Exhibitions

MOMAT Collection (2023.5.23–9.10)

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

Highlights

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection!

To briefly introduce some features of the museum’s exhibitions of works from the collection: First, its scale is one of the largest in Japan, displaying approximately 200 works each term from the museum’s holdings of over 13,000 works acquired since its opening in 1952. Also, it is one of the foremost exhibitions in Japan, tracing the arc of Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day through a series of 12 rooms, each with its own specific theme.

This term, we are pleased to offer another abundant lineup of works. To focus on just two of the highlights: first, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Rooms 2 through 4 on the 4th floor survey relationships between the earthquake and art, highlighting topics such as the devastation of the affected area, reconstruction, and social fragmentation.

Also, Rooms 7 through 9 on the 3rd floor feature the work of photographer Ohtsuji Kiyoji, who would have turned 100 this year were he still alive. Ohtsuji’s avant-garde photographs earned acclaim in the immediate postwar years, and here we also showcase his importance as a writer and educator along with works of art closely associated with him.

National Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 18 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as National Important Cultural Properties. These include twelve Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following National Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection) | Room1

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915 | Room1

- Nakamura Tsune, Portrait of Vasilii Eroshenko, 1920 | Room1

Please visit Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F(Fourth floor)

Room 1– 5 1880s-1940s

From the Middle of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room 1 Dawn of the Modern Era

As the Meiji Era (1868-1912) began and construction of a new modern state progressed, Japanese people came into contact with Western art, which was making inroads in Japan at a furious pace. Having been stirred to action by the great wave of art from the West, in the 20th century personal expression by countless individuals began to emerge as if surging up from below, and the shape of “modernity” gradually came into view. One thing that can surely be said of the modern era is that it was the age of the individual.

While such individual artists were too numerous to count, the Bunten exhibition (sponsored by the Ministry of Education) was established in 1907 in an effort to bring this surge under control and establish state-sanctioned forms of art. The MOMAT collection traces its origins back to 1907, the year of the Bunten’s inception. In this room, we have selected masterworks from the museum’s collection that convey various aspects of the early 20th century prior to the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923). Some artists sought to connect Western art to pre-modern traditional art, others sought to place Western techniques at the core of their practice, still others to carve out entirely original modes… Witness the tumultuous advent of the modern era in Japan.

Room 2 100th Anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake: Art of 1923

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake, which struck the Kanto region at 11:58 AM on September 1, 1923, with its epicenter offshore in Sagami Bay and a magnitude of 7.9. A heavy rain that had been falling the night before had abated, and on a fiercely windy autumn Saturday, the Takenodai Exhibition Hall in Ueno Park was bustling with people as the 10th revived Inten Exhibition and the Nika Exhibition both opened their doors to the public. Just as artists were gathering, there was a violent jolt and the exhibitions were immediately halted.

While the exhibition hall survived the collapse, at both venues sculptures fell from their pedestals, breaking and lying strewn about, while paintings tilted and frames were twisted. One visitor to the Nika Exhibition recalled, “The scene was like looking at a Cubist painting spinning around in circles.” Works that had survived unharmed were gathered, and both exhibitions reopened in October in Osaka, with the revived Inten subsequently traveling to Hosei University and the Nika Exhibition to Kyoto and Fukuoka. Here we present works from the museum’s collection that appeared in the exhibitions at the time.

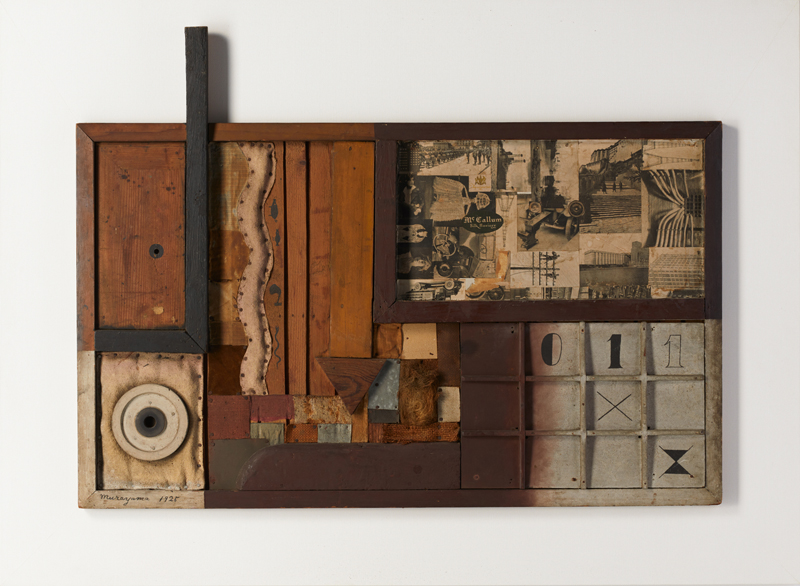

Room 3 100th Anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake: Devastation and Recovery

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 caused massive and widespread damage, affecting nearly two million people, leaving 100,000 dead or missing, 100,000 houses completely destroyed, and 210,000 houses burned to the ground. In an era before TV or the internet, artists took up brushes and cameras to document the devastation. Eventually they resumed exhibition of their works and became involved in the recovery effort in various ways, such as proposing designs for barracks that housed evacuees, making proposals for urban redevelopment, and depicting the reconstruction process. The art critic Takumi Hideo later wrote of the impact of the Great Kanto Earthquake on art: “Similarly to the way in which Dada arose out of the rubble of World War I, the devastation caused by the Great Kanto Earthquake provided fertile soil for the emergence of Dada-like tendencies. The avant-garde flourished rapidly during the period of psychological turmoil that followed the earthquake” (Kindai Nippon Yoga no Tenkai [Development of Western-Style Painting in Modern Japan], Shoshinsha, 1964). Avant-garde art, which had been emerging even before the earthquake, was accelerated in the aftermath of the disaster.

Room 4 100th Anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake: Social Distortion

While postwar recovery led to the development of modern urban culture, strains in the fabric of society gradually became evident as well. Violence on the part of the authorities and vigilante groups in the wake of the earthquake gave rise to anti-establishment discourse, and artists who were inclined toward anarchism and socialism eventually adhered to Proletarian Art. Many of these artists were part of emerging Taisho Era (1912-1926) art movements such as Mirai-ha Bijutsu Kyokai (the Futurist Art Association), Action, MAVO, Daiichi Sakka Domei (DSD, the Primary Artists’ Alliance), and subsequently Sanka, which united these groups. In 1929 the Japan Proletarian Artists’ League was formed, and from 1928 to 1932 the Proletarian Art Exhibition was held, presenting many works that depicted workers’ demonstrations and strikes and the factories where they toiled. The artists’ works spanned a wide range of genres, including not only paintings and sculptures but also prints, posters, plays, manga, and publications. However, after a crackdown including amendment of the Maintenance of Public Order Act and police repression, the Proletarian Art movement had subsided by 1934.

Room 5 Forms That Look Like Something

In conjunction with the exhibition of Antoni Gaudí, known for his visionary architecture inspired by natural forms, this room features works that are abstract and contain biomorphic imagery that evokes plants, animals, and human forms. The term “biomorphic,” meaning “resembling the forms of living organisms,” came to be used in the art world in the 1930s to describe a trend toward the non-geometric in abstract art. This term was particularly applied to forms in the Surrealist painting and sculpture of Joan Miró, Jean (Hans) Arp, Alexander Calder, and others. A similar tendency appears in the works of Japanese Surrealists such as Okamoto Taro and Terada Masaaki. These works feature a wealth of forms that oscillate between the inorganic and the organic, as if in a constant state of flux. They represent endeavors to have the abstract and the figurative coexist in a work of art, or the search for images that are unconstrained by such frameworks altogether.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 Painting, 1920s-1940s: Focus on the Figurative

In Japan, the years from around 1920 through the 1940s were rife with destruction and chaos caused by wars and natural disasters. In the midst of this tumult, there were artists who sought to return to their own personal perspectives, and to explore the fundamental question of what they ought to express.

This tendency coincided with a broad social shift toward reverence for tradition and reversion to Japanese values, and was part of a campaign to cultivate quintessentially Japanese painting that did not merely imitate Western works. For example, Umehara Ryuzaburo embraced traditional painting materials such as iwa-enogu (mineral pigments) for the unique colors they produced, while in Sakamoto Hanjiro’s use of pale hues and subtle control of tones to depict a horse quietly emerging from the background, we see an East Asian view of nature that integrates the subject and the surrounding environment.

Meanwhile, Matsumoto Shunsuke’s tranquil world of transparent color fields and black line drawing seems to reflect a solitary inner life, and Ai-Mitsu’s Self-Portrait, which depicts the artist standing with dignity and gazing into the distance against a dark background, represents his determined struggle not to lose himself even amid the bleak and despairing wartime years.

Room 7 Experiments and Collaborations 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Ohtsuji Kiyoji (1)

Ohtsuji Kiyoji was a photographer who gained attention for avant-garde works shortly after World War II, and later was influential as a writer and educator in the photography field. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth, this exhibition of works from the museum’s collection dedicates three rooms to tracing some of the arc of Ohtsuji’s career, which is closely tied to the development of postwar art in Japan.

The first room, entitled “Experiments and Collaborations,” showcases two creative groups in which Ohtsuji participated in the 1950s: Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop) and Gurafikku Shudan (Graphic Group). Jikken Kobo was formed in 1951 by a group of young artists, musicians, and other creators in the circle of the poet and critic Shuzo Takiguchi, and was known for unconventional, interdisciplinary activities including collaborative stage productions. Ohtsuji participated in Jikken Kobo beginning in 1953, and photographed the members and their activities in diverse situations.

The same year, Ohtsuji also took part in formation of Graphic Group, a group of graphic designers, painters, and photographers who collectively organized and produced exhibitions and publications. They also worked in a spirit of experimentation and collaboration that included innovative advertising proposals and unique films.

Room 8 Gutai and Matter 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Ohtsuji Kiyoji (2)

Ohtsuji Kiyoji engaged in many photography projects involving fine art, including his work for the art magazine Geijutsu Shincho, from which he received commissions for several years beginning in 1956. In this room, we focus on artists and works documented by Ohtsuji.

The Gutai Art Association (usually known simply as “Gutai”), which sought “to present concrete proof that our spirit is free,” had a major impact on the art of its time. Ohtsuji’s photographs of the Kansai-based group’s 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition, held in Tokyo in 1956, capture this freedom of spirit, unconfined by conventional frameworks of art.

The 10th Tokyo Biennale: Between Man and Matter (1970) was a seminal exhibition that first showcased the artists who became known as Mono-ha (the “School of Things”) alongside their international contemporaries. Ohtsuji documented this exhibition from the installation of works onward.

Ohtsuji, whose work was initially inspired by the Surrealist concept of the object, was a photographer deeply concerned with the presence of things. The development of postwar art in Japan, which can be traced using Ohtsuji’s photographs as a through-line, shows a consistent lineage of exploration of “things” and “matter.”

Room 9 Uehara 2-chome 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Ohtsuji Kiyoji (3)

“What sorts of experiments do I want to conduct? I want to see whether or not there is a difference between the way I have always thought about photography, and the way I actually take photographs.”

This is a passage from the first installment of “Ohtsuji Kiyoji’s Laboratory,” a series of articles that Ohtsuji Kiyoji wrote for Asahi Camera magazine in 1975. Each installment consisted of his own photographs and text, and focused on what is or is not captured in a photograph, and what it conveys or does not convey to the viewer, using himself as an experimental subject. The series, which begins with thoughts about a photograph of objects on his work desk at home, ends with documentation of the demolition of his house in order to build a new one.

Aside from his commissioned works, Ohtsuji rarely established themes and went to specific places for the purpose of taking photographs, but he shot many works in and around his home in Uehara, where he resided for many years. In this room, the special exhibit on Ohtsuji concludes with a feature titled “Uehara 2-chome,” which highlights the gaze he cast on his immediate surroundings.

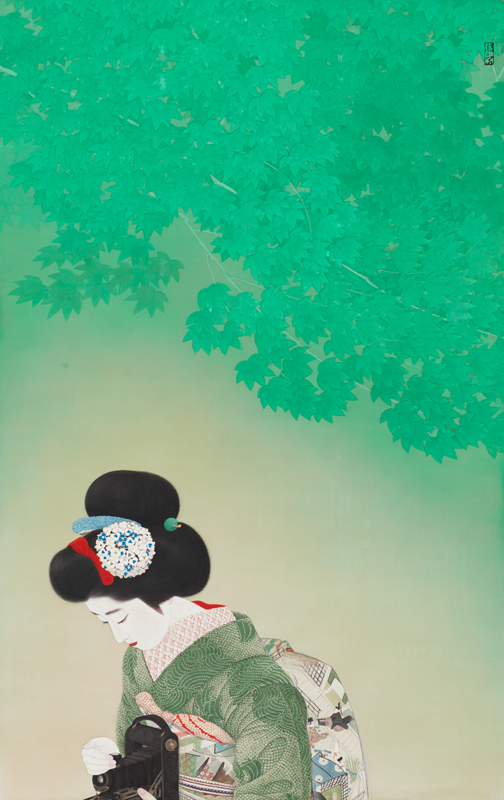

Room 10 New Acquisition and Special Exhibition: Ikeda Shoen, Way Back (1) (2023.5.23-7.17)

Ikeda Shoen (1886-1917) was born Sakakibara Yuriko, and was given the artist’s name Shoen by Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), under whom she studied, in honor of Uemura Shoen (1875-1949), also a female Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) artist. At the Bunten (Ministry of Education exhibition), the younger Shoen outshone Kaburaki Kiyokata (1878-1972) and her future husband Ikeda Terukata (1883-1921), both of whom studied under the same teacher, to win third prize each year from the first to the fourth exhibitions in succession, becoming a rising star. The romanticism of her works based on stories, and the dreamy expressions and fraught appearances of women in love, made her paintings extremely popular among women at the time.

Way Back, newly acquired by the museum in 2022, was exhibited at the 9th Bunten in 1915 in the so-called “Bijinga Room,” dedicated exclusively to bijinga (paintings of beautiful women). When first exhibited it was a six-panel folding screen, but today, with the loss of the two panels on the left, it has become a four-panel screen. Fortunately, however, the inimitable allure of Shoen’s charming female figures has not been lost. In conjunction with the unveiling of Way Back, here we are pleased to present a group of works by female artists, with a focus on Nihonga paintings and crafts.

Room 10 New Acquisition and Special Exhibition: Ikeda Shoen, Way Back (2) (2023.7.19-9.10)

Way Back, newly acquired by the museum in 2022, was exhibited at the 9th Bunten in 1915 in the so-called “Bijinga Room,” dedicated exclusively to bijinga (paintings of beautiful women). Here, as in the preceding term, we present Way Back and some other works by female artists, as well the work of painters who were closely associated with Shoen as painters of bijinga and genre paintings.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Gallery 4 Secrets of Restration

Room 11 Visual Labyrinths

The Passion facade of the Sagrada Família, designed by Antoni Gaudí, features a labyrinth carved in stone by the sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs. Labyrinths are known to have existed in most ancient cultures, and in the West, labyrinths at the entrances to medieval churches symbolized human movement through life toward the divine.

Labyrinths originally had a single path leading to the center, but the Renaissance saw the emergence of branching labyrinths that led people astray. Labyrinths, inside which we cannot locate the exit or where we are in relation to the whole, have fascinated people in all eras and cultures. Many labyrinths appear in works of art, including those of M.C. Escher. Here we bring together works that beckon the eye into labyrinths, from works depicting them to paintings with labyrinthine structures.

Room 12 Visual Labyrinths

Like the preceding room, this room contains labyrinthine paintings, sculptures, and video works that draw you further in the more you look at them. Here, whether a work is figurative or abstract is of no importance. Works depicting recognizable objects fascinate viewers by creating fictions in a way that only paintings can, for instance by rendering things in the most minute detail, or by placing objects in contrasting combinations.

Meanwhile, in abstract works, various elements including the concept, the creative process, and movements of the artist’s hand intertwine to stimulate our visual senses. This is true not only of paintings, but also of sculptures and videos. In addition to spatial elements such as form, color, and composition, the time a work took to create and the time spent viewing it may also be important factors in constructing an artistic labyrinth. We invite you to lose yourself in these labyrinths with no exits, and savor the artworks to the last detail.

Room13(Gallery 4) Before and After the Catastrophe

This term, on the 4th floor, the MOMAT Collection focuses on the Great Kanto Earthquake that struck 100 years ago this year. In this final room, we present works created before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. When placed side by side, the works seem to have commonalities in terms of bright, contemporary colors and a progression from personal, inward-looking expression to social concern, but how might they appear differently when grouped according to the theme of the earthquake?

The experience of a major disaster lingers in our memories as a dividing line between before and after. For example, when we see Kawaguchi Tatsuo’s Dark Box 2009, which encloses darkness, it may occur to us that the box contains air from before “that day,” or we may associate the faces painted by Kato Izumi with the devastated post-quake landscape. Of course not all of these works relate to the disaster, but we hope that this exhibit will offer opportunities to reflect not so much on how works themselves change over time, but on how changes in viewers’ perceptions can affect the way the works appear. In the small room are displayed two pairs of photographs by Miyoshi Kozo and Ushioda Tokuko, one of each pair taken before and after the earthquake respectively. We suggest that you view the works before having a look at the captions.

Hours & Admissions

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

May 23—September 10, 2023

- Time

-

10:00 a.m.—5:00 p.m. (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 p.m.)

*Last admission: 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

Mondays (except July 17) and July 18

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)- The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

- Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

- Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

- Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

- Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

- Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Organaized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo