Exhibitions

MOMAT Collection (2025.7.15–10.26)

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

Highlights

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection!

To introduce some features of the museum’s exhibitions of works from the collection: First, its scale is one of the largest in Japan, displaying approximately 200 works each term from the museum’s holdings of approximately 14,000 works acquired since its opening in 1952. Also, it is one of the foremost exhibitions in Japan, tracing the arc of Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day through a series of 12 rooms, each with its own specific theme.

All five oil paintings from our collection of 18 nationally designated Important Cultural Properties will be on view together for the first time in many years. Room 3 offers an in-depth examination of one of these works, Kishida Ryusei’s Road Cut through a Hill. Other exhibits focus on themes such as the year 1940 in Room 6, Yamamura Gasho’s series The Children Living in Washington Heights in Room 9, and “Painting and Purpose” in Room 10, all of which relate to this year’s milestone of 80 years since the end of World War II. The current exhibition also features many new acquisitions. As you explore the individual works, we encourage you to note the museum’s recent collecting priorities, including an increased focus on women artists and emphasis on regional diversity. We hope you enjoy this rich lineup of works from the MOMAT Collection, where longtime highlights are joined by fresh new faces.

National Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection contains 18 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as National Important Cultural Properties. These include twelve Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following National Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Room 1 Tsuchida Bakusen, Serving Girl in a Spa, 1918

- Room 1 Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Room 1 Wada Sanzo, South Wind, 1907

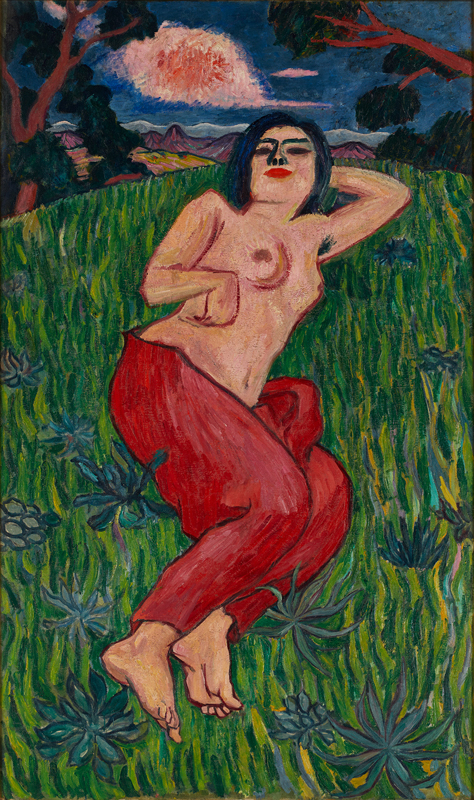

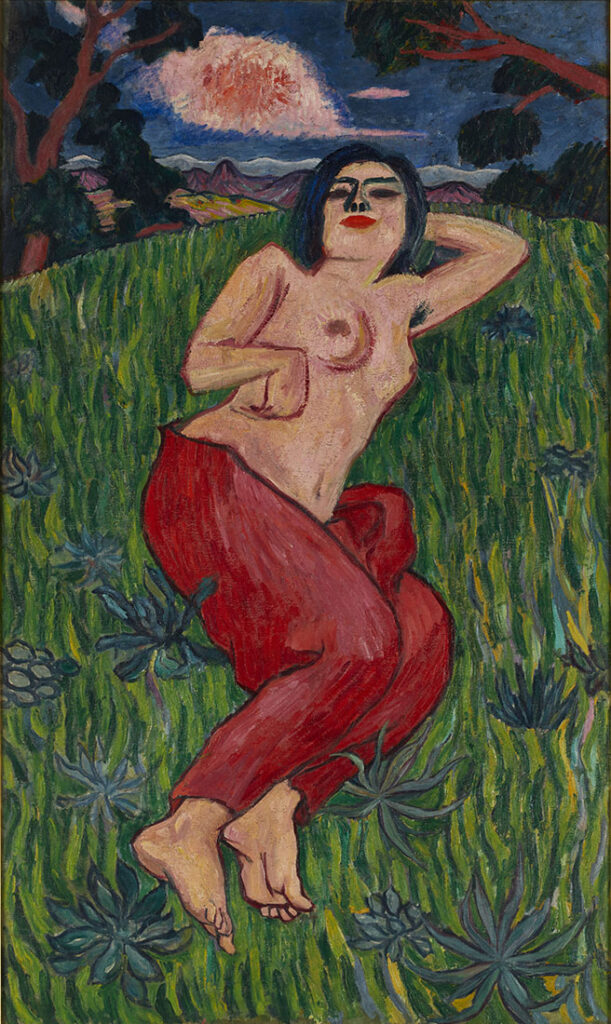

- Room 2 Yorozu Tetsugoro, Nude Beauty, 1912

- Room 2 Nakamura Tsune, Portrait of Vasilii Eroshenko, 1920

- Room 3 Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915

About the Sections

4F (Fourth floor)

A Room With a View

Located on the top floor of the museum, the rest area is furnished with Bertoia chairs, which can be compared to masterpieces of chair design. Please relax by the bright window. The large windows offer panoramic views of the greenery of the Imperial Palace and the Marunouchi skyline.

Information Section

Located in the introductory area, the Information Section presents a chronology of the MOMAT’s history, along with related materials. The materials on display are constantly being changed, so don’t miss them. The section also provides information on exhibitions at other museums that include works on loan from our museum, as well as a system for searching for works in our collection.

Room 1–5 1880s–1940s

From the Middle of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room1 Highlights

The MOMAT Collection exhibition of works from our permanent holdings features nearly 200 items in a 3,000-square-meter space. The “Highlights” section of this exhibition features highly prized works of modern and contemporary art that showcase the strengths of our collection.

The current exhibition is nothing short of spectacular! In the Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) area, the first term (July 15–August 31) includes landmark works such as Serving Girl in a Spa (1918, Important Cultural Property) by Tsuchida Bakusen and Houses in Kyoto, Houses in Nara (1927) by Hayami Gyoshu, while the second term (September 2–October 26) features works such as Indian Corn Plants (1939) by Kobayashi Kokei. Outside the display cases, don’t miss Important Cultural Properties such as Harada Naojiro’s Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon (1890) and Wada Sanzo’s South Wind (1907). Koga Harue’s Sea (1929), a popular favorite that is frequently on loan to museums in Japan and abroad, returns to the MOMAT Collection exhibition for the first time in about two years. Be sure to take note of its dialogue with Max Ernst’s Desert Flower (Desert Rose) (1925), on view nearby. The exhibition also features works by Western artists, including Paul Cézanne, Pierre Bonnard, and Henri Matisse, who profoundly influenced the development of avant-garde art in Japan. We invite you to take your time and savor this lineup of works to the fullest.

Room2 Distinctive Artists of the Taisho Era

In The Bunten and Art, Natsume Soseki’s 1912 review of the official art exhibition sponsored by the Ministry of Education, he wrote that “art both begins and ends with self-expression.” As his words signify, Japanese art during the Taisho era (1912–1926) underwent a major shift in focus, from depicting nature and human subjects as they appeared to the eye to emphasizing individuality and self-expression. Artists who had studied in Europe during the late Meiji era (1868-1912) returned to Japan one after another, and new Western art movements from Impressionism onward were introduced through newly launched art and literary magazines, providing artists with a wellspring of inspiration. For instance, the awkwardly bent female figure in Yorozu Tetsugoro’s Nude Beauty, rendered with vivid colors and forceful brushstrokes, possesses an overwhelming presence that transcends Western influence. Meanwhile, Kishida Ryusei, who made new discoveries while revisiting classical Western painting, sought to imbue realism with a higher spiritual dimension through obsessively detailed rendering. These are examples of how a wide range of individual artistic styles emerged during the period.

Room3 What Was Cut Through by Kishida Ryusei’s Road Cut through a Hill?

One of the highlights of the MOMAT Collection, Kishida Ryusei’s Road Cut through a Hill (a National Important Cultural Property), is distinguished from other paintings of its time by its singular features. These include obsessive realism that harnesses the material qualities of oil paint; the winding road, embankment, and wall receding toward a vanishing point; and the enigmatic slender shadow that cuts across the canvas. However, when it is viewed as just one of many paintings in the collection galleries, its full impact may not be immediately felt. To offer viewers the opportunity to connect with it more deeply, the room has been specially curated with this single painting as its centerpiece. In addition to its striking composition, with the sloping road rising like a mountain in a traditional landscape painting, we invite you to consider Kishida’s efforts to depict a modernizing environment (for instance, how to render a utility pole?), as well as his sense of mystery as embodied by his handling of soil. What was artistically and historically “cut through” by Road Cut through a Hill? Spend some time with this extraordinary work, and discover why it is regarded as a true masterpiece.

Room4 Mountains and Valleys

In the late Meiji era (1868-1912), considered the dawn of modern mountaineering in Japan, mountainous regions such as the Japanese Alps remained an otherworldly realm accessible only to a select few climbers. However, throughout the Taisho (1912-1926) and Showa (1926-1989) eras, improvements in transportation and accommodations gradually opened these areas to the general public. According to Sangaku, the journal of the Japanese Alpine Club, by 1932 the number of mountaineering groups had grown to 264. Regions such as Unzen in Kyushu and Kamikochi in Shinshu had already gained popularity as tourist destinations, with both being selected in 1927 as among the “New Eight Views of Japan” (the eight most picturesque sites in Japan, newly selected for the modern era). The designation of national parks also began in the 1930s. As modern mountaineering took root, the genre of alpine art, which emerged in tandem, also saw rapid growth. By the 1930s, tensions emerged between veteran artists, who had engaged in serious climbing since the Meiji era, and a younger generation of painters, with debates unfolding over how to depict the realities of the mountains. However, from a broader perspective, this marked the arrival of an era in which the public could enjoy a rich variety of artworks portraying mountainous landscapes. How do the mountains and valleys they painted appear to contemporary eyes? We invite you to enjoy this selection of works from the museum’s collection.

Room5 Painting in the 1930s: Between Reality and Illusion

This room primarily features works produced from 1934 onward. Proletarian art (a leftist movement rooted in socialist and communist ideologies), which had been developing since the 1920s, faced frequent government suppression, and 1934 was a year of especially severe crackdowns. From then on, society grew increasingly repressive and the march toward war continued. In the face of harsh and agonizing realities, how did artists respond, and how did they express themselves in the public sphere?

The yearning for antiquity in Yamaguchi Kaoru’s Travel to Ancient Rome (1937) and the surreal worlds depicted in Kitawaki Noboru’s Airport (1937) and Migishi Kotaro’s Butterflies Flying above Clouds (1934) all suggest a desire to escape the here and now. Meanwhile, the piercing gaze of the fish and the bird in Yamashita Kikuji’s Salmon and Owl (1939), and the figure turned away in Fukuzawa Ichiro’s Double Image (1937), do not point beyond the present but instead confront the viewer directly, forcing a keen awareness of one’s own presence before the work. Also note the quiet resistance imbued in works such as Hasegawa Saburo’s Abstraction (1936), in which the artist distances himself from visible reality and embraces the abstract.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s–1960s From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 1940

Three years into the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan was in a state of total war, with every citizen a participant and slogans such as “Luxury is the enemy” widely circulated. The year 1940 also marked the 2,600th anniversary of the enthronement of Emperor Jimmu, regarded as Japan’s first emperor, and commemorative celebrations were held across the country. In the art world as well, events such as the Art Exhibition Celebrating the 2,600th Anniversary of Japan’s Founding were organized and many artists took part. This room features only works that were produced or exhibited in 1940. What kind of impression do these make when viewed as creative expression emerging during wartime? Even works that may, at first glance, appear unrelated to the war are in fact closely connected to the circumstances of the time. For example, the eagle painted by Suda Kunitaro symbolized military aircraft and was associated with prayers for victory. Katsura Yuki’s Work was originally shown with the celebratory title Gasho (“Auspicious Image”). In the context of total war, art, like everyday life, was inevitably expected to contribute to the war effort.

Room7 Women Artists in the Postwar Years

Women in Japan had aspired to pursue art since the Meiji era (1868–1912), and opportunities grew significantly amid the wave of democratization that followed World War II. In the field of education, from 1945 onward, institutions such as the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now Tokyo University of the Arts) and the Kyoto Municipal Specialized School for Painting (now Kyoto City University of Arts) began accepting female students. Around the same time, the Women Artists Association was founded to promote artistic development among women and serve as a springboard for emerging women artists. Led by figures such as Migishi Setsuko, who was among the first artist to hold solo exhibitions soon after the war, the association became a vital forum for many women painters to present their work. More women began exhibiting in government-sponsored exhibitions as well as group shows organized by art associations such as the Nika Association, Dokuritsu Bijutsu Kyokai (Independent Art Association), Shinseisaku Art Society, Zen’ei Bijutsu Kyokai (Avant-Garde Art Association), and the Kofukai Art Association. Some also went on to live and work overseas. Nonetheless, in terms of working environments, exhibition opportunities, and critical reception, gender equality in the arts remained out of reach. This section presents works by women artists who, in the face of various challenges, produced art with unflagging dedication in the immediate postwar years.

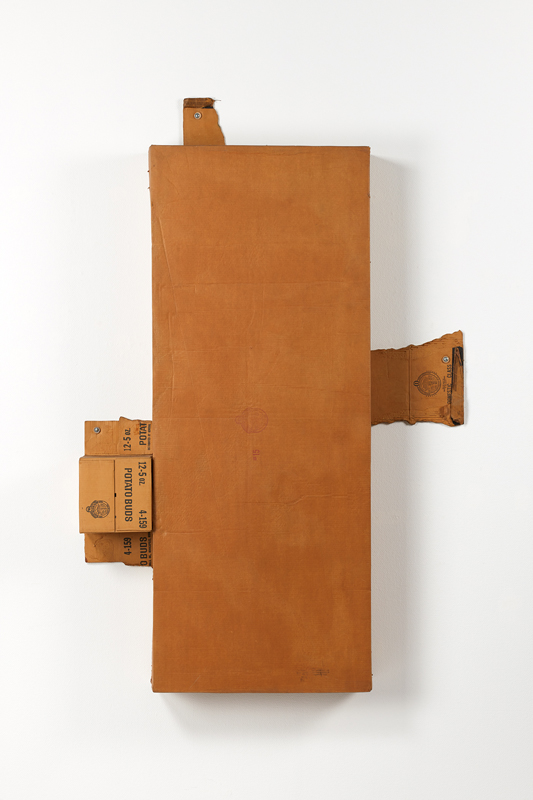

Room8 Junk and Pop

Photo: Otani Ichiro

In the 1960s, as society entered an era of mass production and mass consumption, a wave of art emerged that reflected popular culture through the lens of junk, using readymade products, discarded materials, and rubble that accumulated in people’s everyday surroundings. A major presence in this movement in the US, and one who had a profound impact on the Japanese art world, was Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), who would have turned 100 this year. Known for his Combine Paintings, which combined two-dimensional supports with mundane and discarded objects, Rauschenberg visited Japan several times in 1964 and the 1980s, engaging with Japanese artists and critics. Meanwhile, Kikuhata Mokuma (1935-2020), who would have turned 90 this year, was a key figure in Japan’s “anti-art” movement in the 1960s. He is especially known for his Roulette series, in which he carved the shapes of roulette wheels into wooden supports and sometimes integrated found objects, bringing the format of painting closer to mass culture. Artists who debuted in the 1980s, such as Hibino Katsuhiko, with his cardboard recreations of everyday items, and Ohtake Shinro, who constructs works from a mix of natural and artificial found materials, can also be seen as continuing this legacy.

Room9 Yamamura Gasho, The Children Living in Washington Heights

Washington Heights was a US military facility located on the site of what is now Yoyogi Park in Tokyo. After World War II, the occupying forces took over a former Japanese Army parade ground and built a housing complex for stationed troops and their families. The modern, American-style neighborhood was a world apart, isolated within a city still recovering from the war.

From 1959 to 1962, while attending university, Yamamura Gasho regularly visited the area and photographed children living there. Although Washington Heights was off-limits to Japanese civilians, Yamamura was evidently able to enter the facility with relative ease as a student. In his photographs, Washington Heights appears almost like a world inhabited solely by children, heightening its sense of otherworldliness. Scenes of Halloween, with children in imaginative costumes, draw viewers deeper into this surreal realm. By focusing on children, this work not only captures a distinct facet of postwar society but also evokes a unique atmosphere of multilayered, parallel worlds.

Room 10 Arp’s Studio / Painting and Purpose

Photo: Otani Ichiro

In the area at the front, we present plasters made in the process of sculpting by Jean (Hans) Arp (1886–1966). Born in Strasbourg, France, and active in Paris and Switzerland from the early 20th century onward, Arp is known for sculptures with biomorphic forms occupying a liminal space between abstract and figurative. Here, we trace the evolution of these sculptural forms through the plasters that were a crucial stage in Arp’s exploration of new forms.

In the room beyond, the exhibition reflects on the activities of Japanese painters during wartime. The War Record Paintings in this museum’s collection were commissioned by the military as part of Japan’s mobilization for total war. While oil paintings in this genre by artists such as Fujita Tsuguharu are widely known, 22 of the 153 works in the collection are Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings). Nihonga painters also contributed to the war effort by selling their works and donating the proceeds to the military. While the works range from battlefield scenes to traditional bird-and-flower subjects, all of the paintings on view here are deeply connected to the context of war.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11–12 1970s–2020s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Room11 Shifting Boundaries

This room features works from the collection dating from the 1990s onward, focusing on how political developments and external influences have transformed human activities and landscapes.

Last year, the museum acquired Fences, Okinawa by Ishikawa Mao. Her photographs confront the long-standing issue of US military bases in Okinawa, depicting both local residents whose lives are shaped by this reality and military personnel from diverse backgrounds. Similarly addressing the theme of regional transformation, Shooshie Sulaiman’s paintings trace the complex history of her native Malaysia, depicting the lives of those caught in its shifting tides. Tanaka Koki’s video work documents the process by which differing intentions collide and are negotiated during collaborative efforts. Teruya Yuken presents sculptures that obliquely address the alteration of nature by human economic activity, questioning the relationship between society and the environment. Suzuki Takashi’s photographs foreground ambiguities of meaning that emerge between dual visual planes, drawing attention to how we perceive and interpret the world around us.

These diverse contemporary works invite us to consider what lies beyond the myriad changes that continuously shape our world.

Room12 Horizontal and Vertical Axes

The MOMAT Collection presents works in historical sequence, and in general, each room offers a cross-section of a particular era. While the exhibition of the collection is grounded in a broad survey of modern art history, the specific themes emphasized by individual curators in each room may in fact stand out more. However, because exhibitions are structured chronologically (on a “horizontal” timeline), it can be challenging to showcase the development of artists whose careers span multiple periods (on a “vertical” timeline). In this room, we feature works by Ishiuchi Miyako, Tatsuno Toeko, Mori Bushiro, Yokoo Tadanori, and Lee Ufan, each represented by a selection of older and recent works spanning several decades. Together, they form five small solo exhibitions. The trajectories of these artists vary widely, with some following a consistent path and refining it over time, while others have undergone dramatic transformations at certain points. As you view and compare these works, we invite you to imagine the quests and challenges of each artist. Collecting works from different stages of artists’ careers and tracing their evolution over time is one of the museum’s key roles.

Hours & Admissions

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

July 15–October 26, 2025

- Closed

-

Mondays (except July 21, August 11, September 15, October 13), July 22, August 12, September 16, October 14

- Time

-

10 am–5 pm (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8 pm)

- Last admission: 30 minutes before closing.

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)- The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

- Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

- Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

- Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

- Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

- Including the admission fee for MOMAT Collection Focus(Gallery 4)

- Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5 pm on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Organaized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo