Watch, Read, Listen

Newsletter of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Exhibition Review “The Tangible” and “the Intangible”

Back

What is an Intangible Cultural Property? According to the 1950 Act on the Protection of Cultural Properties, it is defined as “theater, music, craft skills, and other intangible cultural properties that possess high historical or artistic value to our nation” (Article 2, paragraph (1)). The term “cultural properties” is generally associated with tangible items, such as architecture or artwork. Intangible cultural properties, on the other hand, are techniques that have no form. This act was one of the earliest in the world to stipulate the necessity of the preservation and inheritance of these intangible subjects as “cultural properties” by law. It is no exaggeration to call this one of the proudest decisions in our nation’s history of cultural property protection.

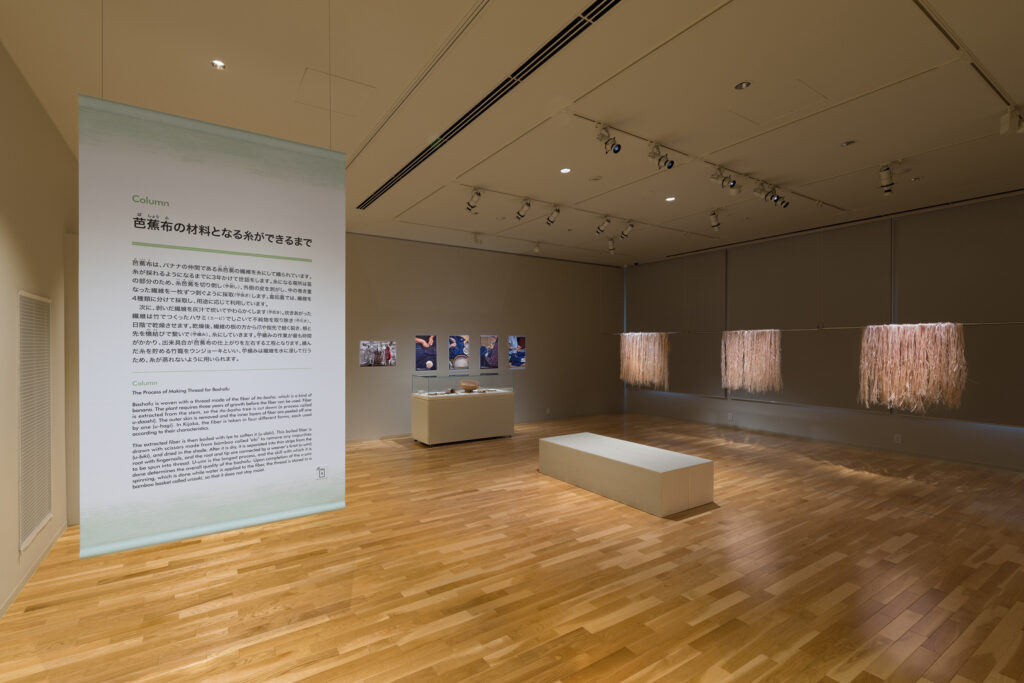

Attention to intangible cultural properties can be found throughout this exhibition. It is evidently demonstrated in the video footage introducing the production process of bashofu, and in the exhibition of raw materials and tools for thread production. Regarding the former, a short version of the 2014 video produced by the Agency for Cultural Affairs (ACA), titled “Bashofu: The Art of Taira Toshiko”, welcomes the visitors as an introduction at the entrance to the exhibition room. In fact, this video footage corresponds with another video shown in the second-floor lounge: partial footage from the 1973 ABC Television production of the series Atorie wo Tazunete (Visiting Studios). Comparing the two, it is amazing to find that the fundamental work of bashofu production has been passed down to this day. On the other hand, the passage of time is evident in changes to details such as the environment or outfit of the workers, while also intriguingly indicating that the free and lively spirit of the Kijoka women in 1973 has transformed into a tranquil moment that dominates the screen in the 2014 documentary footage. What overflows from the intentions behind these two pieces of footage and touches us is what brings us the undeniable sense of weight that the term “important intangible cultural property” conveys.

In recent years, exhibitions related to bashofu have been held in various locations nationwide. Among the major ones were “Bashofu: Living National Treasure Toshiko Taira and Kijoka Artisanship” at the Okura Museum of Art (2022); “The Story of Kijoka Basho-fu” at the Japan Folk Crafts Museum, Osaka (2023); “Bashofu: Living National Treasure Toshiko Taira and Kijoka Artisanship, “Eki” KYOTO (2023) and the “Bashofu Exhibition” at the Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum (2024). The placement of this exhibition within this series of events is something worth contemplating.

Photo by Ishikawa Koji

Visitors to this exhibition may be perplexed by the similarities in appearance between the works of the Important Intangible Cultural Property Holder Taira Toshiko and of the Kijoka Bashofu Weaving Studio. Moreover, they may proceed without receiving an explanation of the relationship between the Kijoka Bashofu Weaving Studio and the Kijoka Bashofu Preservation Society (hereafter referred to as “the Preservation Society”). While the former two can easily be imagined as the leading figure at her studio, the relationship between the latter two is rather complicated.

The key to understanding this lies in the captions. Upon checking the information on each work, it becomes evident that the Tokyo National Museum and the ACA own most of the Preservation Society’s pieces. Since the works owned by the Tokyo National Museum were transferred from the ACA, the Preservation Society’s pieces are essentially considered as the ACA-related.

This is because the Preservation Society is a holding group of Important Intangible Cultural Property. According to the Society’s regulations, its main purpose is to preserve the traditional technique of bashofu, while focusing on the training of successors as the principal axis of its project. Therefore, the Preservation Society is not geared toward the daily production of works, meaning works under its name are produced either as part of the Important Intangible Cultural Property successor training project or pieces purchased by the ACA as a part of the technique recording project.

Nevertheless, it is possible that such an explanation was intentionally avoided. In the exhibition room, materials related not only to the Preservation Society, but also to bashofu itself, such as maps and timetables, are omitted, and explanations are kept to a minimum. It is as if the viewers are expected to engage with the works independently and sincerely. This is a significant contrast to the other bashofu-themed exhibitions mentioned above.

In a sense, it challenges the viewer’s observational abilities. For instance, three bundles of fibers, made using the “u-biki” process (ito-basho fiber extraction), were hung near a banner containing an article in the Room of “Emerging Ideas” on the second floor. There was no disclosure of its meaning in the exhibition room. However, a careful comparison of the colors, luster, and other qualities of each bundle reveals significant differences in the quality as raw materials.

Photo by Ishikawa Koji

A similar challenge can also be observed in the display cases where the works of Taira Toshiko (#46) and of Kijoka Bashofu Weaving Studio (#66) are exhibited side by side. Both pieces utilize the “Teyui-gasuri (hand-tied Kasuri textile)” technique to create traditional Okinawan patterns, but upon close observation, distinct differences in their expressions become apparent. Combining subtle techniques, such as slightly shifting the Kasuri thread and changing how it is woven into the ground thread, Taira successfully charged her Kasuri bird with a sense of speed powerful enough to soar into the sky. Once viewers are aware of these differences, they cannot help but be sensitive to the differences between other works, and their view toward the entire exhibition will start to change. The time spent to reach this realization suggests that it is not something that is given, but rather expected to be acquired through effort on the part of each viewer. Within this process lies the true joy of viewing these works, and ultimately, the essence of visiting the exhibition. Moreover, this moment of realization also elucidates the solid intention of the exhibition organizer, who thoroughly insisted on presenting those artworks as an art museum.

Photo by Ishikawa Koji

This exhibition offered an opportunity to reacknowledge that exhibitions are an experience. After reviewing the show, I had the chance to sit alone on the elegant sofa designed by Kuroda Tatsuaki in the lounge and enjoy its comforting texture. Outside the window, the landscape of Kanazawa swayed in the summer sunshine, accompanied by the voice of Taira Toshiko from her younger days. It truly was a moment of supreme happiness.

*This contribution is a review of the Session A (July 11th to 27th) of the exhibition schedule. The exhibition period consisted of five sessions, from A to E, and included a total of three exhibition replacements.

(Gendai no me, Newsletter of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo No.640)

Release date :