Exhibitions

2021- 3 MOMAT Collection

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

The collection exhibition from March 18 to May 8, 2022

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection! Once again, the time of year approaches when the cherry blossoms of Chidorigafuchi burst beautifully into bloom. To mark this season we are pleased to present masterworks depicting cherry blossoms, including Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring, an Important Cultural Property, in Room 10 on the third floor.

In Rooms 7 and 8 on the third floor, an exhibition entitled White and Black Cartoons focuses on relationships between painting and manga in the 1950s to the 1960s. On view here are painters’ diverse approaches to manga, ranging from social satire to representations of popular culture.

In New Aquisition & Special Display: Pierre Bonnard’s Landscape in Provence, a small-scale exhibit from the collection in Gallery 4 on the second floor, we present Bonnard’s Landscape in Provence (1932), which the museum newly acquired in 2020. The painting, overflowing with vivid color, is being shown for the first time in Japan, and relationships between Bonnard and Japanese modern and contemporary art will be highlighted from several perspectives.

Once again this year, we are pleased to offer an extensive selection of works from the MOMAT Collection for you to enjoy at your leisure.

Translated by Christopher Stephens

Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 15 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as Important Cultural Properties. These include nine Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection)

- Wada Sanzo, South Wind, 1907

- Kawai Gyokudo, Parting Spring, 1916

- Nakamura Tsune, Portrait of Vasilii Eroshenko, 1920

- Please visit the Important Cultural Property section Masterpieces for more information about the pieces.

About the Sections

MOMAT Collection comprises twelve(or thirteen)rooms and two spaces for relaxation on three floors. In addition, sculptures are shown near the terrace on the second floor and in the front yard. The light blue areas in the cross section above make up MOMAT Collection. The space for relaxation “A Room With a View” is on the fourth floor.

The entrance of the collection exhibition MOMAT Collection is on the fourth floor. Please take the elevator or walk up stairs to the fourth floor from the entrance hall on the first floor.

4F (Fourth floor)

Room 1 Highlights * This section presents a consolidation of splendid works from the collection, with a focus on Master Pieces.

Room 2– 5 1900s-1940s

From the End of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

A Room With A View

Reference Corner is currently out of service.

Room 1 Highlights: Focus on Works Acquired in Our First Year

The Highlights section is usually devoted to prominent works from the MOMAT collection, including Important Cultural Properties of Japan, but this edition takes a somewhat different direction. As the museum celebrates its 70th anniversary in December of this year, we are taking this opportunity at the year’s outset to look back on the museum’s beginnings and primarily showcase works acquired in our first year of operation. Of course, among these are masterworks including, in the Nihon-ga(modern Japanese-style painting) category, Tsuchida Bakusen’s Maiko in a Garden (1924), and among Western-style paintings, Yasui Sotaro’s Portrait of Chin-Jung (1934).

Other highlights include Harada Naojiro’s Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon (1890, entrusted by Gokoku-ji Temple, Important Cultural Property), a much-loved presence in our collection; Kawasaki Shoko’s folding screen Buds are Coming-out in Spring (1925), in which female figures are arrayed among various budding flowers, in connection with the Spring Festival in MOMAT held in Room 10; and in connection with the Kaburaki Kiyokata exhibition taking place on the first floor, the works of Kiyokata’s disciples Ito Shinsui and Yamakawa Shuho. Ito’s Portrait of Kaburaki Kiyokata (1951) was in fact painted the year before the museum opened.

Room 2 1907: Before and After

Some may wonder why the work of artists described as the “fathers of modern Japanese Western-style painting,” such as Kuroda Seiki or Asai Chu, are not on permanent display at this museum, even though it is a national museum of modern art. This has to do with the year 1907, when Japan’s first official government-sponsored exhibition, the Bunten (sponsored by the Ministry of Education), was launched. It was regarded as an epochal year for Japanese art, and works were reallocated to (i.e. divided between) the Tokyo National Museum and this museum. As a general rule, works from before 1907 went to the Tokyo National Museum, and those from after 1907 to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (MOMAT). In terms of their role as national institutions, this standard seems to make sense, but a reassessment of acquisition policies is currently underway based on questions such as: Can we really place the origin of Japanese modern art precisely at 1907? Is it possible to revise and update the history of modern art effectively without comparing and examining works from transitional periods, which are difficult to classify as either “pre-modern” or “modern”?

Room 3 Regarding the Self / Regarding the Other

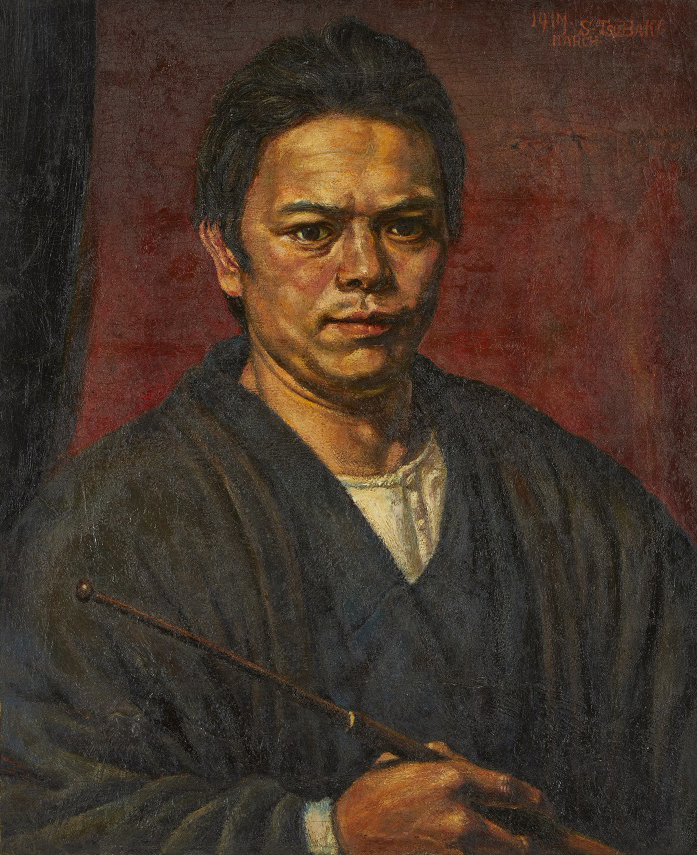

Last year, the museum acquired Tsubaki Sadao’s Self-Portrait with a Mahlstick (1917). Tsubaki was a member of Sodosha (Grass and Soil Society), formed in 1916 with Kishida Ryusei in a leading role, and pursued fine, detailed rendering as a means of penetrating the core of

subjects’ existence. His tendencies are amply illustrated by this self-portrait (a mahlstick is a painter’s tool to steady the hand while working on details).

Around the same time, many painters besides Tsubaki also painted self-portraits. In this room, we present self-portraits by Sodosha painters such as Kishida Ryusei and Kimura Shohachi; by Osawa Seiichiro and Miyawaki Haru, who were non-members but affiliates; by Umehara Ryuzaburo, who studied under Pierre-Auguste Renoir in France; and by Nakamura Tsune, who remained in Japan but greatly admired Renoir and Rembrandt. As symbolically represented in Umehara’s Narcissus, the genre of self-portraiture seems to have encouraged painters to explore the “self,” i.e. the ego, and it is likely that once they had become strongly aware of the self, they were moved to rigorously re-examine relationships between themselves and others.

Ryusei portrayed his own daughter as a kind of sacred being, while Sekine Shoji depicted himself, his sister, and his lover lined up in a row, likening them to the three stars of Orion’s belt.

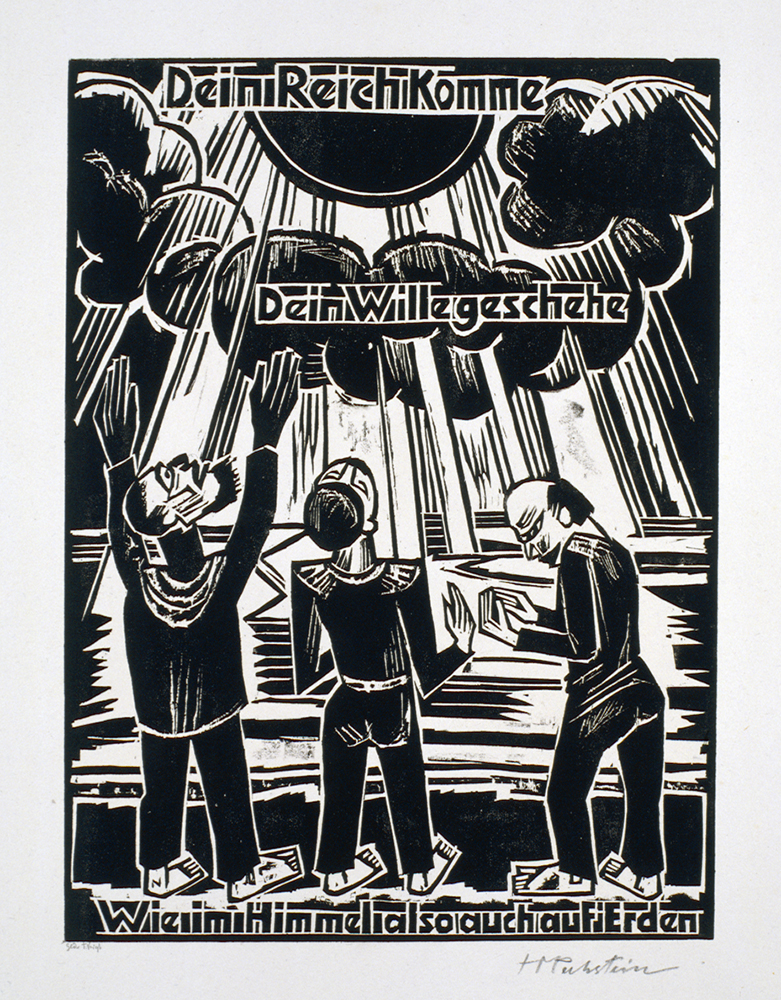

Room 4 Max Pechstein, The Lord’s Prayer, 1921

The painter Max Pechstein was deeply involved in Die Brücke (The Bridge), a group formed in 1905 that played an important role in German Expressionism. The Lord’s Prayer is a portfolio of woodblock prints in which each page illustrates a single line from the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9–13, Luke 11:2–4), which Jesus taught his disciples as a model of the way to pray, with a combination of words and images. It symbolically expresses the pure heart devoted to prayer and the majestic and powerful presence of God, and is a fine example of Pechstein’s style and masterful command of the decorative. He traveled to the western Pacific in 1914 and was inspired by the fantastic scenery of the primeval forest, the vibrant colors, and the rough and rustic atmosphere, which contributed to the robust compositions and strong expressiveness of his works.

His production of prints dealing with religious subjects is profoundly connected to the historical context of the years following World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917. After the experience of postwar devastation, he arrived at a concise and powerful style that differed from his works of the prewar years, which were full of anxiety and anguish reflecting the sense of crisis as the war loomed. While referencing the framework of religious painting traditions, his stylistic transformation makes these works entirely new.

Room 5 Discovering Children

In some respects, the history of modern art is also the history of artists seeking new modes of expression while incorporating various “other cultures.” Children can perhaps be cited as the most familiar source of “cross-cultural” experience for artists, and images of innocence and freedom from social rules and restrictions are often projected onto children. For example, in endeavoring to free themselves from the conventions of traditional art, the Surrealists referenced various methods and motifs including children’s drawings, as well as dreams, the unconscious, graffiti on walls, and even hallucinations. This trend ran parallel to that of recognizing the value of art brut (raw art), with psychiatrists collecting and documenting the drawings of patients as works of art, and the French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901–85) advocating the concept in his 1945 book L’art brut préféré aux arts culturels (Art Brut Preferred to the Cultural Arts).

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s

From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 Nihon-ga and War

During the Sino-Japanese War and World War II in the Pacific, Japanese painters were asked to support the wartime regime in various ways. Perhaps the best-known example is the production of War Record Paintings commissioned by the Army and Navy, but in comparison to oil painting, well suited to representing three-dimensional effects and the depth of shadows, Nihon-ga (modern Japanese-style painting), which tends to be flat and decorative in nature, was not appropriate for the realistic depiction of battle scenes. Under these circumstances, painters such as Yoshioka Kenji and Fukuda Toyoshiro, who were relatively young and had been pursuing new modes of expression in Nihon-ga since before the war, sought ways of depicting the war using traditional Japanese painting materials.

Nihon-ga painters also took part in the war effort by selling their works and donating the proceeds to the military. The museum’s collection contains 184 works exhibited in a show held in 1942 for the purpose of raising funds to build fighter planes, five of which are shown here. Yoshioka, Fukuda, and Yamaguchi Hoshun, who also painted War Record Paintings, here deal with traditional bird-and-flower themes. New Year’s Day, included in the Kaburaki Kiyokata exhibition on the first floor, was also shown at the same exhibition. At first glance it seems to have nothing to do with the war, but if one’s thoughts turn to the historical context, the work takes on a different appearance and significance.

Room 7 White and Black Cartoons (1)

The title of this section is based on the title of a newspaper piece by the art critic Takiguchi Shuzo. Takiguchi described manga (comics or cartoons) in the context of journalism, which were riding the wave of the postwar publishing boom, as “driven by mass demand for distraction,” and termed them “white manga,” meaning that they lacked satirical force.

Meanwhile, he termed painting of the time “black manga.” Painting in those days often addressed themes of society and humanity, and dark, caricature-like expression was on the rise. While conscious of processes by which the genre described as “satire” had been defined and cut off from the mainstream of art history, Takiguchi had high expectations for art’s inherent capacity for social critique, which was emerging amid postwar art trends. With Takiguchi’s perspective, focused on satire and encouraging thought “about the great destiny of painting,” as a guide, in this room we present satirical works primarily from the 1950s.

Room 8 White and Black Cartoons (2)

Kawara On contrasted and sought to transcend two trends that emerged in the 1950s, namely abstract painting, which pursued freedom and universality, and thematic painting, which depicted current affairs in an explanatory manner (“At the Limits of Abstract Painting and Thematic Painting,” Atelier, February 1956). Furthermore, Kawara arrived at an approach that combined mass printing and fantastic iconography, aiming to liberate human consciousness while also participating in society. Many artists of this era, including Kawara, experimented with monochromatic, caricature-like expression, and paintings and manga (comics or cartoons) rapidly came to resemble one another. However, the 1960s saw the rise of highly popular weekly magazines for children consisting mostly of cartoons, and the two media drifted apart again. Unlike the 1950s, when paintings and cartoons adopted similar formats for artistic reasons, in the 1960s many paintings quoted from cartoons that had developed independently and stood as a symbol of popular culture. The reason for paintings being “cartoonish” had changed.

Room 9 Gozu Masao, Harry’s Bar

Harry’s Bar is a series of photographs of a bar on the Bowery in downtown Manhattan.

One summer night, Gozu was on his way home from a photo shoot when he spotted a customer sitting at the window of a bar facing the street, and captured the scene on film.

Afterward, he continued shooting this same view of the bar’s front window from time to time.

In the spot at the window, various men appear in turn, each standing quietly in a pensive manner. The 20-piece series, shot over the course of about five years, is like a group drama with the bar as a stage.

Gozu Masao is an artist who moved to the United States in 1971 and remains based in New York today. Shortly after arriving in the US, he took pictures of residents standing at windows in Chinatown, which led to his Windows series with this subject. Harry’s Bar is another work that focuses on windows and the dramas they frame. He later developed the window motif into a series of three-dimensional works, in which he removed the actual windows of buildings slated for demolition and reassembled them in other locations.

Room 10 Spring Festival in MOMAT

Each year we are pleased to present the Spring Festival in MOMAT. In the space in the rear, visitors can enjoy viewing Kawai Gyokudo’s Parting Spring (Important Cultural Property), Atomi Gyokushi’s Scroll of Cherry Blossoms, Kikuchi Hobun’s Fine Rain on Mt. Yoshino and other seasonal masterworks all at once. Parting Spring depicts Nagatoro, Saitama in spring, with the cherry blossoms along the waterside swiftly scattering in a scene that recalls Chidorigafuchi (another famous cherry blossom site, within walking distance from here). A marvelous variety of cherry blossoms is also on view in Atomi Gyokushi’s Scroll of Cherry Blossoms, with over 40 rare types of cherry trees appearing in its 25 panels, including weeping, yellow-hued, and Izu Oshima cherry trees like those that burst into bloom one after another along the Kinokunizaka Slope on the way from MOMAT toward Chidorigafuchi. Another highlight of this year’s Festival is a rich variety of crafts such as ceramics, lacquerware, bamboo work and textiles. While sitting and relaxing on Kenmochi Isamu’s rattan stools and Seike Kiyoshi’s mobile tatami mats, visitors are invited to bask in the springtime vistas that unfold in these paintings.

In the space in front are exhibited works from the 1990s by artists who work with Nihon-ga (modern Japanese-style painting) materials. There is a particular focus on works that explore relationships between the self and nature, with plum and cherry blossoms as motifs.

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

Gallery 4

New Acquisition & Special Display | Pierre Bonnard, Landscape in Provence

* A space of about 250 square meters. This gallery offers cutting-edge thematic exhibitions from the Museum Collection, and special exhibitions featuring photographs or design.

Room 11 The Shapes of Life

The works presented here are the outcomes of artists’ richly varied efforts to give tangible shape, through a wide range of media, to images of plants, water (or the sea), human beings and their activities, and multifarious fragments of dialogue and interaction among these elements. All of these works delve into relationships between people and the world around them, with plants and water frequently appearing as lodestars for those relationships. What appears may be only a human figure, only a street scene, only a meadow, but through the profound melding of artist and material, the viewer is beckoned on an unexpected journey to another place.

What gives a work the power to transcend the artist’s personal expression and appeal to a wide audience? In addition to depicting people and scenery, a work of art – to put it in slightly lofty terms – has the power to offer glimpses of something vast lurking in the primal wellspring of life itself. This has been the true value of the artistic activity carried out throughout human history, and it remains so today as much as ever.

About the Exhibition

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

March 18–May 8, 2022

- Time

-

10:00 AM–5:00 PM (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 PM)

Extended Opening Hours: 10:00 AM–8:00 PM during April 29–May 8

*Last admission: 30 minutes before closing.

*Kaburaki Kiyokata: A Retro spective opens at 9:30 AM - Closed

-

Mondays except March 21, 28, and May 2; and March 22

- Ticket

-

Online ticket is recommended to avoid lines forming at the entrance.

Online purchase: 【e-tix】

Tickets can be purchased on site at the ticket counters, subject to their availability. - Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (400)

College and university students ¥250 (200)

*The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holder.

*Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

*Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

*Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID. - Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 PM on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Organized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo