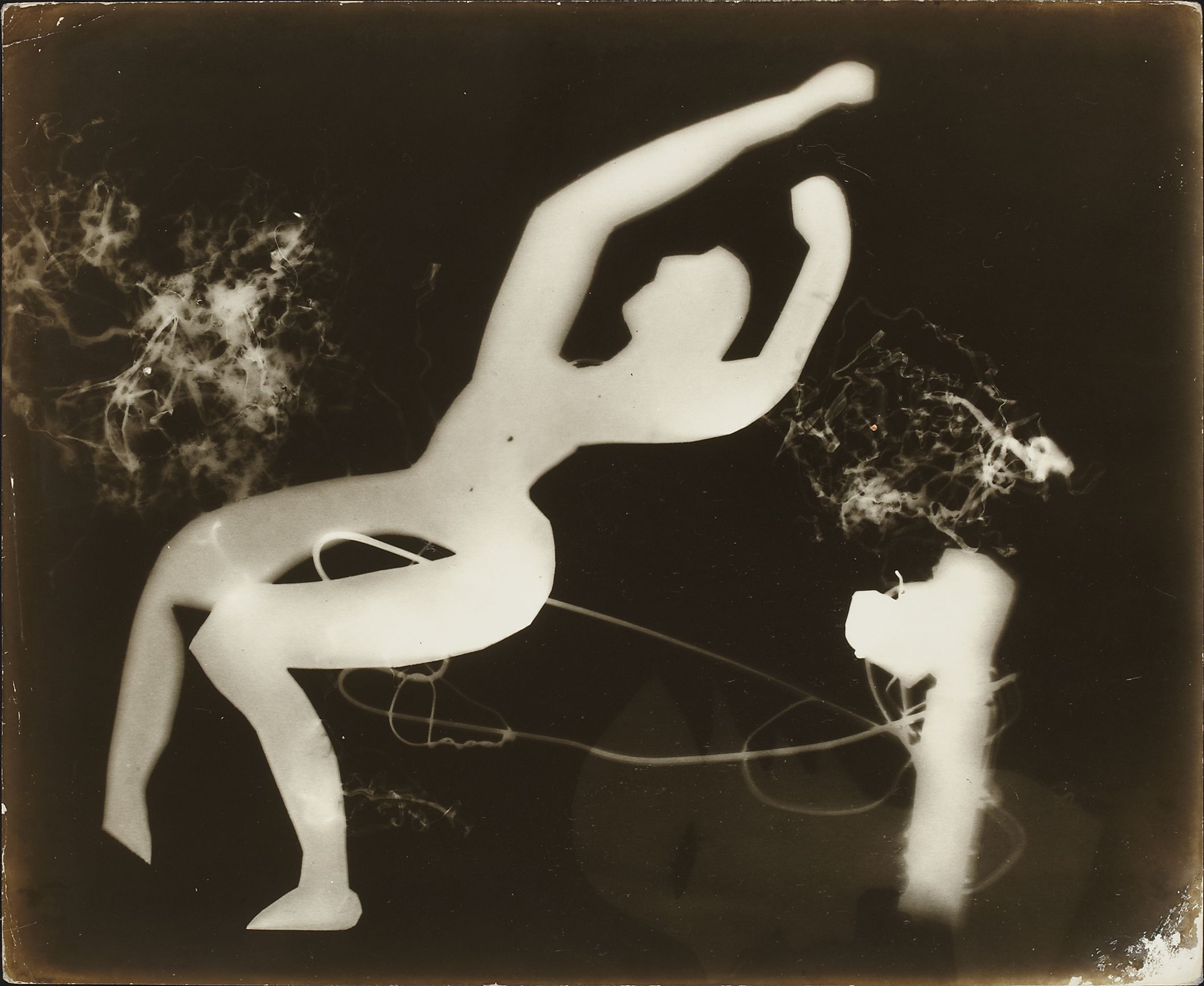

Room 4 EI-KYU: Drawings / Photographic Paper / Material Texture

The exhibit focuses on Reason of Sleep, the debut work by Ei-Kyu, an artist known for diverse works including oil paintings, collages, and prints, as well as his drawings and photo-dessin (“photo-drawings”) from the same period.

After withdrawing from the Western Painting Department of the Japan School of Art, Ei-Kyu, who had been exploring his own approach to art by submitting works to public open-call exhibitions and writing art criticism, became interested in photography around 1930. At the time, Japanese photographic expression was in the midst of a transition from pictorialism to shinko shashin (New Photography), which aimed for artistry unique to photography. After encountering photograms, in which objects are placed on photographic paper and exposed to light, Ei-Kyu began drawing with light, with photographic paper as a new kind of drawing paper. Pictorial elements he used as a painter, such as stencils and celluloid drawings, were synthesized with the smooth material texture of photographic paper to create unique images distinct from both photography and painting. Ei-Kyu called these works photo-dessin (dessin is the French word for “drawing”). His aspiration toward free expression unconfined by existing values can be seen in the freely metamorphosing lines and shapes of his drawings.

Room 5 Perspectives on American Society

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the US saw the emergence of many photographs and paintings that documented scenes of urban and rural life and focused on the realities of society. In particular, photographs that clearly captured the changing times became a crucial medium that helped people understand the current situation and steered the government toward the policies of the New Deal, which provided wide-ranging support to impoverished workers and people in need. However, some foreign workers were excluded from state relief measures, including Japanese painters who continued to work there.

In the 1940s, the US economy began to recover due to a booming military industry associated with World War II. At the same time, the war deepened rifts that divided citizens. In 1942, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the government decided to relocate Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to internment camps. Photographers and painters showed their feelings toward this discriminatory policy by documenting the reality of the situation.

The works of Japanese American artists who have explored the history of inclusion and exclusion of citizens amid this turbulent society, especially from the standpoint of racial minorities, have left a unique mark on the intertwined art histories of the US and Japan.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s

From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 The War Years: Focus on Restored War Record Paintings

After the National Mobilization Law of 1938 called on all Japanese citizens to join in the war effort, artists were compelled to document the conflict in War Record Paintings. After the war’s end, the US-led Allied Powers requisitioned the 153 major works in this genre that survived, and transferred them to the United States in 1951. However, requests from Japan for their return eventually paid off, and in March 1970, the two countries finally agreed that the paintings would be repatriated on “indefinite loan” from the US government to the Japanese government.

Depending on the degree of damage, restoration work was carried out, but as traces of these restorations were becoming increasingly noticeable due to deterioration over time and other factors, new restorations were carried out and the frames replaced in recent years. This part of the Collection exhibition features art from the World War II years, with a focus on the restored War Record Paintings.

One highlight of this section is the evolution of Fujita Tsuguharu’s artistic concerns as the war progressed, from his remarkably colorful yet pale-hued early War Record Paintings, in which battle scenes unfolding amid vast landscapes took precedence over individual human figures, to the sepia-toned vistas of battle to the death, with figures intricately entangled, as the war neared its end.

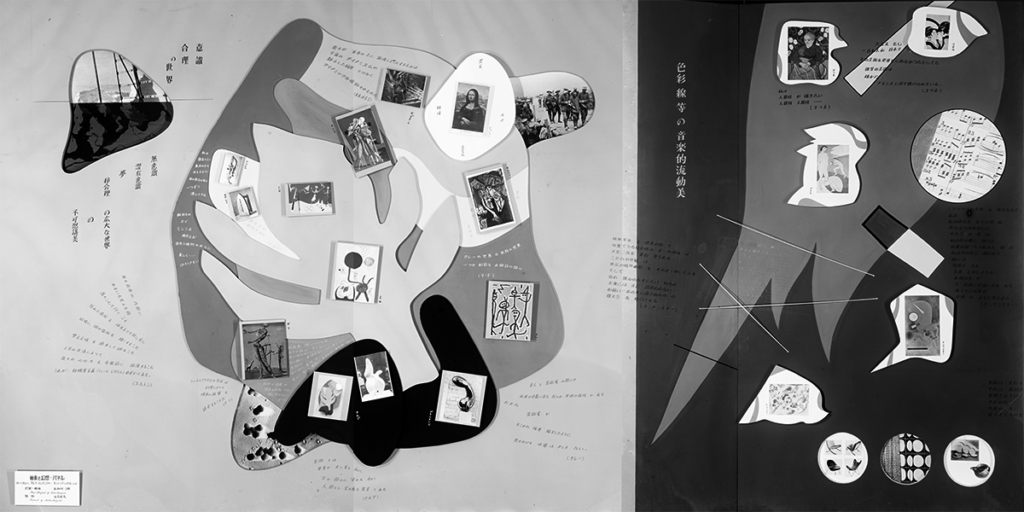

Room 7 Playback: The Abstraction and Fantasy Exhibition (1953–1954) (1)

1953年.jpg)

This museum opened in Kyobashi, Tokyo on December 1, 1952, the year Japan regained its sovereignty following the postwar occupation. This section focuses on one of our important early exhibitions, Abstraction and Fantasy: How to Understand Non-figurative (Non-realistic) Painting (December 1, 1953 – January 20, 1954), with videos and documents looking back on the museum’s early years.

After opening with the inaugural exhibition Modern Japanese Art: Retrospective and Perspective of Modern Painting, the museum marked its first anniversary with the Abstraction and Fantasy exhibition, a new experiment in presenting works by contemporary artists on a specific theme, as opposed to the traditional practice of displaying well-known works side by side.

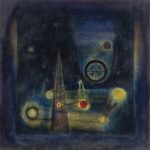

With the art critics Uemura Takachiyo and Takiguchi Shuzo as cooperating committee members, the exhibition was organized around two major trends in modern art, abstract art and Surrealism (or Fantastic Art). What were its contents like? In Room 7, visitors can experience a VR projection based on archival materials and records. Please take this opportunity to relive the innovative practices of the museum’s early days.

Room 8 Playback: The Abstraction and Fantasy Exhibition (1953–1954) (2)

In Room 8 we present works from the Abstraction and Fantasy: How to Understand Non figurative (Non-realistic) Painting exhibition, as well as works from the 1950s by artists featured in that exhibition. Fourteen of the works in the Abstraction and Fantasy exhibition are now in the museum’s collection: Kitadai Shozo’s Mobile Object (Composition of Rotating Surfaces) (1953), Kawaguchi Kigai’s Strange Shadow (1953), Furusawa Iwami’s Pluto’s Daughter (1951), Kawara On’s Bathroom 16 (1953), six photocollages by Okanoue Toshiko, Shinagawa Takumi’s Rond (Endless Dance) (1953), Hamada Chimei’s Elegy for a New Conscript: Sentinel (1951, first shown with the title Landscape), Komai Tetsuro’s Memory (1948, first shown with the title The Reminiscence of the Okhotsk Sea), and Ei-Kyu’s Signal (1953, first shown with the title Evening Twilight).

Please compare the VR reproductions of the seven rooms with actual paintings exhibited. The year 1953 also coincides with the period when reportage paintings by Kikuji Yamashita and others began to be exhibited at the 1st Nippon Exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. We hope this exhibition will provide opportunities to look back on the art of the 1950s through the activities of what was then our newly opened museum.

Room 9 (First half: October 12–December 4, 2022)

Gifts: Stieglitz, Shigeta, B. Weston and Farkas

This year, as the museum celebrates its 70th anniversary, we are reflecting on the museum’s history as we present works from the photography collection. This term we focus on gifts, i.e. donated works.

Alfred Stieglitz, known as the “father of modern photography,” was a photographer who worked tirelessly to establish photography as a modern artistic medium. Harry K. Shigeta (Shigeta Kinji) was born in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, and emigrated to the US, where he achieved success in both artistic and commercial photography. Brett Weston, based on the American West Coast, is known for belonging to a family of photographers, including his father Edward and his brothers. The works of these three photographers were donated to the museum by the artists or their bereaved families before the museum began acquiring photographs on an ongoing basis in 1990, and represent the dawn of the museum’s photography collection. The works of Thomaz Farkas, one of Brazil’s best-known photographers, were donated to the museum in recent years.

Our collection of photographs, which now numbers over 3,000, includes many of these donated works. They are “gifts” for everyone who encounters them in the galleries.

Room 9 (Second half: December 6, 2022–February 5, 2023)

Gifts: The Kurenboh Collection

The Kurenboh Collection is a group of 110 works by 60 artists from outside Japan, which were gifted to the museum in two separate donations in FY2014 and FY2016. This exhibit features 17 of these works, which provide an overview of the evolution of American photography from the mid-20th century to the present day.

The donor, Taniguchi Akiyoshi, has been collecting photographs for many years while serving as the head priest of a Buddhist temple in Kuramae, Tokyo. After the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011, he donated his collection of works by Japanese photographers to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and his collection of works from overseas to this museum.

Taniguchi, who studied photography in New York for five years beginning in 1979, says he has learned a great deal from interacting with photographic works. In 2006, he opened a small space, known as Kurenboh, on the grounds of his temple for people to encounter works and meditate. The Kurenboh Collection is a “gift” imbued with hope that the experience of interacting with art will open up to many more people.

Room 10 (First half: October 12–December 4, 2022)

Creating Depth

How does an artist create a sense of depth on a two-dimensional surface? The best-known method is perspective, a method that builds on the visual phenomenon of two parallel lines appearing to come closer together as they recede into the distance. There are three types – one-point, two-point, and three-point perspective – as well as aerial perspective and chromatic perspective. Aerial perspective reduces the contrast of objects that are farther away, while chromatic perspective gives distant objects (in many cases) a bluish tint. Another effective method is to superimpose subjects, taking advantage of the fact that a partially hidden subject is perceived to be more distant than the subject that overlaps it. There are other approaches as well, such as placing nearby objects at the bottom of the picture and faraway objects at the top, in accordance with a convention that has been shared in Oriental painting since ancient times, and the so-called san-yuan (atmospheric perspective) method, which originated in Chinese landscape painting.

Takeuchi Seiho’s Day Labor is characterized by its multi-layered motifs. The work is presented for the first time in this exhibit, which also features a special section on expression of depth in modern and contemporary Japanese-style painting. We hope you enjoy the techniques and effects used in each of these works, from complex, composite approaches to works that intentionally ignore perspective altogether.

Room 10 (Second half: December 6, 2022–February 5, 2023)

Gifts: Donations from Collectors / The Pan-Real Art Association

In conjunction with Room 9, which features photography, the exhibit in this room is also focused on donated works, with the title Gifts. Please proceed directly from the case of nine sketchbooks immediately on the left to the area with glass cases.

The museum’s Nihon-ga (modern Japanese-style painting) collection currently numbers 857 works. Of these, approximately 35% were donated or bequeathed to the museum (with the remainder consisting of 45% that were transferred to the museum’s administration and 20% that were purchased). Once a work is housed in a museum, the relationship between the work and its previous owner tends to be obscured, but when a certain collector donates a large number of works, there are often related anecdotes that should not be overlooked. This section introduces just a few of these cases, which we are pleased to present, with gratitude to the donors.

In the space just in front of you are works by painters belonging to the Pan-Real Art Association. After World War II, these artists confronted questions about what Nihonga can be, and took up the challenge of creating new and innovative paintings.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Gallery 4

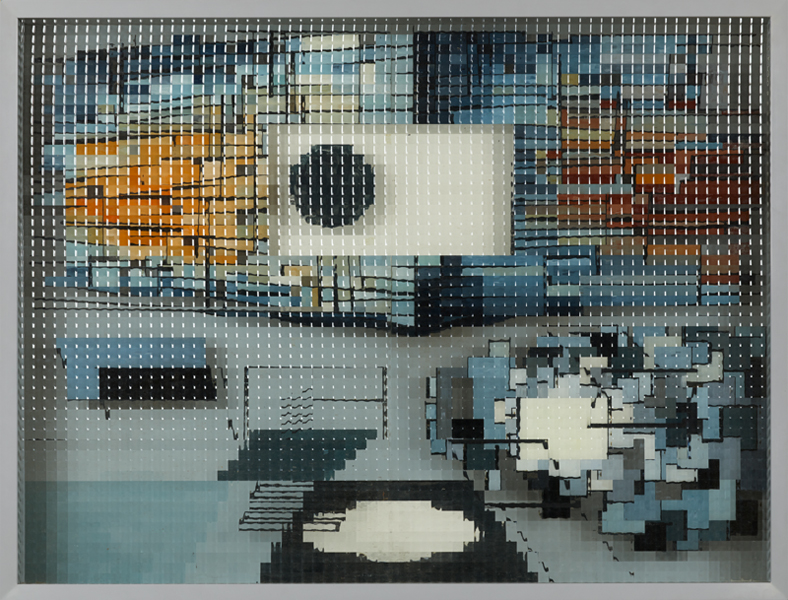

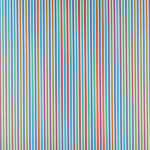

Room 11 Paintings as Objects and Places

The works of both Lucio Fontana and Motonaga Sadamasa, which involve slashing or pouring paint on canvases, are prime examples of a 1950s and 1960s painting trend toward emphasizing the physical presence of the canvas, while at the same time treating it as a place where vestiges of actions are preserved. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was a growing movement toward painting as space in which colors and motifs appear, relying on the materiality of the canvas itself, rather than on three-dimensional illusionism or representation of some kind of image. Repetition of colors and motifs with slight variations shows an ascetic and reductionist tendency.

Spatialism, Gutai, Color Field Painting, Minimalism, Optical Art, Supports/Surfaces, Mono-ha–there are various names for movements that emerged during this period, but when the works are viewed side by side, we can see commonalities in terms of the artists’ conceptions of painting and approaches used to realize their ideas.

Room 12 New Faces of the 1980s

The 1980s was a turning point in postwar Japanese history in both socioeconomic and cultural terms, and a series of phenomena underpinned by new values emerged, as symbolized by such terms as “new academicism,” “new music,” and “new painting.” In an era when advertising and magazine culture was blossoming, contemporary philosophy was in vogue, and subcultures were flourishing, new modes of expression appeared in the art world, including works incorporating images from popular culture and installations that deployed works in spaces.

Ohtake Shinro, whose solo show is held in the Special Exhibition Gallery (opening November 1), is among the artists who rose to prominence in that era. Here we present works from the museum’s collection by artists who, like Ohtake, began their careers while still young in the 1980s. Reaction against the Conceptualism and Minimalism of the 1970s led many of these artists to turn toward more traditional genres such as painting and sculpture.

About the Exhibition

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

October 12, 2022—February 5, 2023

- Time

-

10:00 AM—5:00 PM (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 PM)

*Last admission: 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

Mondays (except January 2 and 9), December28—January 1, and January 10

- Ticket

-

Online ticket is recommended to avoid lines forming at the entrance.

Online purchase: 【e-tix】

Tickets can be purchased on site at the ticket counters, subject to their availability. - Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)

*The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

*Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

*Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

*Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID. - Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 PM on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Organized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo