Exhibitions

MOMAT Collection(2023.9.20–12.3)

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

Highlights

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection!

To introduce some features of the museum’s exhibitions of works from the collection: First, its scale is one of the largest in Japan, displaying approximately 200 works each term from the museum’s holdings of over 13,000 works acquired since its opening in 1952. Also, it is one of the foremost exhibitions in Japan, tracing the arc of Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day through a series of 12 rooms, each with its own specific theme.

Some highlights of the current term are as follows. Room 3 (“Taisho Touch”), Room 4 (“From Palm-of-the-Hand to Wall-Filling Scale”), and Room 10 (“A Carefree and Light-Hearted Ink Painter”) are all related to the special exhibition The Making of Munakata Shiko (opening October 6). These rooms can be enjoyed by both visitors who have already seen the Munakata exhibition and those who have not. In addition, we present a series of small exhibitions featuring individual artists, with Room 6 dedicated to the Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) painter Higashiyama Kaii, Room 7 to the printmaker Hiwasaki Takao, Room 9 to the photographer Gocho Shigeo, and Room 10 to the lacquer artist Taguchi Yoshikuni. Also, do not miss the special exhibit of abstract works by female artists in Gallery 4 on the 2nd floor.

We believe our curatorial team has successfully showcased the depth and breadth of the collection by making connections between thematic exhibits and presenting major works by important artists. Please enjoy your visit to the fullest!

National Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 18 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as National Important Cultural Properties. These include twelve Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following National Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection) | Room 1

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915 | Room 2

Please visit Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F(Fourth floor)

Room 1– 5 1880s-1940s

From the Middle of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room 1 Highlights

The MOMAT Collection exhibition of works from our permanent holdings features for than 200 items in a 3,000-square-meter space. It opens with the “Highlights” section, featuring highly prized works from the collection.

In the category of Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting), the popular works Flaming Grass (1930) by Kawabata Ryushi and Injured Yamatotakeru at the Spring (1928) by Yasuda Yoshihiko are displayed side by side. The latter, which had been entrusted to the museum for a long time, was officially acquired last year and will be unveiled as part of the collection for the first time in this exhibition.

In the area of sculpture we are pleased to present three pieces. In Yonehara Unkai’s masterpiece of Meiji-era carved wood sculpture Sugawara Michizane in His Boyhood (1907), the delicate rendering of the garment’s soft textures is a highlight. Enjoy comparing and contrasting it with another carved wood sculpture, Hirakushi Denchu’s polychromatic Homage to a Long Life (1944).

Outside the display cases we present some of the museum’s most treasured works, including Harada Naojiro’s Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon (1890), an Important Cultural Property. This time there is a particular focus on Western painting, with a splendid lineup including such recently acquired works as Pierre Bonnard’s Landscape in Provence (1932) and Paul Klee’s Thoughts in Yellow (1937).

Room 2 New or Old?

Determining the beginning of something is always a difficult task. The middle “m” in MOMAT stands for “modern.” But when did modern art really start? Half of these works were displayed in the Bunten, an annual exhibition launched by the Ministry of Education in 1907.

Though opinions vary, some have suggested that this event marks the beginning of modern art in Japan.

This was an era in which modern meant “avant-garde.” In other words, the recent past was seen as something old that should be rejected and surmounted. Though the Bunten was initially welcomed, it soon became a stronghold for rigid Academicism and a target of criticism among the younger generation. The rest of these works were made by artists who intentionally veered away from the exhibition.

Do these works, created some 100 years ago, convey the feeling that new things are more magnificent than old ones or vice versa?

Room 3 Taisho Touch

In conjunction with the exhibition The Making of Munakata Shiko, taking place in the special exhibition gallery, here we present Japanese art from the Taisho era (1912–1926), which was influenced by Western art of the same period.

It is well known that seeing a reproduction of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers as a frontispiece in the literary magazine Shirakaba was a pivotal moment that inspired Munakata Shiko to become an artist. In the early years of the 20th century the French Post-Impressionists, including Van Gogh as well as Gauguin, Cezanne, and Matisse, had a significant impact on the other side of the world in Japan.

In attempts to sum up the art of the Taisho era, phrases such as “expression of the inner self” are often used. Artists of the time encountered and engaged with new trends, leading to the widespread use of flamingly vibrant colors and highly dynamic brushwork. They were not so much imitating foreign art as absorbing from it ways of giving visual form to the passions within themselves. Take note of the touch that characterizes these works, which does not merely endeavor to reproduce the colors and forms of subjects, but asserts itself as an entity in its own right.

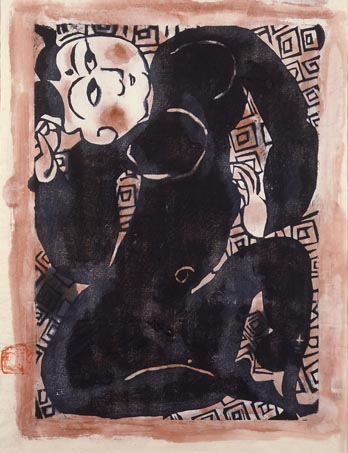

Room 4 From Palm-of-the-Hand to Wall-Filling Scale

Here we are pleased to present woodblock prints from the Taisho (1912–1926) and early Showa (1926–1989) eras, in conjunction with the special exhibition The Making of Munakata Shiko. In the 1920s, when Munakata Shiko first turned to printmaking, woodblock prints were predominantly small in scale, and were circulated in formats such as magazines and postcards and widely enjoyed as a tabletop art form. Groups of young printmakers brought their works together to create print magazines, building interpersonal networks with peers and art lovers. Meanwhile, this era saw the first inclusion of woodblock prints in competitive exhibitions. As printmaking joined painting and sculpture in the ranks of art forms for public exhibition, the sizes of works gradually increased in expectation of the spaces where they would be displayed.

Munakata’s powerful, large-scale prints and colorful personality entrenched his reputation as a one-of-a-kind artist. However, Munakata drew significant inspiration from contemporaries such as Yorozu Tetsugoro and Kawakami Sumio; Hiratsuka Un’ichi, who taught him printmaking techniques; and his acquaintance Onchi Koshiro, all of whom were exceptional printmakers of that era and gave Munakata invaluable support on his artistic journey.

Room 5 Aircraft, War and Art

In Japan, the first successful powered flight took place in 1910. Production of civilian aircraft began in the 1920s, and 1931 saw the opening of the first state-run civilian airport, Tokyo Airfield (which later became Haneda Airport).

The advent of airplanes introduced new vantage points and perceptions to 20th-century art.

Examples can be seen in the works of artists such as Murai Masanari, who referenced aerial photography in his paintings, and other artists took an interest in aeronautical engineering.

At the same time, airplanes were strongly associated with war and became an ideal subject for paintings depicting dramatic battle scenes. When works displayed at exhibitions held to raise funds for military aircraft are included, the range of works related to this theme becomes truly diverse. Kitadai Shozo’s Mobile Object was made using duralumin, a material originally used for aircraft and fighter planes in particular.

Please enjoy this overview of works, from a time spanning the war years, relating to airplanes, which can embody the human dream of flight or serve as weaponized machines far surpassing human power.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

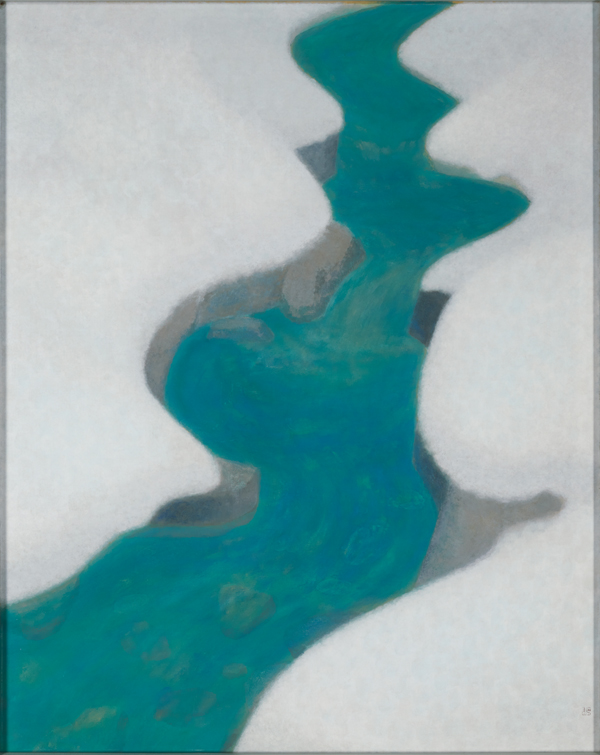

Room 6 Higashiyama Kaii

Higashiyama Kaii was a Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) painter of the same generation as Munakata Shiko, and though five years his junior, he was awarded the Order of Culture in 1969 one year before Munakata received this honor. In this gallery we are pleased to present a total of eight works ranging from 1947, the year of Higashiyama’s art world debut, to the early 1960s when his name became widely known.

In 1947, Higashiyama’s Afterglow was special selected for the 3rd Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition), becoming his de facto debut work. The painting captured the hearts of the Japanese people in the immediate postwar era with both its sincere and realistic rendering and the melancholy that permeated the canvas. In 1950, his painting Road (not exhibited here) reflected the optimism of the time amid hopes of economic recovery. Works such as In the Mountain (1957) and Autumn Colors (1958), for which he traveled to various locations in Japan, aligned with a boom in domestic tourism. His popularity with the general public can be attributed to these works, but also to his cultivation of his personal image through writing, participation in large-scale projects, and collaboration with the mass media, strategies recalling those of Munakata.

Room 7 Beyond Time and Space: The Wood Engravings of Hiwasaki Takao

Wood engraving is a meticulous technique for producing precise and delicate lines by carving into hard boxwood or camellia wood. It was once widely used for book illustrations, but fell out of favor with the advancement of printing technology. However, Hiwasaki Takao, who studied art in Tokyo, returned to his hometown in Kochi Prefecture in 1964 and mastered this technique almost entirely through self-study. From the mid-1960s onward, he devoted himself to wood engraving and revived this technique as a means of artistic expression.

Hiwasaki favored camellia for its softness, resilience, and the warm emotions it evoked. It is said that he polished the wood’s surface with sandpaper, applied black ink, and carved the image directly into the wood without any preliminary drawing, as if he were talking to the rings of the years. There are poetic images of numerous intricate white lines and dots emerging from the pitch-black depths of the background. They seem to beckon viewers into primordial times, or to a world at the outer limits of space-time. In fiscal 2021 the museum received donations of Hiwasaki’s works from his bereaved family and friends, and we are now able to view his works from the early years to the later years. Please enjoy the world of Hiwasaki’s fascinating wood engravings.

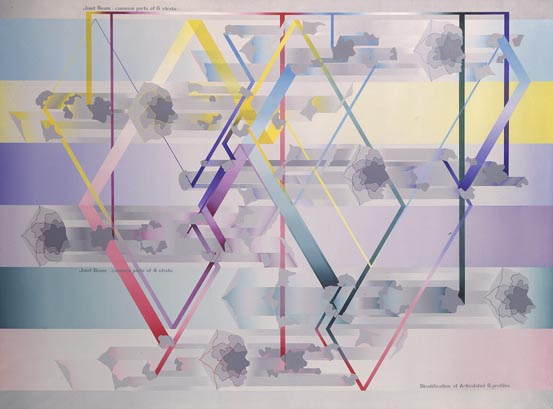

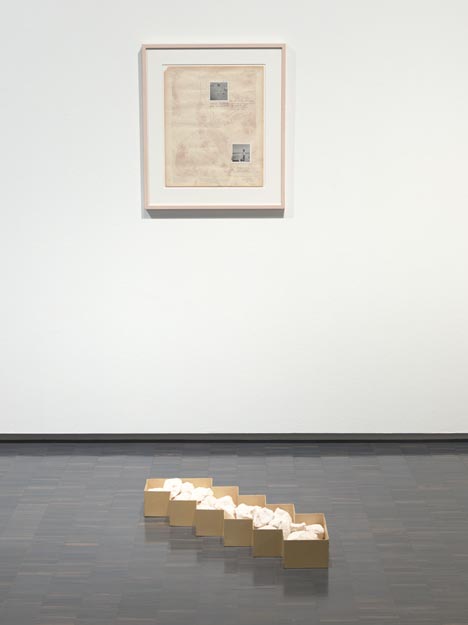

Room 8 Time, Position, Process

In this room, we present works from the 1970s that employ various methods to represent the order found within relationships of time, sound, and objects. This was a time in Japan when the country reached a peak of postwar economic growth, while simultaneously there was a surge in student protests and outcries against worsening pollution and the Vietnam War.

Existing systems and modes of knowledge were being questioned in this chaotic environment, and artists emerged who endeavored to use art as a means of grasping the world around us.

Kawara On rendered the concept of time visible with his Date Paintings. Enokura Koji captured interrelationships between objects in photographs. Tanaka Shintaro illuminated the composition of space through sculptures. Usami Keiji and Kanno Seiko developed painting as a means of conceptually exploring structure, while Nonaka Yuri created collages that established alternative world orders. What these artists shared in common was an approach to seizing the elements of time and space and revealing aspects of their reality. In a time of drastic change, these endeavors can be seen as necessary and inevitable.

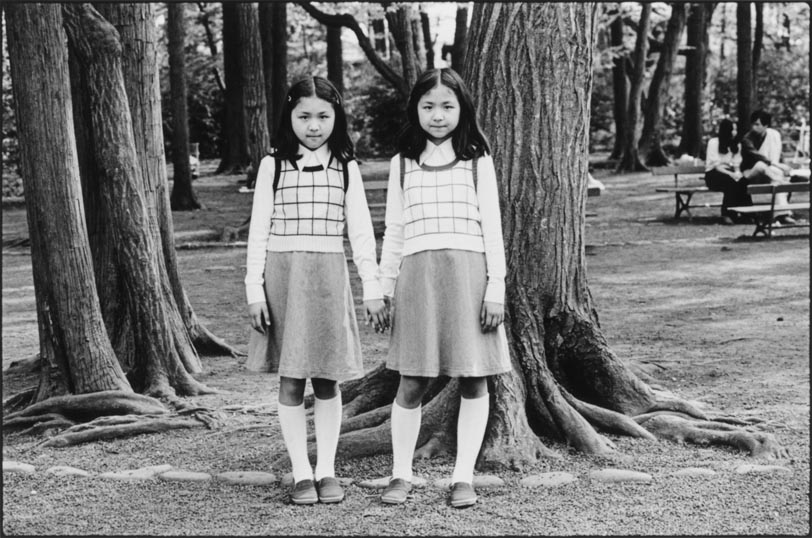

Room 9 Gocho Shigeo Self and Others

Self and Others, Gocho Shigeo’s most notable work, consists of a total of 60 portraits, including pictures of the artist’s family and friends, and children he happened to meet on the street. As the title suggests, the series deals with the subject of the self and others. In this section, we present a selection of 26 works from the series.

The majority of the people in the photographs are staring straight at the camera lens. Their gaze serves as the keynote in the dialogue with “others” in this series. As suggested by Gocho’s use of the title Self and Others, derived from a book by the psychiatrist R.D. Laing, the work is linked to the photographer’s deep interest in psychiatric medicine. Through the gaze cast by the “others,” Gocho objectified the “self,” and attempted to peer into the depths of his own mental state.

Another theme of the series, which features many children, starting with a newborn baby, can be seen as the establishment of the self or the inner maturation of people. This is exemplified by a photograph showing a group of children running into the pale light that appears at the end of the series.

Room 10 100th Anniversary of Taguchi Yoshikuni’s Birth / A Carefree and Light-Hearted Ink Painter

In the area close at hand is a special exhibit on the lacquer artist Taguchi Yoshikuni (1923–98).

He studied lacquerware under Matsuda Gonroku, and learned techniques of Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) from artists including Okumura Togyu. Taguchi lovingly observed subjects such as flowers and insects, and depicted them in innovative compositions with delicate designs. His use of maki-e (sprinkling gold or silver powder on lacquer) and raden (seashell inlay)

techniques earned him high acclaim, and recognition as a Preserver of an Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) for maki-e. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his birth, we are pleased to present some of Taguchi’s finest works along with pieces by other relevant artists.

The area further back showcases Tomioka Tessai (1837–1924), an artist who has enjoyed enduring popularity both during his lifetime and since his passing. In the 1950s he came to be discussed by critics and artists of the day, some of whom referred to him with the nickname “Japan’s Cezanne.” The movement toward reevaluation of traditional literati painting as modern art coincided with growing interest in Munakata Shiko’s woodblock prints during the same period.

Please enjoy this group of Tessai’s light-hearted works, which have been described as “elegant and carefree,” along with those of later artists, remarkable for their sweeping strokes of sumi ink.

Room 11 Imagining / Creating the Body

In this area we present artistic expressions centered on the body, with a focus on Endo Mai × Momose Aya’s Love Condition, which the museum acquired in fiscal 2022.

Please take a moment to let your consciousness permeate your entire body. Are you able to truly feel and experience every part of your body, from your head to your fingers and toes?

The body is the foundation of human identity, yet there are parts of our bodies such as our faces and backs that are hidden from the unaided eye, and it remains an enigmatic entity that is subject to constant change through injuries, illnesses, childbirth, and other experiences.

By focusing on specific parts of the body and at times incorporating elements of their private lives into their works, artists relativize concepts of the body, which we often take for granted, and raise fundamental questions concerning gender, identity, and sexuality. By encountering these perspectives, this has the effect of disrupting and unraveling rigid conventional perceptions and sensibilities regarding the body.

Room 12 Ego and Ecology

Cement Mori, a work by Kazama Sachiko newly acquired by the museum, employs the medium of concrete to encapsulate modern society’s exploitation of nature for human purposes. The work manifests the human ego and desire for control, while at the same time limestone, a key ingredient in cement, has been formed over millions of years through an organic cycle of birth, death, and decay far exceeding the entire span of human history. In this section, we present works from the museum’s collection with a focus on the themes explored in Kazama’s work: the human ego and ecological perspectives. The pieces shown here explore the destruction and pollution of nature by human actions, laborers who have worked tirelessly and often been exploited during the process of modernization, the conflict between environmentally destructive human-made structures and the natural world surrounding and eventually swallowing them, ecological destruction driven by capitalism, the human drive for profound assimilation with nature, and the vast temporal and spatial expanse of nature which surpasses human comprehension. How will the complex intertwining of humanity and nature, ego and ecology, lead us to a path of coexistence in the future?

Hours & Admissions

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

September 20–December 3, 2023

- Closed

-

Mondays (except October 9 and November 27) , October 5 and 10

- Time

-

10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 p.m.)

- Temporarily open on November 27 (10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.)

- Last admission : 30 minutes before closing.

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (¥400)

College and university students ¥250 (¥200)- The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

- Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

- Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

- Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

- Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

- Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Free Admission Day

-

Free on November 3

- Organaized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo