Exhibitions

2017-1 MOMAT Collection

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

The collection exhibition from May 27 – November 5 , 2017

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection! Let us start by introducing a few of the notable pieces in this edition of the exhibition. First, in the “Highlights” display (Room 1, 4th floor), you will be greeted by works that are perfect for the summer season, such as Kaburaki Kiyokata’s Boating Excursion on the Sumida River (May 27-July 17) and Kawabata Ryushi’s Flaming Grass (July 19-Sept. 10).

In Room 5 (4th floor), we feature Western modern art from the museum’s holdings. In terms of understanding the Western influence on Japan, these works are an indispensable part of the collection. And speaking of the relationship between the West and Japan, we also take a special look at Fujita Tsuguharu, who was active in Paris, in Room 6 (3rd floor), and at Kuniyoshi Yasuo, who worked in the U.S., in Room 7. We hope that you will enjoy retracing the footsteps of these artists who searched for their own identity in two different cultural spheres.

From Sept. 12. to Nov. 5 , we present a small exhibit to Higashiyama Kaii in Room 8 and 10 (3rd floor). Though the museum contains a large number of works by Higashiyama, due to the artist’s popularity, they are often on loan to other museums. This is a rare opportunity to see them all at once.

Finally, in Room 11 and 12 (2nd floor), we shed light on art movements of the ’60s and ’70s by focusing primarily on recent acquisitions.

We hope that you will enjoy this edition of the MOMAT Collection, filled as it is with many and varied works.

translated by Christopher Stephens

Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 14 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as Important Cultural Properties. These include nine Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, four oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Nakamura Tsune, Portrait of Vasilii Yaroshenko , 1920

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut Through a Hill , 1915

- Harada Naojiro , Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Tsuchida Bakusen, Serving Girl in a Spa, 1918 (Exhibit Date: May 27 – July 17, 2017)

- Hishida Shunso, Wong Zhaojun [the Chinese princess], 1902, Long term loan (Zenpoji Temple Collection) (Exhibit Date: September 12 – November 5, 2017)

- Please visit the Important Cultural Property section Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation A Room With a View is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F (Fourth floor)

Room 1 Highlights * This section presents a consolidation of splendid works from the collection, with a focus on Master Pieces.

Room 2– 5 1900s-1940s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

A Room With A View

Reference Corner

Room 1 Highlights

Over 200 works are lined up in this 3,000-square-meter space – these extravagant conditions are the distinguishing feature of the MOMAT Collection. In recent years, however, we have received an increasing number of comments like, “They’re so many things to see, I’m not sure what to look at!” and “All I want to do is have a quick look at the important works in a short period of time!” This prompted us to create the “Highlights” corner to allow you to savor the essence of the collection, with a focus on Important Cultural Properties.

In this edition, we will change the Nihonga works on display twice during the exhibition period to present a total of seven works. Of special note are Kaburaki Kiyokata’s Boating Excursion on the Sumida River (on view until July 17), a depiction of modern boating, Kawabata Ryushi’s Flaming Grass (on view from July 19 to Sept. 10), which portrays summer grass in gold paint on a dark blue ground, and Hishida Shunso’s Wong Zhaojun (The Chinese Princess) (on view from Sept. 12), an Important Cultural Property from Zenpo-ji Temple (Tsuruoka, Yamagata Prefecture) that is currently deposited in the museum. In addition to Important Cultural Properties by Harada Naojiro and Kishida Ryusei, both mainstays in the field of oil painting in the Highlights section, we also feature two recent additions to the museum collection: Matsumoto Shunsuke’s Black Flowers and Yamashita Kikuji’s The Tale of Akebono Village.

Room 2 Meiji Painting: Realistic Depictions of Nature

One of the top priorities for Meiji Period artists, who struggled to modernize painting, was to depict nature in the most realistic manner. This was not only the case in landscape painting, but also extended to what was broadly termed “genre painting.”

The first step was to come up with a special kind of framing. By detaching part of a forest with a bird’s-eye view, Kuroda Seiki’s Dead Leaves gives us the sense that we are actually roaming through it. By using framing that intentionally provides us with a fragmented view instead of describing the entire scene, the work sets out to reproduce a vivid experience.

The second step was to establish a link between people’s lives and nature. The farmers cutting wheat in Minami Kunzo’s One Day in June, and the brawny sailors in Wada Sanzo’s South Wind are depicted as part of the natural landscape. This was apparently rooted in the notion that nature was something meant to be approached and conquered. Both works show men with bare chests in the center of the pictures, suggesting that the human body and physical labor were viewed with the same aesthetic terms as this applied to nature. This perspective was perhaps indicative of city dwellers.

Room 3 Love and Cream Buns

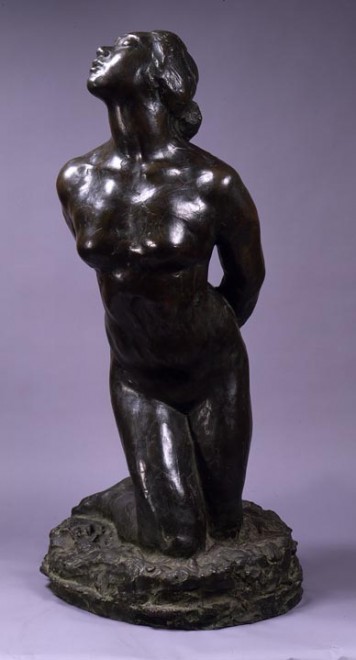

Established in 1901, the bakery Shinjuku Nakamuraya is still headquartered in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo. Its founders, Soma Aizo and his wife Kokko, loved the arts and many young artists gathered at the bakery. These included sculptors such as Ogiwara Morie, Nakahara Teijiro, and Tobari Kogan, and painters such as Nakamura Tsune and Yanagi Keisuke. Perfectly conveying the freedom of the period, associated with so-called “Taisho democracy,” Nakamuraya was one of the era’s most important art salons.

The art salon concept originated in Europe, and its most significant feature was an attractive proprietress who discovered talented people. At Nakamuraya, Soma Kokko fulfilled this role. Ogiwara Morie was in love with Kokko and his work Woman is said to be based on her appearance. For his part, Nakamura Tsune fell first for Kokko and then later for the Somas’ oldest daughter, Toshiko. In both cases, however, his love went unrequited. As these examples suggest, in art salons during the Taisho democracy era, love was an important source of nourishment for art. So what about cream buns? In 1904, Nakamuraya became the first shop in Japan to make the baked delicacy.

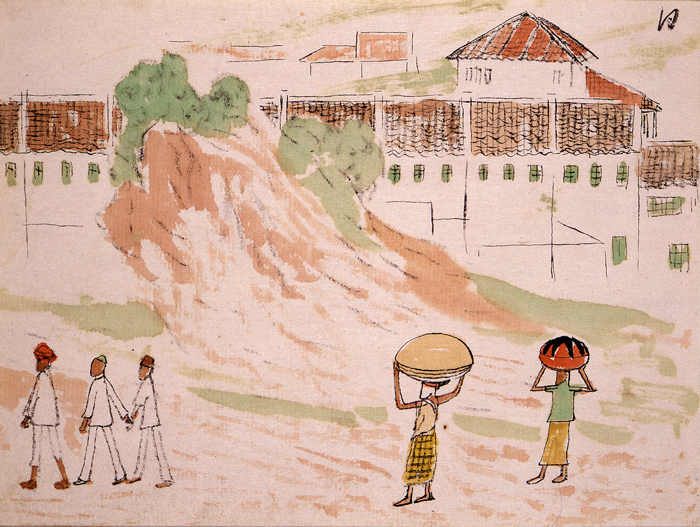

Room 4 Artists’ sketched records of travels to India and Asia

In this room we present sketches by Japanese-style painters Imamura Shiko (1880-1916) and Kawabata Ryushi (1886-1966) made while traveling abroad, with the featured works changed twice so the show has three sessions.

Imamura boarded a cargo ship to India in 1914. The ship stopped in China, Singapore and elsewhere before berthing in Kolkata for 15 days. Imamura is thought to have obtained information in advance about China, and depicted well-known sights. Meanwhile, from his sketches of India and Southeast Asia, it is evident that the foreign visitor took an interest in the everyday lives of people in other countries.

Kawabata traveled to the South Seas and China to make a series of drawings to be shown at the Seiryusha exhibition. At the time, territories such as Saipan and Palau were controlled by Japan. Also, as it was during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the artist was embedded with the former Japanese Army and Navy.

These sketches show an admiration and passion for other countries. They are visually appealing and serve as historical materials convey the conditions of the time. On the other hand, it should not be forgotten that the creation of these sketches was inseparable from some element of oppression of foreign peoples.

Room 5 Is There an Absolute West?

We are pleased to present a selection of works by non-Japanese artists produced between the 1890s and 1960s. At MOMAT, we have been long sought to position Japanese art (especially Western-style painting) in terms of its distance from the West, going back to the exhibition Development of Modern Western-Style (Oil) Painting: Europe and Japan, which was held in 1953 shortly after the museum opened. This process is similar to that of Japanese artists in the early 20th century, who looked at black-and-white reproductions of Western art in magazines and traveled overseas to see them in person, thereby establishing their own relative positions. At the time the West was seen as an absolute pole, a North Star by which to navigate. For this reason, the “non-Japanese artists” featured here are almost entirely Western in origin.

It was not until the mid-1970s that the museum was able to purchase oil paintings by non-Japanese artists. Since then, we have been collecting works by these artists, from the standpoint of their influence on modern Japanese art.

Today, the paradigm of “the West / Japan” has become more relativistic, and much work by artists who are neither Japanese nor Western has been added to the collection, but “the West” continues to be a crucial point of reference. As you view this section, take a moment to imagine what kind of inspiration Japanese artists may once have derived from these works.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building

Room 6 Fujita, Foujita a.k.a. Léonard

Fujita Tsuguharu was born in 1886 to the army doctor Fujita Tsuguakira and his wife Masa. In 1913, at the age of 26, Foujita moved to France after studying oil painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. In Paris, Foujita developed friendships with Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani, and searched for his own means of expressing himself. In the 1920s, Foujita became the darling of the École de Paris for his paintings of women, which were described as “le grand fond blanc” (milky white ground). With his bobbed hair and round glasses, Foujita, or FouFou (French for “frivolous person”), as he came to be known, even became a topic of conversation in fashionable circles.

After traveling around Central and South America from 1931 to 1933, Fujita returned to Japan. In the late ’30s, he became involved in making paintings that documented the war, but after the war ended, he came under fire for cooperating with the military government. In 1949, Foujita returned to Paris by way of the United States, and in 1955, he became a French citizen. In 1959, he was baptized Catholic and assumed the name Léonard Foujita. The artist died in Zürich in 1969. We hope you will enjoy looking at Fujita, Foujita or Léonard’s works, a reflection of his multifaceted way of life, which was both national and international.

Room 7 Kuniyoshi Yasuo: Somebody Tore Something of Mine

Where on earth are these women going as they head into this desolate area? Who is the woman standing in front of the ripped posters staring at?

In 1906, Kuniyoshi Yasuo (1889–1953) moved by himself to the U.S. at the age of 17. He continued to work there most of his life, only rarely returning to Japan. Kuniyoshi lived through a turbulent period in which his motherland and his adopted homeland fought each other, and in his later years he was recognized as a prominent painter in the U.S.

In 2004, 50 years after a posthumous exhibition of Kuniyoshi’s work (held in 1954, the year after his death), MOMAT presented a retrospective of the artist’s career. In this exhibit, centering on a group of works that are deposited the museum (which also led to the retrospective), we focus on Kuniyoshi’s post-World War II work.

Depicting women and children, Kuniyoshi’s motifs are by no means unfamiliar. It is difficult, however, to decipher exactly what these figures are doing in a given situation and what these seeming absent-minded people might be thinking. Suggesting that the complex thoughts of those at the mercy of history should not simply be revealed to others, the truth in these works seems to be hidden behind multiple layers of a mysterious curtain.

Room 8 The Shadow of America

Postwar Japanese society was permeated by America. This was constantly reflected by a host of contradictory emotions, such as the aversion to the continued U.S. military presence following the signing of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and at the same time a fondness for American culture such as art, movies, music, and fashion. This complex relationship can also be seen as central to the creation of postwar Japanese war images.

Depicting a U.S. base in a critical manner as a foreign presence that threatens everyday life, Nakamura Hiroshi’s The Base reflects the sense of elation that surrounded anti-military protests in the 1950s. But with the period of rapid economic growth that began in the 1960s, military bases were no longer a popular subject. While on the one hand memories of the war were receding, a series of war stories in boys’ comics amazingly attracted dedicated readers, and plastic models of tanks and fighter planes made by the Tamiya corporation suddenly began to enjoy great popularity. During the Vietnam War, works such as Kojima Nobuaki’s Boxer, influenced by the downfall of the American hero, and Sphinx, Okamoto Shinjiro’s parody of American-style illustrations, provided a cool view of the “inner America.”

Room 9 Suda Issei, Fushi kaden

Fushi kaden is a series that was irregularly serialized in eight parts in Camera Mainichi magazine between December 1975 and December 1977. In 1978, it was compiled in a photo book. It is known as the work that established Suda Issei’s reputation, including his receiving the Photographic Society of Japan Nippon Photography Association Award Newcomer Award in 1976 while the series was in progress.

The scenes of traditional festivals that appear prominently throughout the works were shot in various parts of Japan, including the Kanto, Hokuriku, and Tohoku regions. In other words, this is also a photographic record of Suda’s journey. Both journeys and festivals lie outside the usual bounds of time and space. Does this mean the world depicted in Fushi kaden is an extraordinary realm of space-time? In fact, the photographer stated that from his earliest years, his subject was consistently “the ordinary.” He wrote in the photo book Ningen no kioku (Human Memories), “The most humdrum scenes of everyday life are, for me, brimming over with tensions.” Whether traveling or at home in his own neighborhood, he sought out and responded to the same kinds of scenes and captured them on film.

The title is drawn from Fushi kaden (which has a range of translations including “Transmission of the Flower of Performance”), an early 15th-century treatise on Noh theater by the actor and theorist Zeami.

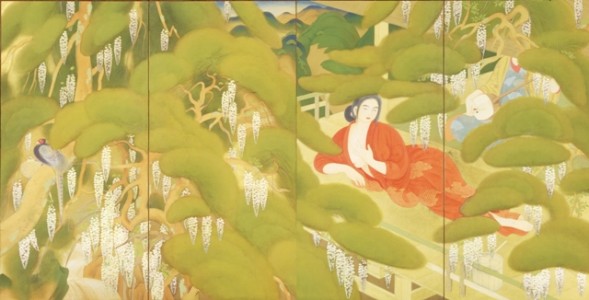

Room 10 Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai: Before and After

Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) in Kyoto is said to have undergone a significant change as a result of Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai (the Society for the Creation of National Painting), established in 1918. Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai was an art group organized by five students in the first class at Kyoto-shiritsu Kaiga Senmon Gakko (Kyoto City Vocational School of Painting) ― Tsuchida Bakusen, Ono Chikkyo, Nonagase Banka, Murakami Kagaku, Sakakibara Shiho ― who were joined by Irie Hako the following year and held a total of seven exhibitions through 1928.

In establishing the society, they declared that they would place the greatest emphasis on respect for freedom of creation. This marked the arrival of Taisho Democracy in the ancient capital, where the world of Nihon-ga painting was still dominated by long-held traditions. Moreover, after Tsuchida and the other members presented major works that reflected their own unique personalities at the first Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai exhibition, it grew into a public open-call exhibition attracting young artists not only from Kyoto but from all over the country.

The flip side of the pursuit of individuality is surely departure from tradition. The increasingly influential activities of Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai spelled the end of the Shijo School, which originated centuries earlier in Kyoto and held sway until the Meiji Period (1868-1912).

This room showcases works by Kyoto Nihon-ga painters involved in Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai, as well as by artists of the preceding and ensuing generations.

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Gallery 4

* A space of about 250 square meters. This gallery offers cutting-edge thematic exhibitions from the Museum Collection, and special exhibitions featuring photographs or design.

Producing / Discussing / Looking at / Hearing, Sculptures

Primarily from the Museum Collection

Room 11, 12 Art of the 1960s and 1970s: New Additions to the Collection

Around 1970, artists revisited a practical approach to the question, “What is art?” Reconsidering basic modes of production and presentation, and criticizing the art museum as representing the authority of the establishment, they explored both rejection and expansion of the very concept of art. A key feature of this era is the idea or concept comprising a major part of the work. This tendency, which took various forms such as the recording of time (Kawaguchi Tatsuo, Kawara On, Nakahira Takuma), the exploration of exteriors (Akasegawa Gempei, Robert Smithson) and the use of new media (Idemitsu Mako), resulted in both works made with plain everyday materials and those that were entirely non-materiall, vexing people who had come to museums in search of “beauty.”

If works that deconstruct art and criticize the museum as a system become part of a museum’s collection, does that deprive the works of their innate power and relegate them to the dustbin of history? Or does exhibiting these pieces present a valuable opportunity to re-examine and revitalize the museum’s entire collection? In this way, we hope that these works from the 1960s and 1970s will prompt people to “re-deconstruct” art in the 2010s.

About the Exhibition

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

May 27 – November 5 , 2017

- Time

-

10:00-17:00 (10:00 – 20:00 on Fridays and Saturdays)

MOMAT Collection and Gallery 4 open until 21:00 on Fridays and Saturdays during The Japanese House : Architecture and Life after 1945 (July 19-October 29)

*Last admission is 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

※Closed on Mondays (except July 17, September 18, October 9) and July 18, September 19, October 10

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)*Including the admission fee for Producing / Discussing / Looking at / Hearing, Sculptures.

*The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more.

*All prices include tax.

*Free for high school students, under 18, seniors( 65 and over ), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

* Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission ( a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free ).

*Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

*Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

*Free for students after 5:00 PM on Fridays and Saturdays between Friday, July 21 and Saturday, August 26, 2017. - Discounts

-

*Evening Discount (From 5:00 pm on Fridays and Saturdays) Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Free Admission Days

-

Collection Gallery and Gallery 4

Free on June 4, July 2, August 6, September 3, October 1, November 3, November 5, 2017 - Organized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo