Exhibitions

MOMAT Collection(2024.1.23–4.7)

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

Highlights

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection!

To introduce some features of the museum’s exhibitions of works from the collection: First, its scale is one of the largest in Japan, displaying approximately 200 works each term from the museum’s holdings of over 13,000 works acquired since its opening in 1952. Also, it is one of the foremost exhibitions in Japan, tracing the arc of Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day through a series of 12 rooms, each with its own specific theme.

Some highlights of the current term are as follows. “Takanashi Yutaka: Machi” in Room 9 and “Things As They Are” in Room 11 are exhibits related to the special exhibition Nakahira Takuma: Burn—Overflow, which opens on February 6, 2024. In Room 10, we invite you to immerse yourself in classic works by the dyeing artist Serizawa Keisuke from the collection of the National Crafts Museum. Meanwhile, the “Highlights” section in Room 1 presents an array of practices from our appreciation program, and “In the Artists’ Own Words” in Room 12 features a project utilizing our extensive archive of talks by artists.

We believe our curatorial team has successfully showcased the depth and breadth of the collection and the cumulative outcomes of the museum’s activities. Please enjoy your visit to the fullest!

National Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 18 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as National Important Cultural Properties. These include twelve Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following National Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Kawai Gyokudo, Parting Spring, 1916 | Room1

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection) | Room1

- Wada Sanzo, South Wind, 1907 | Room1

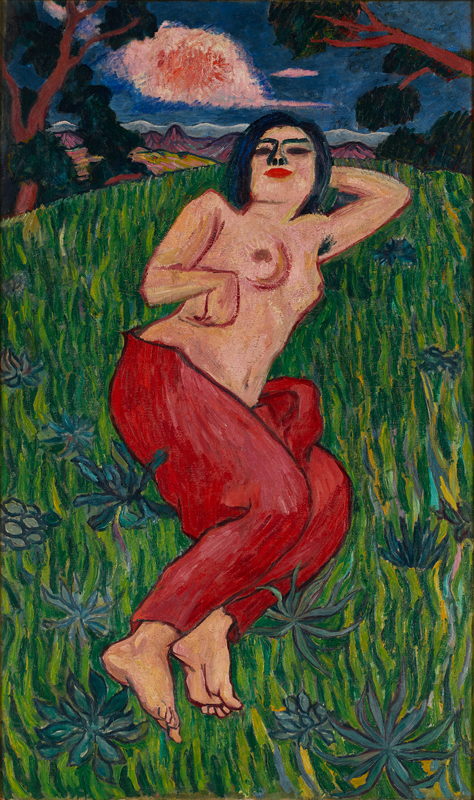

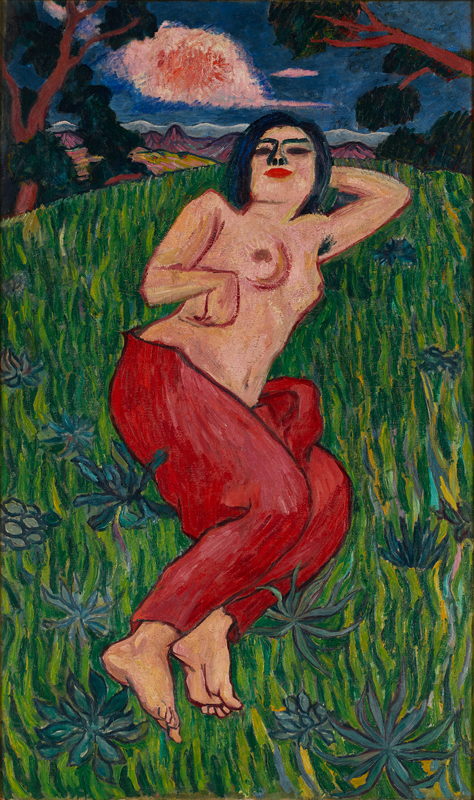

- Yorozu Tetsugoro, Nude Beauty, 1912 | Room2

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915 | Room3

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F(Fourth floor)

Room 1– 5 1880s-1940s

From the Middle of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room 1 Highlights

The MOMAT Collection exhibition of works from our permanent holdings features nearly 200 items in a 3,000-square-meter space. The “Highlights” section of this exhibition features highly prized works of modern and contemporary art that showcase the strengths of our collection.

In the area of Nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) we are pleased to present masterworks that suit the season when we await the arrival of spring. Outside the display cases we feature popular works of modern Japanese Western-style painting, as well as works by Western artists who had a strong influence on the Japanese avant-garde. Among the works shown here are three Important Cultural Properties, including Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring, a scene in which cherry blossom petals flutter down onto a stream.

In addition to the usual commentary on the works, we offer prompts that serve as hints for appreciation. These prompts are chosen based on practices from our appreciation program, in which many people of all ages have participated. Whether this is your first encounter with the MOMAT Collection or you already know it well, please take this opportunity to regard the works from various perspectives and enjoy a relaxed viewing experience at your own pace.

Room 2 New or Old? (January 23- February 25, 2024)

Determining the beginning of something is always a difficult task. The middle “m” in MOMAT stands for “modern.” But when did modern art really start? Half of these works were displayed in the Bunten, an annual exhibition launched by the Ministry of Education in 1907.

Though opinions vary, some have suggested that this event marks the beginning of modern art in Japan.

This was an era in which modern meant “avant-garde.” In other words, the recent past was seen as something old that should be rejected and surmounted. Though the Bunten was initially welcomed, it soon became a stronghold for rigid Academicism and a target of criticism among the younger generation. The rest of these works were made by artists who intentionally veered away from the exhibition.

Do these works, created some 100 years ago, convey the feeling that new things are more magnificent than old ones or vice versa?

Room 2 Spring Festival (February 27-April 7, 2024)

Usually, the works in this room trace the development of modern Japanese art, primarily showcasing works from the 1900s and 1910s. However, this term we have done away with the usual chronological structure and made this room the venue for our annual “Spring Festival” exhibit. Here we present depictions of plants and flowers, and together with two of the paintings in Room 1 — Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring and Kayama Matazo’s Waves in Spring and Autumn — there are a total of eight works through which you can enjoy a spring “flower viewing” experience. By sitting on Seike Kiyoshi’s mobile tatami mats while beholding the broad expanses of Kikuchi Hobun’s Fine Rain on Mt. Yoshino and Hidaka Rieko’s Looking Up the Trees VII, you can savor the Japanese springtime tradition of viewing flowers and greenery while seated on the ground.

As depictions of trees and flowers by Japanese Western-style painters, Tsuji Hisashi’s Camellias and Kids and Saito Toyosaku’s Plum Tree and Tree with White Flowers are rarities within the MOMAT collection. The scarcity of works featuring flowering trees by artists of this genre may result from the fact that, unlike vases of flowers in still life paintings, plants in a natural context lend themselves to a decorative tendency which Western-style painters sought to avoid. These three works are making their MOMAT Spring Festival debut here.

Room 3 110th Anniversary of Reiko’s Birth

Kishida Reiko was born in 1914, the eldest daughter of the painter Kishida Ryusei and his wife Shigeru. Her name is forever inscribed in the annals of modern Japanese art history through Ryusei’s iconic series Portrait of Reiko. One portrait (collection of the Tokyo National Museum) painted when Reiko was seven years old has been designated as a National Important Cultural Property.

Reiko did more than pose as a model. She also began to draw and paint, learning from her father, and as his daughter, model, and student as well, Reiko held a special place in Ryusei’s heart. Although Ryusei died when Reiko was 15, she continued to paint, always keeping her late father’s teachings close to her.

In this room, we present all of the portraits of Reiko in the museum’s collection, as well as a number of Ryusei-related materials from a bequest by his eldest son Tsurunosuke. From fragments of personal life such as photographs, diaries, and postcards, an image emerges of Reiko growing up and the intimate bonds between father and daughter.

Room 4 Modern Actor Prints

Photo: Otani Ichiro

In the early 1920s, Kishida Ryusei frequently took the train from Kugenuma (present-day Fujisawa City, Kanagawa Prefecture) to theaters in Tokyo to watch kabuki performances. His passion for kabuki is clearly evident in his journals, sketchbooks, and albums from the time.

In Room 4, we present shin-hanga (lit “new prints,” woodcuts that revitalized the techniques of ukiyo-e) artists Yamamura Toyonari (Koka) and Natori Shunsen, who depicted modern actors of the era when Ryusei frequented the theater. Under the influence of Western painting and theatrical photography, there was a move towards realistic expression even in actor prints derived from ukiyo-e. Enjoy the contrasting styles of Toyonari, who deftly conveyed the psychology of actors with some exaggeration, and Shunsen, who rendered actors’ features with straightforward beauty.

Hirakushi Denchu’s Study of Head for Kagamijishi [kabuki play], the only sculpture in this room, took the actor Onoe Kikugoro VI as its model, as did the work next to it. After several studies he produced the completed Kagamijishi (collection of MOMAT), which was on permanent view at the National Theatre for a number of years. However, due to the reconstruction of the theater it is on long-term loan to the Ibara City Hirakushi Denchu Art Museum in Okayama Prefecture until the theater’s reopening, and it will be unveiled in February.

Room 5 Intimité

Intimité is a French word that refers to “intimacy, comfort, private life, innermost feelings.” In late 19th-century Paris, a group of painters known as Intimists depicted people in their immediate surroundings, children, and animals, but clearly intimité in art was by no means limited to that time and place. It can be found everywhere from 17th-century Dutch genre paintings to contemporary art. Here, we have brought together Japanese paintings and sculptures that connect to the concept of intimité, dating from the late Taisho (1912–1926) to the mid-Showa (1926–1989) eras: portraits of women by women painters, people absorbed in writing or deeply asleep, miniature fairy-tale worlds, small animals, people cherishing children or animals. And when a solitary figure or animal is placed amid a vast landscape seemingly unrelated to intimité, somehow the scenery suddenly feels more familiar and intimate.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 Art / War: 1941–1945

The Sino-Japanese War began in 1937. The National Mobilization Law was enacted the following year, forcing Japanese citizens to cooperate with the war effort. Artists were no exception. Many were sent to the front and made pictures documenting the war. There was also a crackdown on free and avant-garde expression, leading exhibitions to be banned and art groups dissolved.The works assembled in this room were created between 1941 (the year of the attack on Pearl Harbor) and 1945 (the end of World War II), a period in which war conditions were becoming increasingly severe. The war-record paintings express a direct link between war and art in an easily understandable manner. Other works, which remained firmly grounded in a given style, seem to have largely escaped the influence of the war. Still other works seem to indirectly convey a sense of discomfort regarding the war. It would be inappropriate to divide works of the era into those that represent art and those that represent the war, or those that express support or opposition to the conflict. All of them contain aspects of war and art, and the fact that we are confronted with both of these elements is what makes them so difficult to look at.

Room 7 Presence and Absence: Between the Visible and the Invisible

Hamaguchi Yozo’s prints depicting fruits and vegetables emerging from darkness as if glowing of their own accord have a character in which the familiar and the mystical coexist.

While dating from an earlier time, Kishida Ryusei’s An Apple Exists on Top of a Pot draws the viewer’s attention to the presence of an apple with an unusual composition in which an apple sits atop a pot with no handles. It radiates a singular charm that beckons the viewer to contemplate not only the rendering of the object, but also the weight and wondrousness of the apple itself. When viewing the two works side by side, you may sense a relationship transcending time in which each illuminates the other.

In this room we present works, largely from the 1950 and 1960s, which hover between reality and unreality, oscillating between the visible and the invisible and affecting us not only visually but also psychologically. They include paintings from which human presence is nearly absent, such as Kanayama Yasuki’s Still Life with Irons, Max Ernst’s Momentary Silence, and Yamaguchi Kaoru’s Deserted Small Rhombic Marsh, as well as prints by Hasegawa Kiyoshi, Seimiya Naobumi, and Noda Tetsuya.

Room 8 We Who Distribute

The Distribution Revolution, the title of a bestselling 1962 book by management guru Hayashi Shuji, succinctly conveys the spirit of that decade in Japan, which was marked by the emergence of big-box retailers, the craze for (often sensational) weekly magazines, the widespread adoption of television, and the popularization of terms such as “mass media” and “mass communication.” Over the course of the 1960s, mass production and mass consumption radically transformed Japanese domestic life. The realm of fine art was not untouched by this “revolution,” and pop-culture imagery and mass-produced items that had not been seen as having artistic value began appearing in works of art. This was not necessarily a direct reflection of society, but more of an endeavor to critically interpret a rapidly changing world. Distribution infrastructure underpins our daily lives, but on the other hand it can also be an imprisoning force.

This critical perspective can be seen in works that adopt a strategy of hijacking distribution media themselves, such as printed matter or postal systems. While immersing themselves in the mundane, these artists confronted and battled the proliferating and overflowing imagery pervading society.

Room 9 Takanashi Yutaka, Machi

The place names in titles of works in the Machi series, such as Hongo and Tsukuda, indicate areas at the scale of “neighborhoods.” The artist Takanashi Yutaka notes, “The term ‘neighborhood’ indicates a region slightly larger than a district, and it served me as an important guide for understanding the contours of places.” To viscerally experience the unique character of these places, Takanashi shouldered a large-format camera and equipment and deliberately used public transportation, such as subways and buses, to travel to and photograph each neighborhood.This series is also an endeavor to document things in intricate detail using a large-format 4×5-inch camera mounted on a tripod. Takanashi opted for color film so as to avoid the abstract qualities of black and white, which reduces the colors of the real world to gradations of a single tone. His emphasis on the camera’s basic function of documentation seems to be a response to a 1973 declaration by Nakahira Takuma. A leading figure in the late 1960s in the seminal photography magazine PROVOKE, with which Takanashi was also involved, Nakahira renounced his earlier avant-garde style once described as “are, bure, boke (grainy, blurry, out-of-focus),” and announced that he would adopt an approach to photography which “solely clarifies that things are what they are,” with the illustrated botanical dictionary as a model.

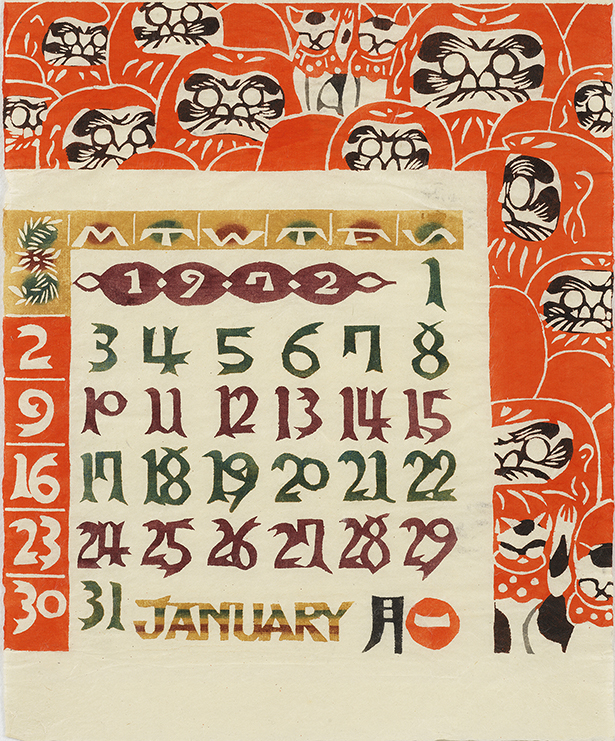

Room 10 New Days with Serizawa Keisuke

Serizawa Keisuke (1895–1984) was a dyeing artist, revered both in Japan and overseas, known for his extraordinary use of traditional katazome (stencil dyeing) techniques to vividly capture the essences of objects. Soon after the end of World War II, Serizawa began producing katazome calendars on washi paper, which brought brightness to the postwar lives of the Japanese people and earned his designs widespread recognition. This work inspired other artists such as Yunoki Samiro to take up dyeing, and Serizawa himself established the Serizawa Keisuke Paper-Dyeing Workshop to mass-produce his works, refreshing his spirit through interactions with younger colleagues who worked there. The National Crafts Museum boasts an abundant collection of Serizawa’s works, notably including the Kaneko Kazushige Collection of over 400 works and related materials generously donated by Mr. Kaneko Kazushige in 2016. This exhibit features not only Serizawa’s works on washi paper, but also the masterworks he created after being designated as a preserver of an Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) for the kataezome (“stenciled picture dyeing”) technique, such as kimono and noren (doorway curtains), as well as works by artists in the dyeing group Moegikai who worked alongside Serizawa. Please enjoy this special MOMAT Collection exhibit, which showcases works from the collection of the National Crafts Museum alongside those from the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

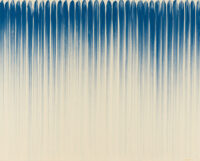

Room 11 Things As They Are

In the 1970s, many artists in Japan focused on presenting phenomena that occurred between materials, engaging in straightforward actions such as simply placing objects in spaces, touching them, or drawing attention to them. This movement emerged from skepticism toward the very act of producing what are conventionally known as “works of art,” and a desire to grasp things as they are without relying on narratives or ideologies. This movement came to be termed Mono-ha (the “School of Things”).

Nakahira Takuma, whose work appears in a solo show on the first floor, declared that he would seek to make photography a tool like an illustrated botanical dictionary, placing him in alignment with Mono-ha (most of the artists featured in this room, including Enokura Koji, Kawara On, Takamatsu Jiro, and Yoshida Katsuro participated in the same international art exhibition as Nakahira). While these artists are grouped with the movement internationally known as Mono-ha, it is intriguing that in their endeavors to produce works that did not resemble conventional art, they did not merely present materials or objects, but frequently toyed with conventions of painting through actions such as crushing, breaking, and piercing.

Room 12 In the Artists’ Own Words

The ability to directly hear artists speaking about their works and creative process is an extraordinary privilege unique to contemporary art by living artists. Since 2005, the museum has been intermittently holding artist talks and filming them, and this fiscal year we have decided to add English subtitles to past talks already available in our art library and release them on our website (the first batch of 21 subtitled talks is scheduled for release in early March 2024). In relation to this, here we present works alongside videos of talks by five artists: Aoki Noe, Kurokawa Hirotake, Kodama Yasue, Nomiyama Gyoji, and Miyamoto Ryuji. Among them, the showcasing of Nomiyama is also a remembrance of the late artist, who had a solo exhibition here in 2003 and died last year at the age of 102.

Words from the artists themselves are profoundly persuasive, and our understanding and experience of the works is frequently changed by these words. In addition to enjoying these precious recordings, we encourage you to thoroughly revisit each work. Also, we invite you to enjoy these artist talks from the comfort of home via our website.

Hours & Admissions

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

January 23—April 7, 2024

- Time

-

10:00 a.m.—5:00 p.m. (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 p.m.)

*Last admission: 30 minutes before closing. - Closed

-

Mondays (except February 12, March 25), February 13

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)- The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

- Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

- Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

- Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

- Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

- Including the admission fee for New Acquisition & Special Display: Germaine Richier, The Ant (Gallery 4).

- Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Organaized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo