Exhibitions

MOMAT Collection(2024.9.3–12.22)

Date

-Location

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

Highlights

Welcome to the MOMAT Collection!

To introduce some features of the museum’s exhibitions of works from the collection: First, its scale is one of the largest in Japan, displaying approximately 200 works each term from the museum’s holdings of over 13,000 works acquired since its opening in 1952. Also, it is one of the foremost exhibitions in Japan, tracing the arc of Japanese modern and contemporary art from the end of the 19th century to the present day through a series of 13 rooms, each with its own specific theme.

This term’s highlights are as follows. In Room 5 on the fourth floor, we present 100 Years of Surrealism, showcasing one of the most significant movements in 20th-century art, Surrealism, including a newly acquired work by Max Ernst on view for the first time. On the third floor Room, in 8, a special exhibit marks the centenary of the birth of Akutagawa (Madokoro) Saori, an artist who soared to prominence in the 1950s. And in Gallery 4 on the second floor, Feminism and the Moving Image explores the works female artists who have been significant figures in video art and the moving image since around 1970.

Once again this term, we are pleased to offer an extensive selection of works from the MOMAT Collection for you to enjoy at your leisure.

Translated by Christopher Stephens

National Important Cultural Properties on display

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Collection (main building) contains 18 items that have been designated by the Japanese government as National Important Cultural Properties. These include twelve Nihon-ga (Japanese-style) paintings, five oil paintings, and one sculpture. (One of the Nihon-ga paintings and one of the oil paintings are on long-term loan to the museum.)

The following National Important Cultural Properties are shown in this period:

- Harada Naojiro, Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon, 1890, Long term loan (Gokokuji Temple Collection) | Room2

- Wada Sanzo, South Wind, 1907 | Room2

- Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill, 1915 | Room3

About the Sections

4F (Fourth floor)

A Room With a View

Located on the top floor of the museum, the rest area is furnished with Bertoia chairs, which can be compared to masterpieces of chair design. Please relax by the bright window. The large windows offer panoramic views of the greenery of the Imperial Palace and the Marunouchi skyline.

Information Section

Located in the introductory area, the Information Section presents a chronology of the MOMAT’s history, along with related materials. The materials on display are constantly being changed, so don’t miss them. The section also provides information on exhibitions at other museums that include works on loan from our museum, as well as a system for searching for works in our collection.

Room 1-5 1880s-1940s

From the Middle of the Meiji Period to the Beginning of the Showa Period

Room 1 Marking Decades Since Models’ Births and Deaths

In this room, we consistently present works of both Eastern and Western art that embody the essence of the museum. This term, we have created a small special exhibit in an area at the rear of the room.

This year marks a number of anniversaries of births and deaths. For instance, it’s the centenary of the birth of film actress Takamine Hideko, who modeled for Umehara Ryuzaburo. It’s also the 60th anniversary of the death of Alma Mahler, who was painted by Oskar Kokoschka. Frank Eugene took photographic portraits of fellow photographer Alfred Stieglitz (on view until November 10), who was born 160 years ago this year. Among the figures in Karasawa Hitoshi’s portrait series, it has been 170 years since the birth of poet Arthur Rimbaud (on view until November 10) and 100 years since the death of novelist Franz Kafka (on view beginning November 12). Eight works, each featuring individuals who reach significant anniversary milestones this year, will be exhibited until November 10, and nine works starting November 12. We invite you to explore and identify the subjects of these works by reading the captions or conducting a quick search on your smartphone.

Room 2 Art of the Meiji Era

In this room, which kicks off a historical overview of works from the collection, we present works produced from the mid-1880s through the early 1910s.

This approximately 30-year period began about 20 years after the end of the Edo Period (1603–1868). These years saw the state of Japanese art change drastically. At the time, many artists sought to bring Japanese art into a new era by combining European standards and homegrown originality in a balanced manner. How should the two be blended? The search for answers plunged them into an all-encompassing process of trial and error. In the results we see the old and the new, confusion of subject matter, mismatch of subject and style, and as-yet-unmastered technique. To present-day viewers who are familiar with subsequent “modern-looking” modern art, their endeavors can be both bizarre and intriguing, but at what point exactly did art begin to be modern-looking? With this question in mind, please enjoy this journey into the formation of modern art in Japan.

Room 3 Land Under Development

After the Meiji Restoration, Japan embarked on a path of rapid modernization, inspired by the grand ideal of “civilization and enlightenment.” The devastating Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 left Tokyo in ruins, but the city’s subsequent reconstruction was extraordinary.

Through extensive land reorganization and infrastructure development, Tokyo was transformed into a modern metropolis. There was a surge in high-rise construction in the city center, and the growth of heavy industry led to the creation of industrial zones along the waterfront. Meanwhile, expansion of the railway network pushed urban boundaries outward and encouraged the building of villas on the outskirts of the urban area.

In Room 3, works by Kishida Ryusei, Sakamoto Hanjiro, and Makino Torao focus on landscapes in the midst of transformation—such as cuttings through hilly terrain in preparation for residential construction, pastures bordered by looming power lines, and sprawling vacant lots. These paintings serve as a gateway to exploring the many facets of modern Tokyo. This was also an era when artists prioritized originality, influenced by the movement known as Taisho Democracy and by Post-Impressionism in art. We invite you to appreciate not only the subject matter of these paintings, but also the diverse styles employed by the artists.

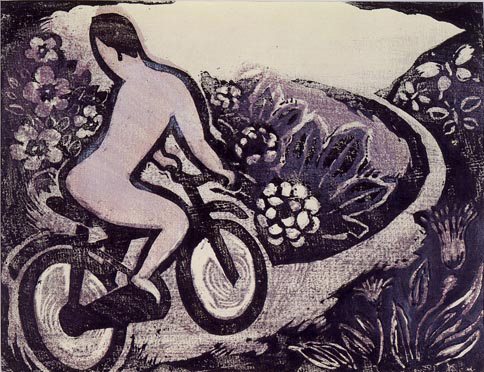

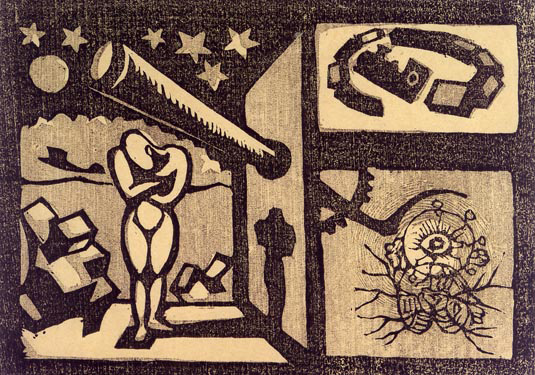

Room 4 Dreams and Freedom: The World of Taninaka Yasunori

Profoundly inspired by Nagase Yoshiro’s Hanga o tsukuru hito e (To Printmakers), published in 1922, Taninaka Yasunori aspired to become a printmaker and began his career in Tokyo, which was being reconstructed at a dizzying pace after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. He exhibited his first woodblock prints in 1926, contributed works to printmaking magazines such as Shiro to kuro (White and Black) and Hangeijutsu (Print Art), and was also active as an illustrator.

Nicknamed “the balloon painter” by the novelist Uchida Hyakken (1889–1971), and known for his eccentric behavior as well as his talent, Taninaka spent his life in poverty, drifting from place to place, and died in Tokyo shortly after World War II.

In Taninaka’s works, modern urban motifs such buildings, airships, and movie projectors coexist with folkloric imagery of dragons, tigers, and demons, creating a fantastical world of contrasting light and shadow that blurs the lines between dreams and reality. Around 1935, as if he was endeavoring to escape the oppressive realities of society, depictions of the external world receded from his work and a utopian world emerged, inhabited by carefree children and frolicking animals.

Taninaka not only stunningly capitalized on the distinctive features of woodblock printing, such as crisp black-and-white contrasts and clear compositions consisting of simplified forms, but also freely incorporated experiments such as printing on thin paper and adding hand coloring.

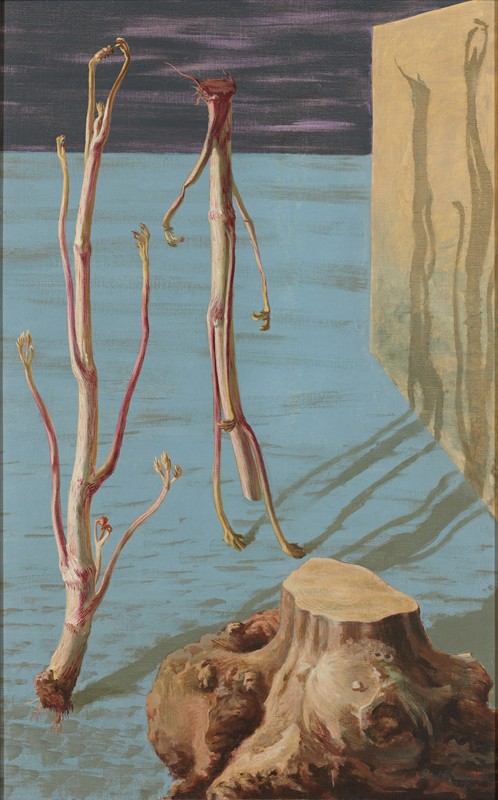

Room 5 Surrealism 100th Anniversary

This year marks the centenary of publication of the Surrealist Manifesto by French poet André Breton (1896–1966). Surrealism, one of the 20th century’s major artistic movements, eschewed rationality and explored the realms of the irrational and the unconscious. With roots in the Dada movement that emerged during World War I, Paris-based Surrealism soared to international prominence and influenced various art forms over the course of many years. In Japan, the Surrealism and its ideas were introduced early on by the critic and poet Takiguchi Shuzo (1903–1979) and the Western-style painter Fukuzawa Ichiro (1898–1992), among others. During World War II, some Surrealists persecuted by the Nazi regime fled to the US, where they continued their activities and impacted postwar American art. This room traces Surrealism’s path and its spread to Japan and the US, beginning with works by prominent Surrealists Max Ernst (1891–1976), Joan Miró (1893–1983), and Yves Tanguy (1900–1955), alongside various historical materials.

3F (Third floor)

Room 6-8 1940s-1960s From the Beginning to the Middle of the Showa Period

Room 9 Photography and Video

Room 10 Nihon-ga (Japanese-style Painting)

Room to Consider the Building (Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing#769)

Room 6 Painting the Other

In war, there is always an “other side.” During wartime, how do people perceive others from enemy nations? During World War II, Japanese artists produced paintings that were intended to bolster war morale and were shown at various exhibitions. In the War Record Paintings housed in this museum, the enemy is often conspicuously absent, and the focus is on valiant depictions of Japanese soldiers in battle. Such portrayals effectively render the suffering and wounded bodies of enemy combatants invisible. However, there are exceptions, and some War Record Paintings depict military personnel from the Allied forces, including the US, the UK, and Australia.

By portraying scenes of the defeat of these “Western powers,” artists sought to affirm the superiority of Japanese forces. Nuances of composition, character portrayal, and color usage in the works in this room reveal the artists’ endeavors to differentiate the two sides. After the war, the Japanese military’s acts of brutality, persecution, and inhumane treatment of prisoners were adjudicated as war crimes at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (also known as the Tokyo Trial) and the Class B and C War Crimes Trial. While aspects of these works undoubtedly appear inappropriate from today’s perspective, we exhibit them to illustrate how Japanese artists during wartime portrayed the military forces of the Allied countries.

Room 7 Playback: Abstract Art Exhibition: Japan and U.S.A. (1955)

Here we revisit Abstract Art Exhibition: Japan and U.S.A., held at the National Museum of Modern Art (then located in Kyobashi, Tokyo) from April 29 to June 12, 1955. This exhibition was set in motion when the group American Abstract Artists (AAA) invited Hasegawa Saburo (1906-1957) to contribute works of Japanese abstract art to their 18th Annual American Abstract Artists exhibition (March 7-28, 1954, Riverside Museum, New York). Hasegawa founded the Japan Abstract Art Club to fulfill this request, and Abstract Art Exhibition: Japan and U.S.A. was a response in kind, presenting abstract works by AAA members in Japan.

Around this time, there were quite a few international exhibitions in Japan. The design of the show at the National Museum of Modern Art, which extended from the first to the third floors, was the work of Tange Kenzo, then an associate professor in the University of Tokyo Faculty of Engineering. The first floor featured Japanese sculpture, the second floor American works, and the third floor Japanese works. This area enables visitors to vicariously experience the exhibition through extant documents and records and a VR reproduction based on these materials.

Room 8 Centenary of the Birth of Akutagawa (Madokoro) Saori

Akutagawa (Madokoro) Saori was one of only a few women who rose to prominence as avant-garde artists in the early 1950s, shortly after World War II. Originally a vocal music student at Tokyo Music School (now Tokyo University of the Arts), she shifted to painting and batik dyeing after abandoning her singing career due to marriage. Akutagawa participated in prestigious exhibitions such as the Nihon Independent Exhibition, the Exhibition of the Modern Art Association, and the Nika Art Exhibition, where she earned acclaim for dye works with themes drawn from Japanese myths and folk tales. In 1958 she went to New York and studied oil painting, and upon returning to Japan, she developed a distinctive abstract oil painting style.

To mark the centenary of the artist’s birth, the museum is exhibiting all of Akutagawa’s works in our collection, alongside those of her contemporaries and related artists. These include Okamoto Taro, who recognized her talent early on and invited her to join the Nika-kai group; members of the avant-garde group Seisakusha Kondankai (Creators’ Roundtable Conference) such as Ikeda Tatsuo, Ishii Shigeo, Kawara On, and Narahara Ikko; Katsura Yuki (Yukiko), a pioneering avant-garde female artist active from the prewar through the postwar period, even earlier than Akutagawa; and Rufino Tamayo, a Mexican painter whose works profoundly impressed Akutagawa.

Room 9 Seino Yoshiko,The Sign of Life (September 3–November 10, 2024)

Seino Yoshiko was an editor at the fashion magazine Marie Claire Japon, then became a photographer in 1995, gaining recognition both in Japan and abroad for her landscape photographs taken with a medium format camera and color negative film.

The Sign of Life is a series compiled into her first photo book in 2002. The images are not of picturesque landscapes or unusual things and phenomena, but rather of mundane scenes from various places in Japan that could just as well be anywhere. Seino pursued not photographs of intrinsically beautiful landscapes, but the beauty of landscapes that is revealed in photographs, difficult to articulate in words and emerging only through visual representation. After carefully gauging composition and lighting so as to capture “signs of life” that appear, she released the shutter is at just the right moment.

The 1990s, when Seino deepened her exploration of photography, was a period when Japanese museums began collecting photographic works, and there was a surge in exhibitions and books showcasing photography. It was also a time when magazines flourished, increasingly focusing on photography-driven content. For historical context, here we also present some of Seino’s early magazine work marking the start of her career as a professional photographer.

Room 9 Seino Yoshiko, a good day, good time (November 12–December 22, 2024)

Seino Yoshiko was an editor at the fashion magazine Marie Claire Japon, then became a photographer in 1995, gaining recognition both in Japan and abroad for her landscape photographs taken with a medium format camera and color negative film.

Her solo exhibition a good day, good time was held in 2008 at two venues, Gallery Trax in Yamanashi and Punctum Photo + Graphix in Tokyo. The exhibition featured photographs of places visited on magazine assignments and in her daily life between 2003 and 2007. In a 2006 magazine interview, Seino described photography’s appeal to her: “There are moments when things and people appear as they are. To put it more poetically, there are times when the night seems more night-like and the wind seems windier than usual. These are the moments I love.”

The 1990s, when Seino deepened her exploration of photography, was a period when Japanese museums began collecting photographic works, and there was a surge in exhibitions and books showcasing photography. It was also a time when magazines flourished, increasingly focusing on photography-driven content. For historical context, here we also present some of Seino’s early magazine work marking the start of her career as a professional photographer.

Room 10 The Spirit of Art Deco/Paintings of History (September 3–November 10, 2024)

In the area at the front of the room, we present works by the French glass artisan René Lalique(1860-1945) alongside those of his Japanese contemporaries. Lalique played a major role at the 1925 Art Deco Exposition. He was in charge of its glass section, and oversaw the design of many pavilions and interiors. Meanwhile, in Japan, metal casters including Takamura Toyochika (1890-1972) and Naito Haruji (1895-1979) spearheaded a movement advocating innovation in craft. Their geometric decorations and highly structured designs reflect the new aesthetic sensibilities of the industrial age.

In the area with display cases in the rear, we present Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings) with mythological and historical themes. These subjects were especially popular in the Meiji era (1868-1912), a time of growing awareness of nationhood, and in the early Showa era (1926-1989) leading up to World War II. Painters diligently gathered archaeological materials, crafted historical costumes and armor, dressed up in these and took photographs to ensure their depictions were historically accurate. Their dedication to studying historical customs appears to have extended far beyond mere patriotic service.

Room 10 The Spirit of Art Deco/All Kinds of Lines (November 12–December 22, 2024)

In the area at the front of the room, we present works by the French glass artisan René Lalique (1860–1945) alongside those of his Japanese contemporaries. Lalique played a major role at the 1925 Art Deco Exposition. He was in charge of its glass section, and oversaw the design of many pavilions and interiors. Meanwhile, in Japan, metal casters including Takamura Toyochika (1890–1972) and Naito Haruji (1895–1979) spearheaded a movement advocating innovation in craft. Their geometric decorations and highly structured designs reflect the new aesthetic sensibilities of the industrial age.

In the rear display case are Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings) featuring various linear styles.

There are soft lines resembling hiragana script (as in the works of Kikkawa Reika) and sharp, wire-like lines (as in the works of Kobayashi Kokei) associated with yamato-e (classical Japanese painting) genre. These crisp “wire-line drawings,” which gained popularity in the 1920s, drew inspiration from sources such as the Kondo Hall of Horyu-ji Temple. Meanwhile, lines that remain aesthetically cohesive despite appearing faded or broken, as in the works of Imamura Shiko and Ishii Rinkyo, can be likened to classical nanga (literati painting), and are described as nanga-style or shin-nanga (neo-nanga).

2F (Second floor)

Room 11-12 1970s-2010s

From the End of the Showa Period to the Present

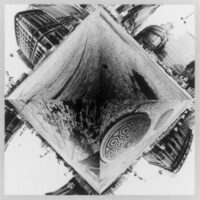

Room 11 Lines and Grid

In 2020, Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #769: A 36-inch (90cm) grid covering the black wall. All two-part combinations using arcs from corners and sides, and straight and not straight lines, systematically. (1994) was installed in Room to Consider the Building in the collection gallery on the third floor.

This term, Room 11 features artists who were LeWitt’s contemporaries and also active in New York, with a focus on the inherent features of lines and grids. In the 1960s and 70s, the art scene was dominated by Conceptual Art and Minimalism, and lines and grids were widely used. Meanwhile, turning our eyes to the city, the grid is a defining feature of New York due to the urban plan known as the Manhattan Grid. Photographs and films shot here reveal correspondences to the actual visage of the city, including the dissonance and darkness that has been a side product of its development.

Room 12 The Essence of Drawing

When you hear “sketching,” you may think of studies and preparatory works for paintings or sculptures. Some may envision art students rendering anatomy or plaster objects.

However, “drawing” can be an independent art form, capitalizing on the distinctive linear quality of the medium.

Historically, sketches have been preliminary steps towards completed works. However, the directness of the artist’s gestures in these work has also been celebrated as compelling art in its own right. From the modern era onward, artists have increasingly explored the kind of impact only achievable through line, and there has been a notable increase in exhibitions recognizing drawings as contemporary art that captures the essence of the present moment. Within this framework, here we present a wide range of drawings employing various media and techniques. Please note the vibrancy and dynamism of the lines, which seem almost to pulsate with life.

Hours & Admissions

- Location

-

Collection Gallery, from the fourth to second floors

- Date

-

September 3—December 22, 2024

- Closed

-

Mondays (except September 16 and 23, October 14, November 4), September 17 and 24, October 15, November 5

- Time

-

10:00 a.m.—5:00 p.m. (Fridays and Saturdays open until 8:00 p.m.)

- Temporarily open on December 16 (10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.)

- Last admission: 30 minutes before closing.

- Admission

-

Adults ¥500 (¥400)

College and university students ¥250 (¥200)- The price in brackets is for the group of 20 persons or more. All prices include tax.

- Free for high school students, under 18, seniors (65 and over), Campus Members, MOMAT passport holders.

- Show your Membership Card of the MOMAT Supporters or the MOMAT Members to get free admission (a MOMAT Members Card admits two persons free).

- Persons with disability and one person accompanying them are admitted free of charge.

- Members of the MOMAT Corporate Partners are admitted free with their staff ID.

- Including the admission fee for Feminism and the Moving Image (Gallery 4)

- Discounts

-

Evening Discount (From 5:00 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays)

Adults ¥300

College and university students ¥150 - Free Admission Day

-

November 3 (Culture Day in Japan)

- Organaized by

-

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo