Watch, Read, Listen

Newsletter of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Exhibition Review Techniques Cultivated by Weather, Weather Reflected in Art

Back

Ever-changing dependent on the time and place, weather is an integral part of our lives. At the same time, each region’s particular climate—shaped by the entirety of daily weather conditions—produces four distinct seasons and cultivates nature. It weaves local culture and enriches the activities, arts, and customs of the people who live there. This of course includes crafts.

This exhibition is an attempt at rethinking the relationship between Ishikawa Prefecture and crafts from a new perspective, that of “weather.” It is a fitting theme, as the exhibition is in commemoration of the fifth anniversary of the National Crafts Museum’s relocation to Ishikawa Prefecture and dedicated to the recovery from the 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake.

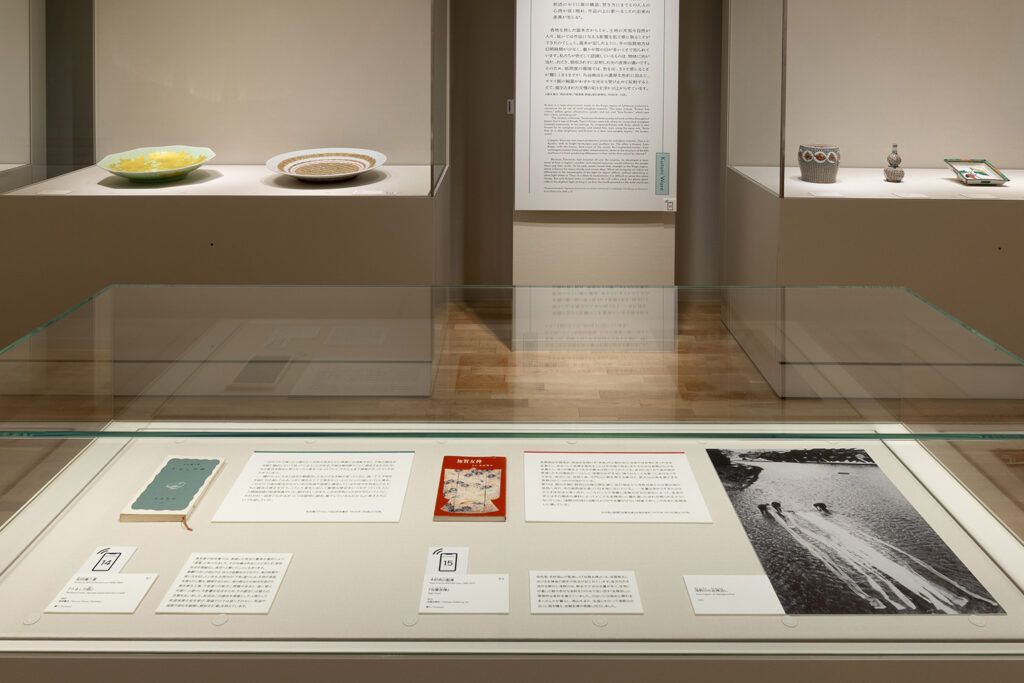

The exhibition comprises two sections that explore the relationship between “technique and weather” and “artistic expression and weather” in crafts. It exhibits works from the 1920s to the present by artists who have a connection to Ishikawa Prefecture.

Section 1: Living with weather, creating with weather features works of lacquer, ceramics, dyeing, weaving, and metal craft, and demonstrates the deep connection Ishikawa Prefecture’s lacquerware, gold leaf, Kutani ware, and Kaga yuzen silk dyeing have to local weather, mainly in terms of technique. It is an attempt to focus on works from the perspective of production techniques people rarely have the opportunity to see via the familiar phenomenon of weather.

The fact that weather influences the techniques used to produce crafts may be a surprise to many visitors. The key to this can be found in two books, The book of urushi: Japanese lacquerware from a master (work number R-1), written by Matsuda Gonroku, and Kaga Yuzen (work number R-2), edited under the supervision of Kimura Uzan [Fig. 1]. The words of these artists, who worked both with and against the weather in creating their art, lends credibility to the idea that the creation process of the exhibited works is deeply connected to weather. Standing in front of Ornamental box, heron design, maki-e by Matsuda Gonroku (work number 5) with this in mind, one can imagine how Matsuda prepared the lacquer in each step—the undercoat, second coat, top coat, and maki-e decorations—and used it to create the work while feeling the temperature and humidity of the weather with his body, just as we experience the heat, cold, dryness, and humidity of the weather in our daily lives, sometimes giving us joy and other times challenges. When you realize that the artists create their works day to day while making adjustments based on the weather in the same way that we adapt our lifestyles to the weather, you will be able to identify more with the works behind the glass and the techniques used to produced them.

Photo by Ishikawa Koji

Section 2: Gazing at the sky, awaiting spring features works inspired by the weather of Hokuriku and other areas. There are many traditional tea utensil masterpieces that have names relating to weather, but seeing the works made with various materials in this section made me realize how compatible the motif of weather is to artistic expression in crafts. Weather phenomena rarely have a fixed visual form. We remember the phenomena as a combination of non-visual sensations like temperature, humidity, smell, and the feeling of wind and rain. Crafts excel at both concretely depicting formless phenomena with decorations and abstractly expressing them through patterns and the shape of the work. And because crafts have such a strong connection to the materials they are made from, they allow the viewer to imagine the material’s texture and temperature. Weather and artistic expression both appeal to multiple sensations, and seeing craftwork portraying weather made me realize that they accentuate each other’s essential elements.

For example, Kanshitsu box, “Fresh Snow” by Mizuguchi Saki (work number 46) is a vivid vermilion. The color is quite different from white snow, but it somehow seems to fit the theme of snow. Walking around the case, you will notice that the exquisite irregular shape made from kanshitsu (a technique of sculpting by layering cloth with lacquer) brings to mind a plump shape made of piled snow in the blowing wind. And the nuritate (a technique of applying lacquer as the final coat and letting it harden without polishing it) vermilion lacquer creates a gentle texture that accentuates the shape, invoking the image of the moist and fluffy snow after it has stopped snowing [Fig. 2]. If you look at the works in Section 2 with a focus on how they express weather, you will find that the key is in techniques like the kanshitsu and nuritate of Mizuguchi’s work. Thinking back to Section 1, you will realize that these techniques were cultivated by weather. I only have space to mention a few works here, but the exhibition features many. I hope you thoroughly enjoy the installations from the perspectives of the rich artistic expressions of each work and the techniques that made them possible, and of the weather of Hokuriku.

Photo by Ishikawa Koji

The majority of the exhibited works in Section 1 and 2 are Japanese lacquer art. Japanese lacquer is made from the sap of the lacquer tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum). After extracted, the sap hardens due to a chemical reaction that proceeds under specific temperature and humidity. Therefore, lacquer art techniques are closely related to climate, and the way they are made differs by region. For example, if you take lacquer of the same composition and use it for the same purpose at the same time of year in Ishikawa as in Tokyo, it will not go well. Although we lump “lacquer art techniques” under one blanket term, each one that has been passed down for many years in their respective region are tailored to the local climate and have evolved using the materials and tools produced by the local environment. This isn’t something unique to lacquer art.

Thinking back on the exhibited artists, it is surprising how many of them are connected through mentor or instructor and student relationships. Through the exhibited works, the exhibition shows how the craft techniques that are rooted in Ishikawa have developed in the region’s distinctive climate, how those techniques have been passed down from person to person, and how the artistic expressions that are inspired by the landscape have flourished across generations [Fig. 3].

Photo by Ishikawa Koji

(Gendai no me, Newsletter of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo No.640)

Release date :