Watch, Read, Listen

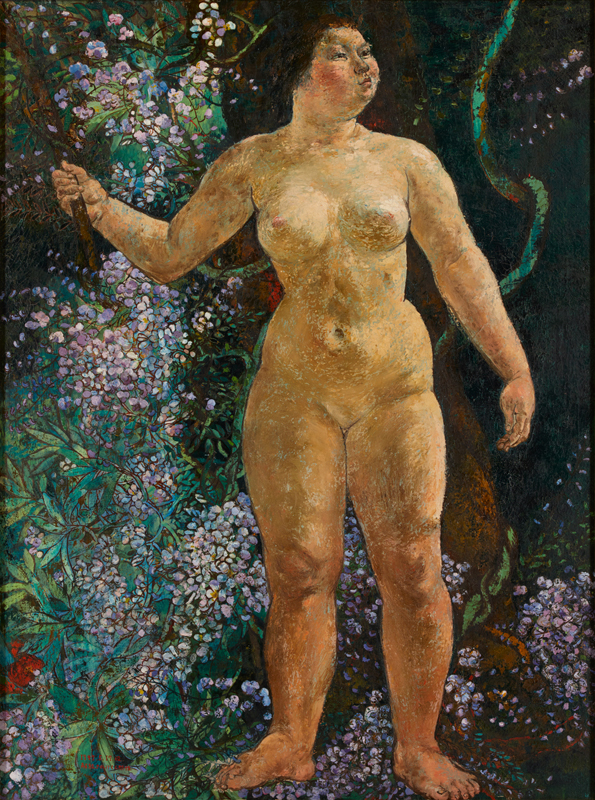

Recent Additions to the Collection MOMAT Collection Newsletter of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo Maruki Toshi (Akamatsu Toshiko), Emancipation of Humanity, 1947

Back

Emancipation of Humanity

1947

Oil on canvas

130.0 × 97.0cm

Purchased FY2018

The title is inscribed in red paint at the bottom left of the painting. In a previous exhibition it was presented with the title Nude (Emancipation of Humanity), but according to the work’s previous owner the word “nude” (rafu, literally “female nude” in Japanese) had been added for organizational purposes. Thus, when it was acquired for the museum’s collection, the title was changed to match the inscription on the painting.

Another inscription reading “1947.5.17.Toshi” is above the title. The first public appearance of this work was at the 1st Avant-Garde Art Exhibition held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum from May 23 to June 7, 1947. Those who saw this painting in Ueno would easily have understood the feelings of the artist, who inscribed the title and exact date on the painting as well as signing it. An event with emancipating effects for humanity had just occurred a few days earlier: on May 3, 1947 the new Constitution of Japan came into effect, calling for popular sovereignty, respect for basic human rights, and pacifism. The artist’s sense of elation at the prospect of living under principles totally different from those of the Meiji Constitution (enacted 1890) seems to have inspired the title, which suggests an ongoing process. To render the sense of liberation visible, Maruki Toshi depicts a figure with gaze directed diagonally upward, nude, and in a space surrounded by flowers, a location that cannot be identified and is thus in a sense abstract.

These features of the painting become more clearly pronounced when it is compared to another of Toshi’s works, Jinmin hiroba (People’s Square) (location unknown), which was shown at the same exhibition. Here “People’s Square” probably refers to the Imperial Palace Plaza in Tokyo. For several years after the war, this plaza was used for various gatherings of the people such as May Day. Toshi seems to have been among the participants in a so-called Food May Day on May 19, 1946, and the figures in her Jinmin hiroba (People’s Square), who are mostly female, may be based on that experience.

If Emancipation of Humanity was painted so as to present a diametric contrast to that scene inspired by real life, then the figure should not be thought of as merely a flesh-and-blood woman. Aspects of a real adult female figure such as pubic hair and nipples are either absent or rendered indistinctly, and the focus is on capturing the body as a volume rather than focusing on such details. The handling of the paint is also notable, especially on the left side of the body, where it resembles the plaster or clay of a statue.

For this embodiment of human beings living under the new constitution, Toshi drew inspiration from sculpture, a medium suited to portrayal of idealized human figures, while placing it in a quasi-abstract space only achievable in painting. This mode of expression enabled her to make a certain statement. By contrast, a look through art magazines of the time shows that female nudes by male painters are less confident and more coy or demure, facing away from the viewer, with cloths wrapped around their waists or legs, or their bodies twisting around. It is clear how fresh and bold Toshi’s work must have appeared.

(Gendai no me, Newsletter of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo No.634)

Release date :